True Detective: Not Seeing Things That Aren’t There

on April 29, 2014 at 0344This is part five of a six-part series about True Detective. Here is the entire essay.

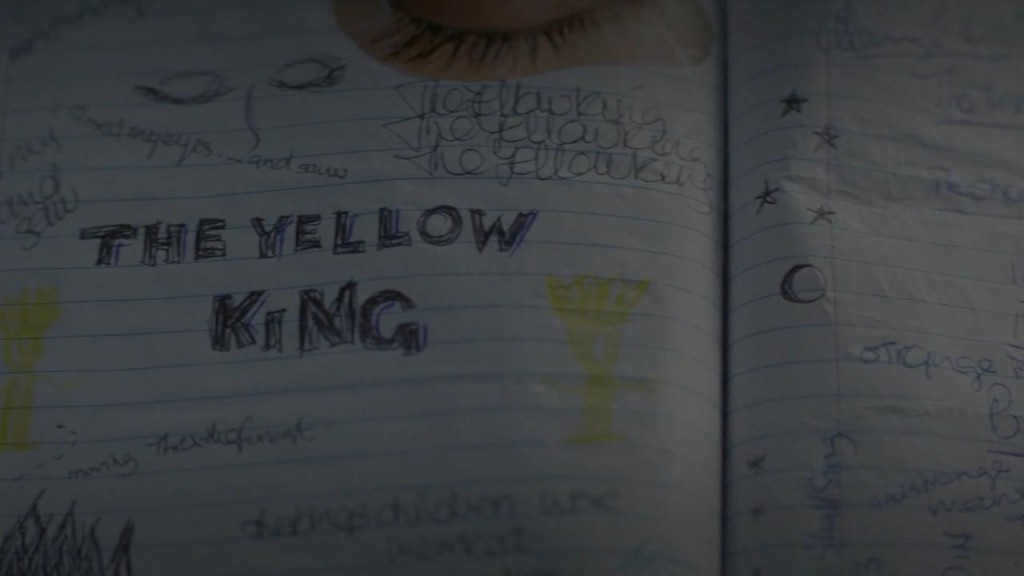

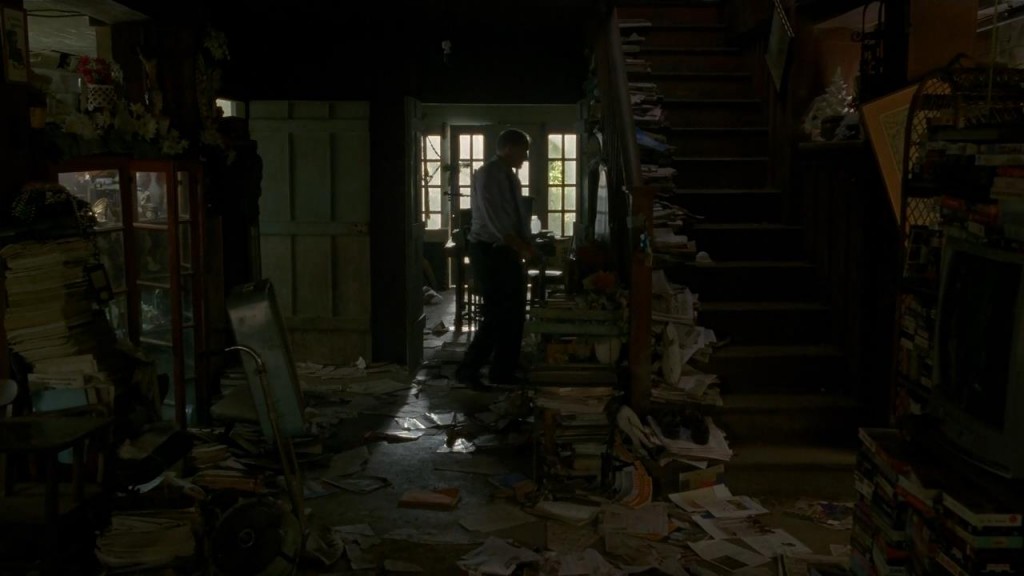

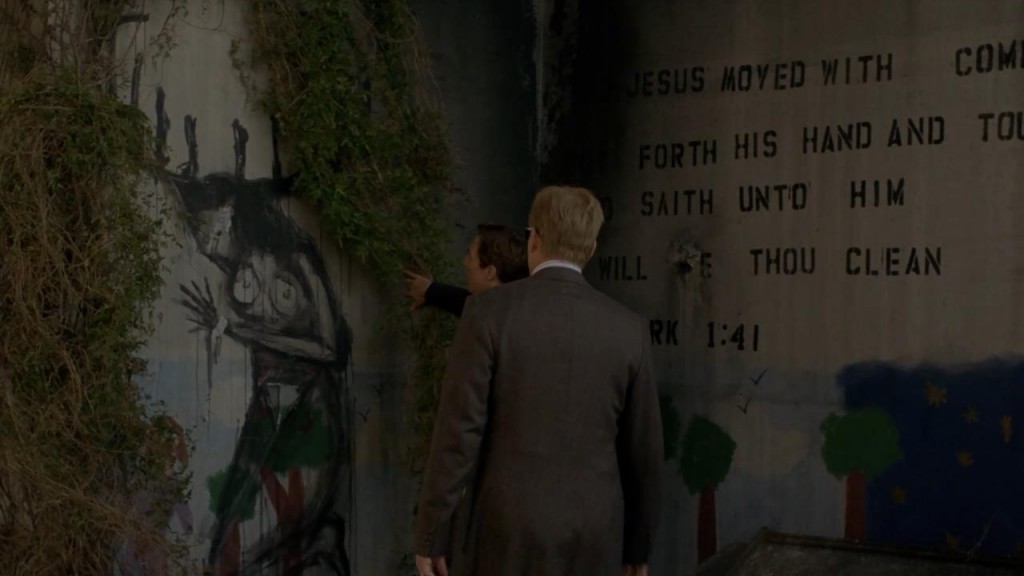

Here is a favorite bit of symbolic visual language from True Detective. When Rust returns to the spooky school at the end of Episode 5, he finds weird paintings and sculptures everywhere. These three things are scrawled on a wall:

Doesn’t get much plainer than that, as set decoration goes.

Now let’s talk about what’s not there.

Hallucinogens

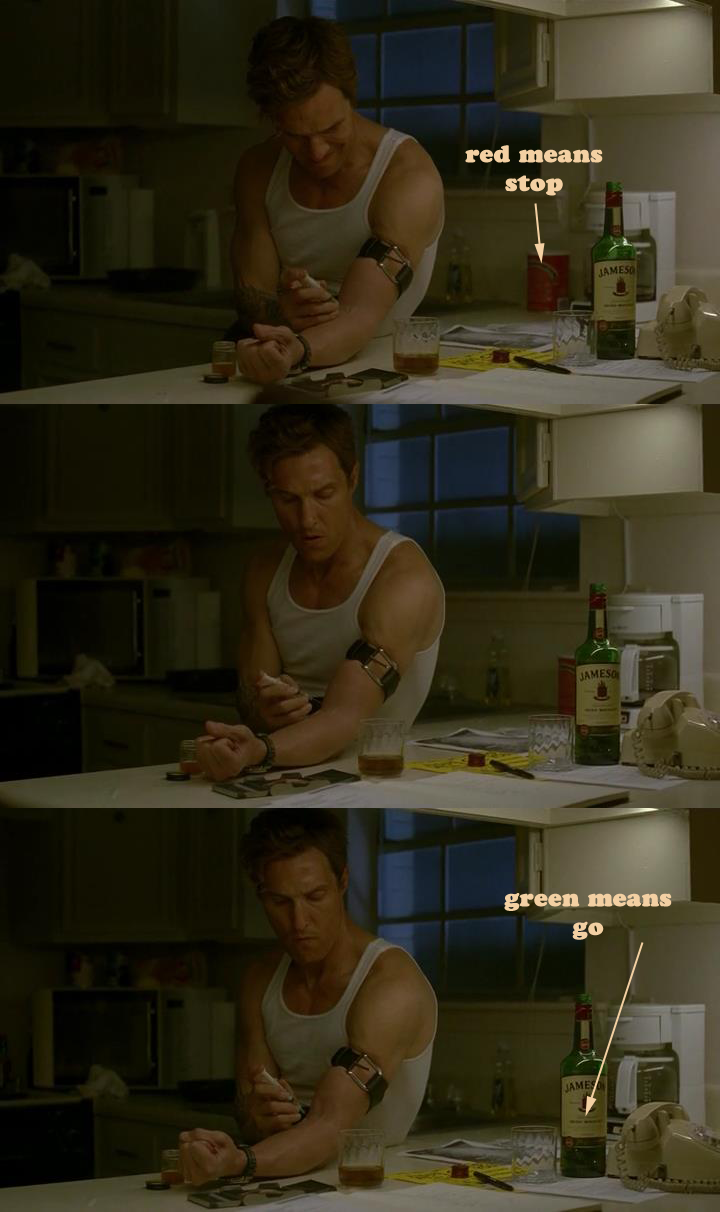

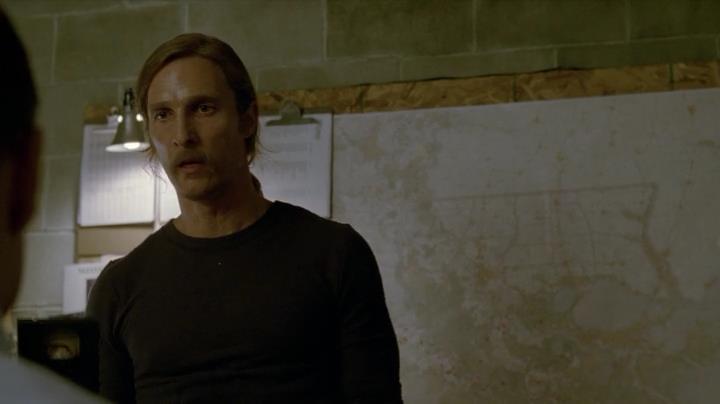

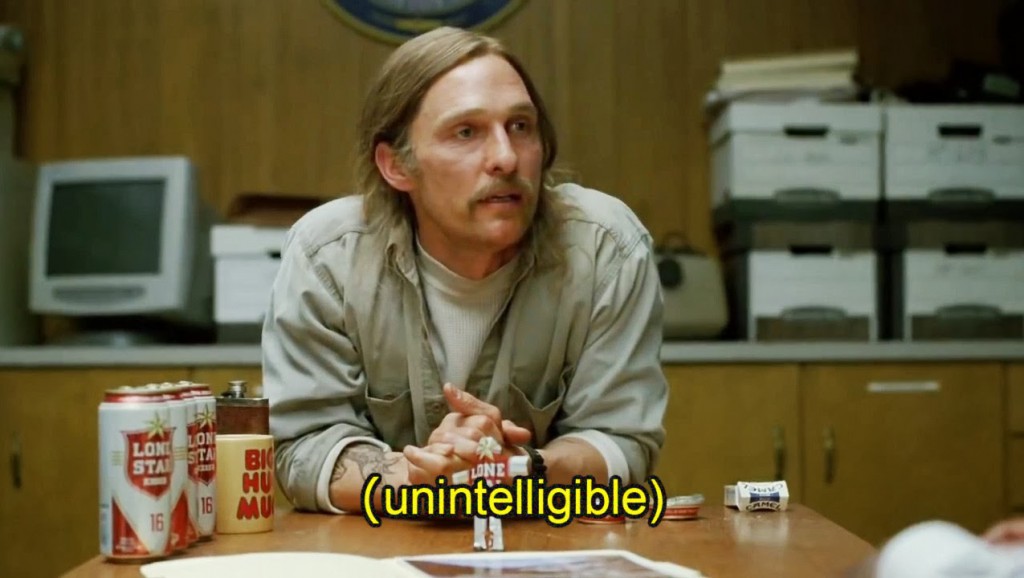

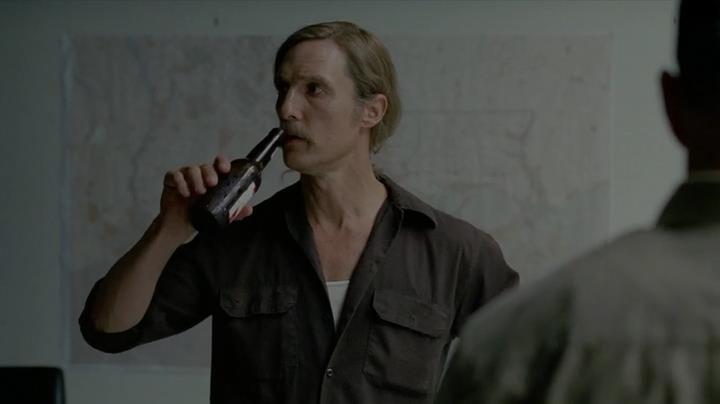

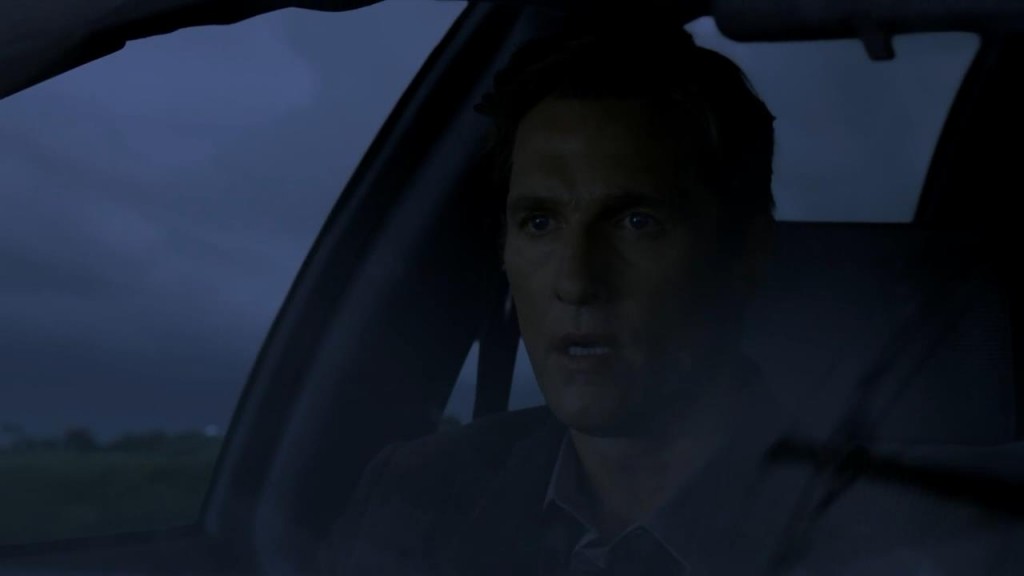

It has come to my attention that there are people out there who have not ever tried hallucinogens. These people may be surprised to hear that this is one of the very few shows in television history that actually gets drugs right, including psychedelics. There are four major CGI hallucinations in the show, and two of them are not anything terribly unusual.

These are called “tracers,” and I believe that it is perfectly safe to operate a motor vehicle while experiencing them.

Again, these two are common experiences. They happen to practically everyone who tries any sort of hallucinogen and they have very basic physiological causes — for example, tracers occur because the irises of the eyes open, the motion of the eyes becomes different, and the way the brain processes the information alters. The streetlights don’t change, but the way you perceive them does.

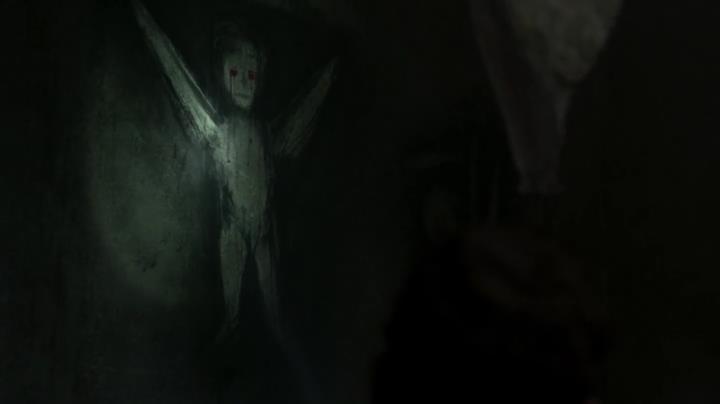

The vortex that Rust sees is quite unusual, true, but it’s also true that when taking extremely heavy shamanic medicines you can see very convincing things for a second, only for them to instantly disappear when you’re distracted (by a bump in a road or a door opening or a giant maniac attacking you with a tomahawk and a knife at the same time).

So let’s dispose of a few things here.

1. Two of the hallucinations are meaningless from the larger story standpoint, they’re there to let you know that Rust has done some hallucinogens (and so have the creators).

2. The spiral is Rust’s brain’s way of letting him know he’s on to something. A particularly beautiful symbol, where all the various birds from the interviews (see later in this article for details on the birds) assemble themselves into a coherent pattern. That is the sort of thing that you could see on hallucinogens, but it would be unusual, cool, and quite memorable. Just like in the show!

3. The vortex was not “really there,” and that’s why Marty didn’t see it. It was probably a “consensual hallucination.”

This is one of my favorite parts of the show, because I’m used to TV getting hallucinogens wrong. But this….this is something that could almost happen.

Maybe Rust, whose eyes are permanently opened to this sort of thing, saw something which many people who have been to this exact spot have also seen. People including the old secretary, Miss Delores:

Miss Delores: “You know Carcosa?”

Cohle: “What is it?”

Miss Delores: “Him who eats time. Him robes. . . It’s a wind of invisible voices.”

Dora Lange probably saw it:

Reggie LeDoux probably saw it:

Reggie: “I know what happens next. I saw you in my dream.

You’re in Carcosa now. With me. He sees you.”

Let’s wonder if what Rust saw is what they saw:

It’s not “really” there. It disappears the second he’s distracted. But maybe it is “really” there, in that other people have seen it, over a large amount of time. I’m reminded of Grant Morrison’s excellent book Supergods, where he points out that yes, Superman and Batman are not real. But in another sense, they’re actually more real than he is. More people know them. More people care about them. They’re older. They have specific life histories, specific personalities, specific modus operandi. They will still be around long after Grant Morrison and everybody who ever knew him are crumbled to dust. In some ways, they are actually more real than their creators.

Maybe the vortex is “there” in a consistent fictional sense — as a tulpa, or a ghost, or a something, or whatever you want to call it. The point is that many people have seen it and not known what they have seen.

This is about religious experience. Even if you’ve never seen God, you know that people have. They may not have in the scientific and rational sense, but in a real and memorable way that is real to them. And the same goes for Zeus and Thor and UFOs — they may not be “real,” but we know that people have seen them as if they were. Maybe behind our little stories is the occasional true fiction. Maybe our myths are shadows cast by something that stands outside of our perception. A lot of people would say “other dimensions.” I don’t believe in other dimensions, so I hate to go there, but you could sure call it that.

Maybe the vortex is a personal “god” that has been seen by many hallucinogen-addled people (and hallucinogens are far, far older than LSD) who have been in that particular room worshiping at that particular altar in a wide variety of emotional states, and many have died in that room too. Whatever energy there is in the human mind and human heart has been repeatedly harvested to feed/create/make contact with that thing, and even if it’s not real enough for Marty to see it’s real enough for Rust to see.

But it’s not “really” there. It’s a hallucination, maybe shared, maybe not.

Let’s talk about other things that may or may not be there.

Spirals

Spirals are everywhere in this show, and I mean everywhere.

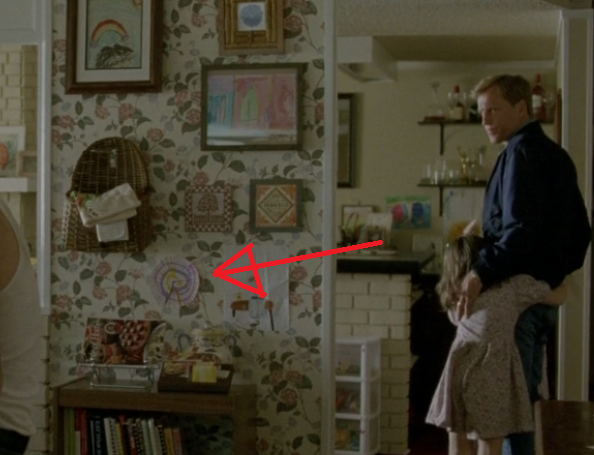

You see that spiral on the wall of Marty’s home? HE DIDN’T EVEN KNOW IT WAS THERE.

Neither did the writer, director, or set designer. They just got a bunch of kids’ drawings and put them on the wall, and it just so happens that one of them was a spiral? Why?

BECAUSE SPIRALS LOOK COOL AND LOTS OF PEOPLE DRAW THEM.

It’s a basic human symbol. Here’s how you draw a spiral: try to draw a circle, fuck it up, but keep going. Pretty easy!

Look, he’s mowing the lawn in an expert lawn spiral! He is not mowing the lawn in a spiral to show cult involvement, he’s mowing it in a spiral because that’s the most efficient way to mow a lawn, and that’s why they showed him mowing the lawn — because it fit in. They didn’t invent a new way of mowing lawns for True Detective. Rather, they used what was around that fit, and the better it fit the more they emphasized it. It’s a small but important distinction.

So spirals are everywhere, but they are not always a sign of cult involvement. They’re a shared idea that everybody working on the series had incorporated at several points in several ways. They’re not a clue, they’re not even a clew.* They’re a motif. They don’t point to anything** specific except the process by which the director and production crew made the movie. Never forget that, long before you get to see a TV show, it is a story that the creators tell to each other. When you remember that it helps to separate the things that are meaningful from the things that are, for lack of a better term, set dressing. You have to be able to separate the two. If you don’t, that way conspiracy theory lies, and that’s almost as bad as being blind. Seeing too much can be as distracting as seeing too little when what you actually want to do is to see the truth.

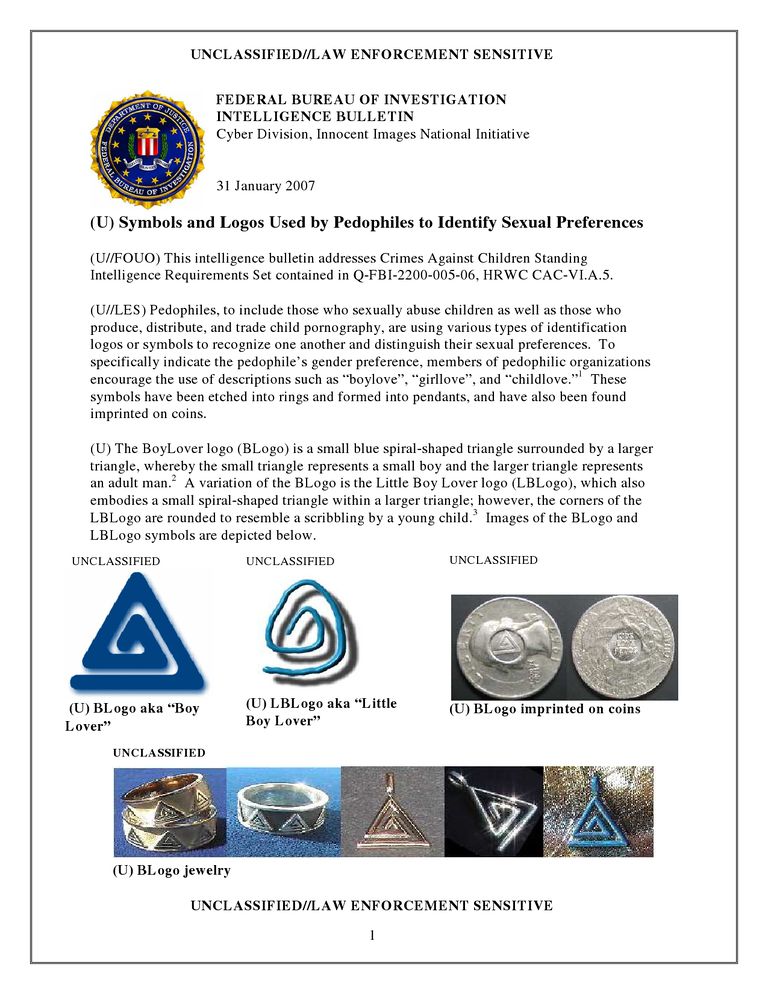

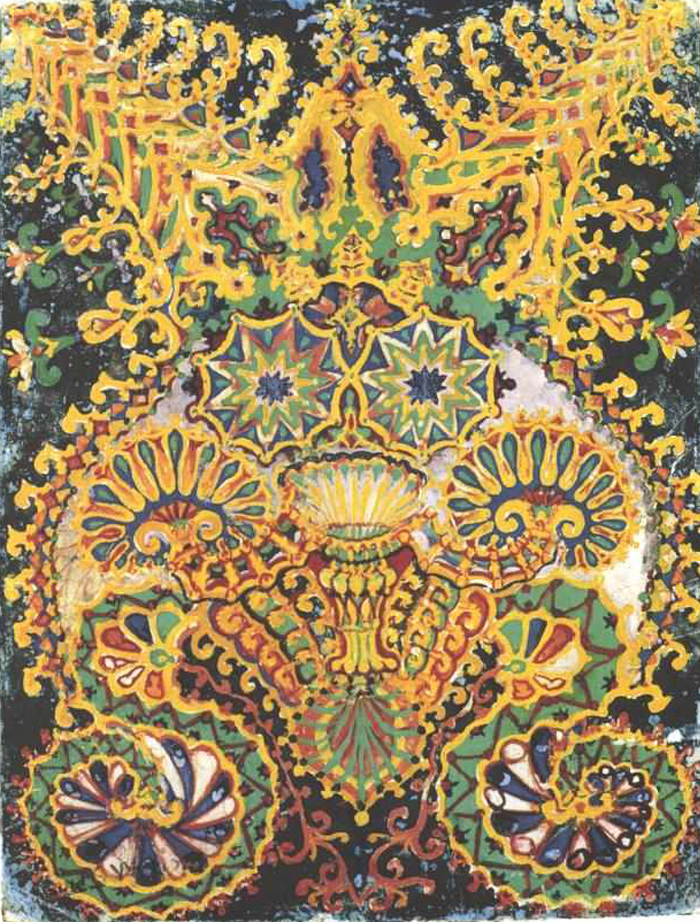

Here’s my favorite spiral:

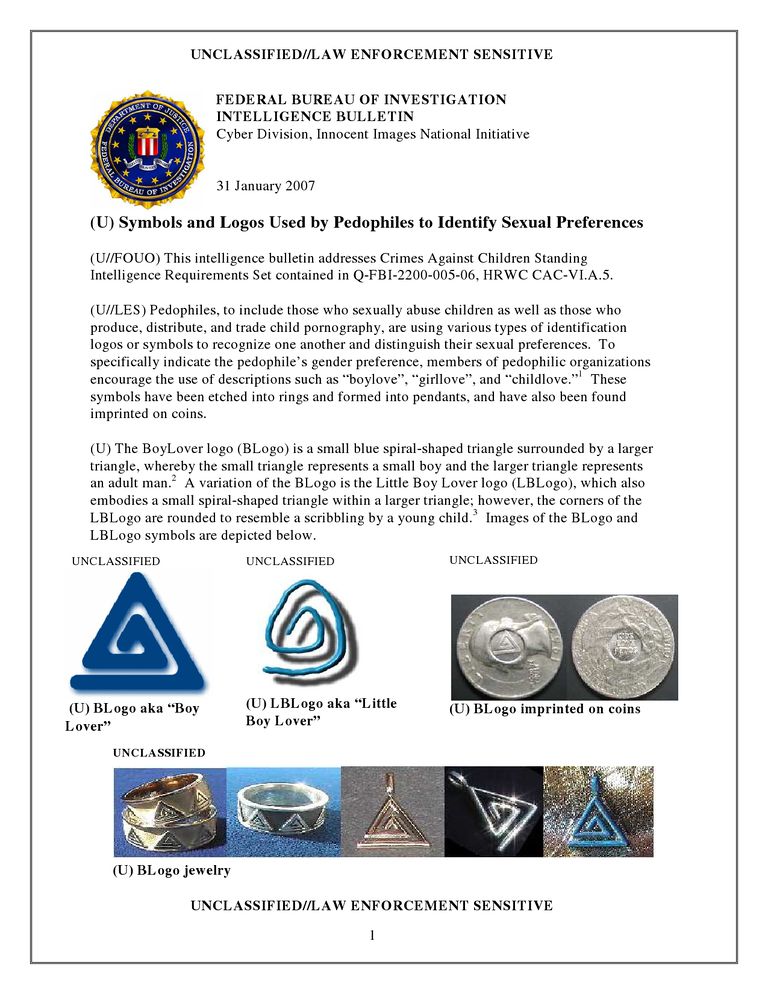

This is from Wikileaks, and it is from 2007.

And let me just say how perfectly multifariously creepy it is that pedos call their nightmarish film company “Innocent Images.”

That’s horrible on at least three levels.

Look at the date. 2007. Look at the source; this is from the FBI by way of Wikileaks. This is real; this is a real thing done by real people in the real world, god help us all. Obviously Pizzolatto and Fukunaga did not invent this for this show. But I do wonder if they were aware of it. And either way you look at it, I thank them for bringing this to our attention.

Once again, it is the difference between inventing things, which is a bad way to do things, and using things you find lying around, which is a good way to do things. It’s bad to invent these things, because the human mind is quite limited compared to the totality of society and the things we make up always seem paltry and frail compared to the robustness of real life — read any high fantasy novel for a perfectly stultifying demonstration. It’s good to use things, because that attaches your story to real life, makes things bigger than they ever were. Instead of a pathetic ivory tower, your story is a bustling marketplace, where all are free to trade.

*I’ve been waiting to make that joke for about fifteen years, by the way.

**of course not, they’re spirals.

Patterns

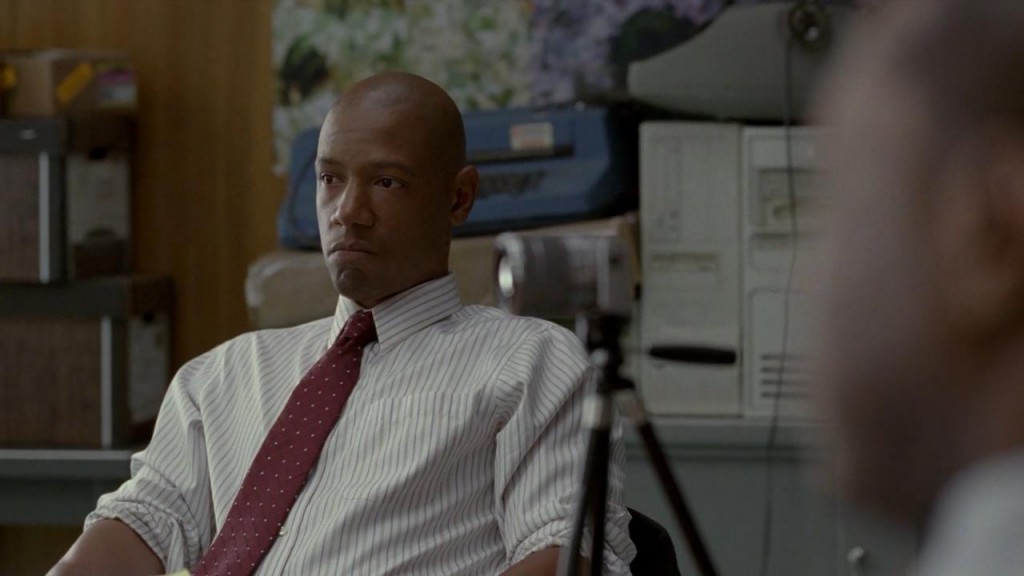

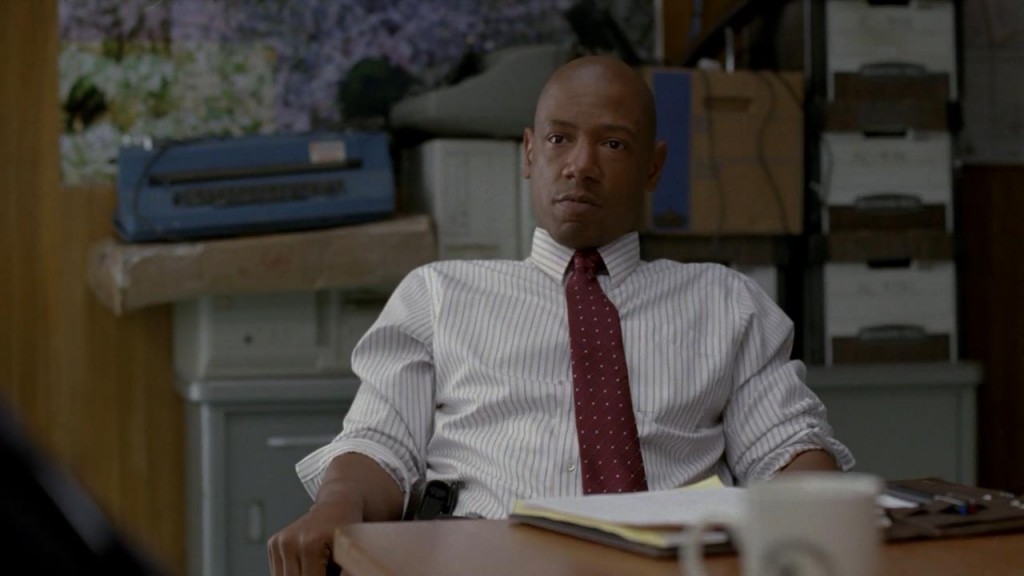

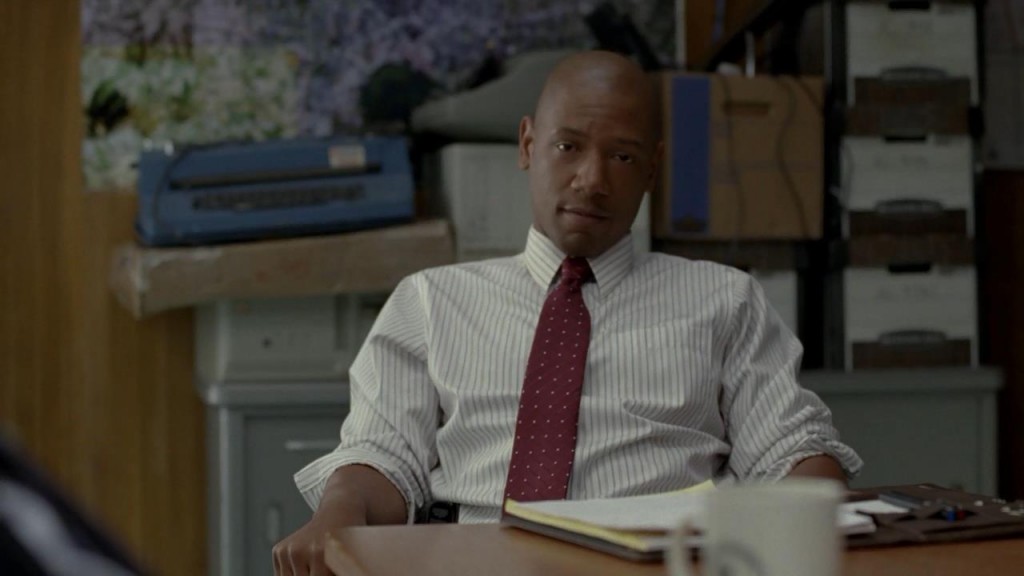

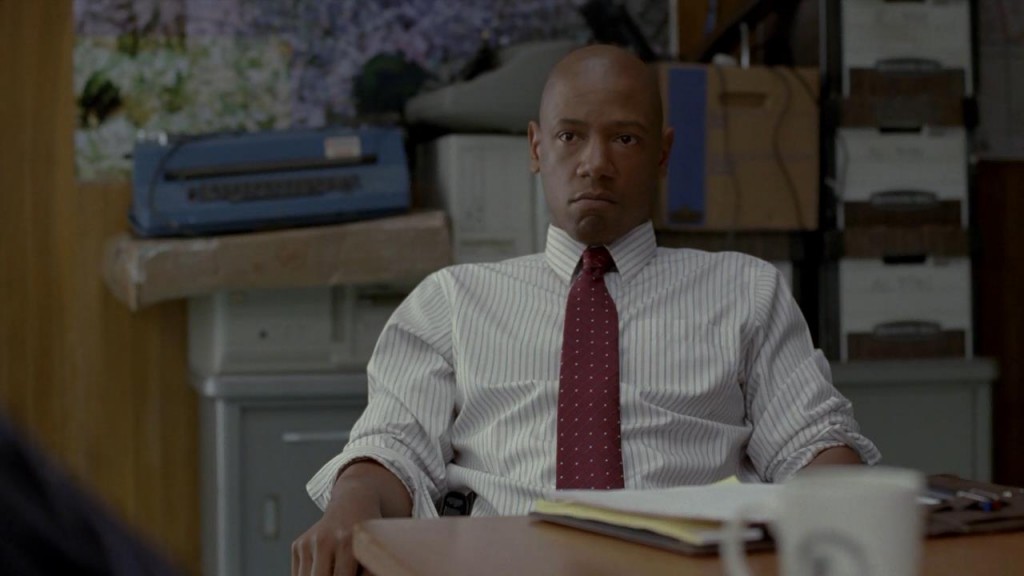

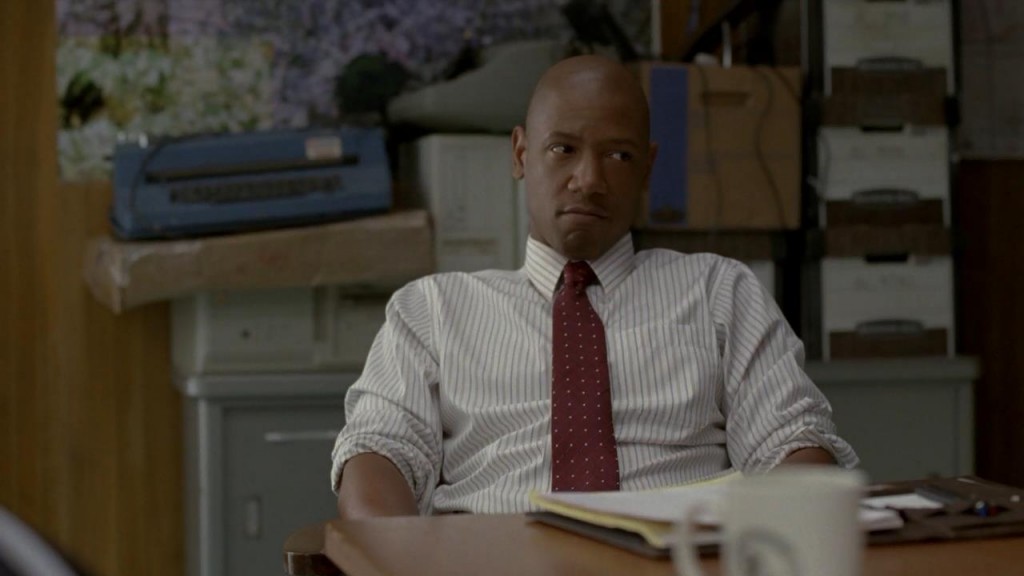

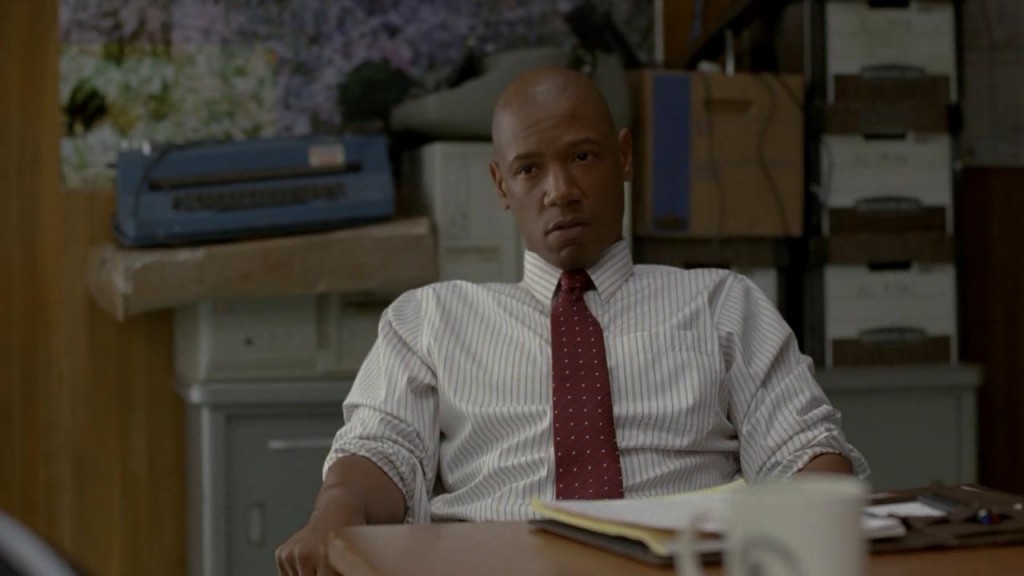

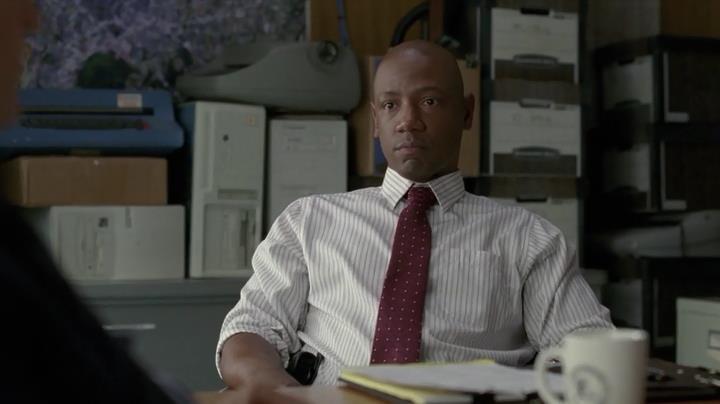

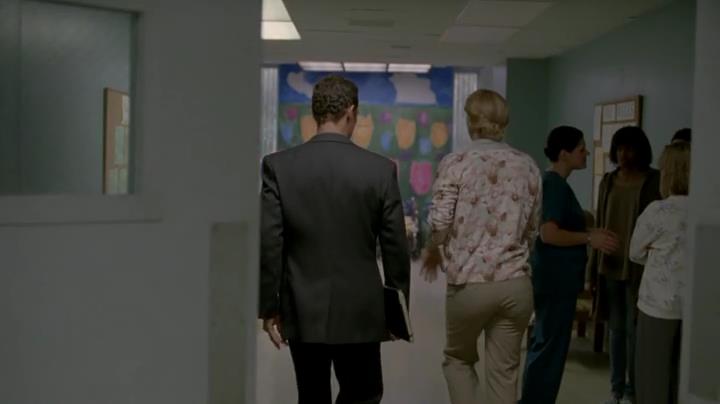

In this show men wear strong solid colors or, if they’re feeling frisky, plaid. Women wear patterns, especially floral patterns. This is because the show happens in a world where men believe themselves to be solid, staid, predictable men (even as they drink, screw, buy drugs, cheat, drive drunk, beat up people who are dating their ex-girlfriends, beat up people who date their daughter, and generally commit pure havoc) and they believe women to be mysterious creatures with strange color schemes.

You could call this sexist, for all the good it’ll do you. The point here is that it’s true. It’s true for the show, and it’s true for a lot of people who watch the show. This really is the way that manly-type men that you see on TV see the world and the people in it. It’s sexism in the same way that a doctor is the disease that they treat; sort of, but not really.

In real life women are people. But that is too complicated for this show and many of the men who watch it. In this show (and to many of the people who enjoyed the hell out of this show) men wear solid colors, navigate by patches of solid color. Women are complex, confusing, blending into the background, difficult to describe.

In this case the show presents both the doctor and the disease. Make of that what you will. It does this quite often. The binary pairing of ideas is actually one of the fundamental motifs of the series, and I challenge you to notice how many times two people are compared to each other, two ideas are compared to each other, or the screen is divided between two contrasting visual elements.

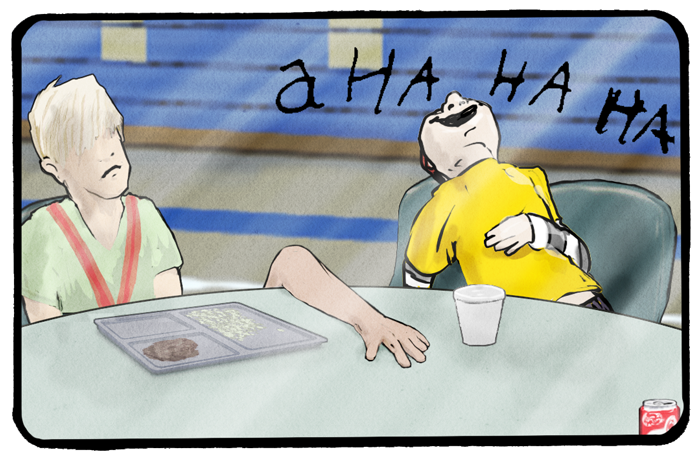

Whenever I look at this shot I think of that scene in “Babe” where the pig separates the brown chickens from the white chickens.

Let’s just agree that, by this point, we’ve established that certain things are there, certain things are not there, and we can sort-of tell the difference.

In and Out of the Crosshairs

I borrowed this from my wife, Gewel Kafka:

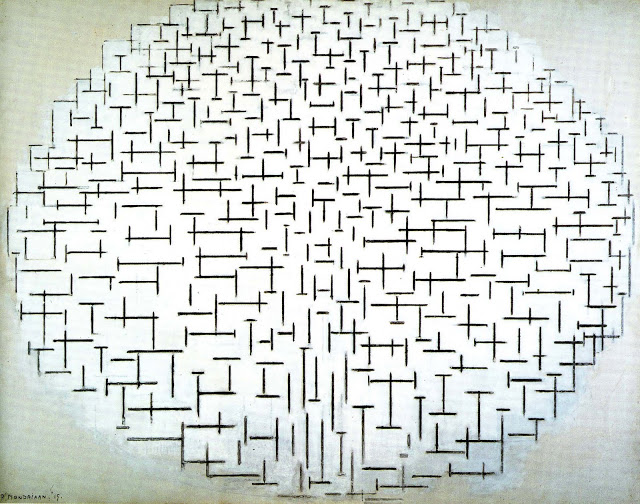

Piet Mondrian’s used of vertical and horzontal lines was adapted after his visit to Paris in 1912 where he saw the work of the inventers of cubism, George Braque and Pablo Picasso. Over the next few years Mondrian would refine this grid that he borrowed form their work, simplifing his subject matter to its skeletal minimum: Verticle and horizontal lines. Unlike his cubists contemporaries that nearly saw the cubist grid as a means to portray the ether of reality by showing the transparencies of substructure, whether a line was horizontal or vertical, a plus or a minus, determined whether it was static low energy, or a dynamic high, and this held deep spiritual meaning, so that the act of composing a painting was a process of balancing the universe.

When she told me that, it was the first time that I really “got” Mondrian. It’s so simple and it’s so deep. Horizontals and verticals are fundamentally different. A vertical is a thumb in the eye of entropy, a horizontal is the natural state of mud. Verticals represent effort, activity, motion. There is no such thing as a cross, a perpendicular, a plus sign in nature. They are all products of our mind. But that doesn’t make them any less true. Here’s Mondrian’s painting “Pier and Ocean.”

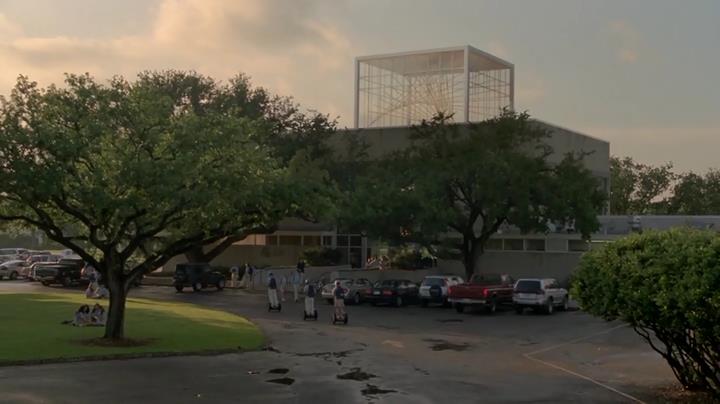

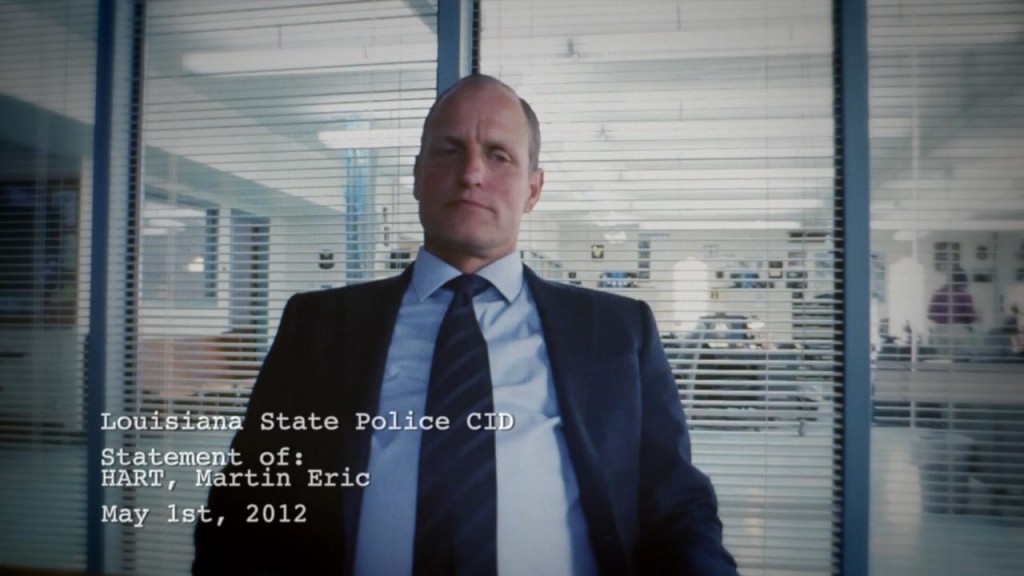

I don’t know if Pizzolatto or Fukunaga or anybody anywhere knows about this stuff besides my wife, and then me, and now you, but I find it fascinating and think about it all the time. There is so much going on in True Detective with straight lines and crossed lines and parallel lines; it’s everywhere. Here are two favorite examples, and then I’ll leave the rest for you:

I don’t know why that cross is reflected on his hood, but it sure as heck is. Maybe it’s because he’s out there working for Rust.

There are a lot of sly jokes in this picture, like the fake Hollywood puddles and the segway dorks, but look at that thing on the top of the building (and it’s definitely CGI). It’s a bird trap inside a box; it’s an endlessly over-refined lattice. You’re trying too hard, Reverend Tuttle, and you’re covering something up. I can’t believe they manage to get so much done with their straight-line language. Nic Pizzolatto must be a fair hand with a set of Lincoln Logs.

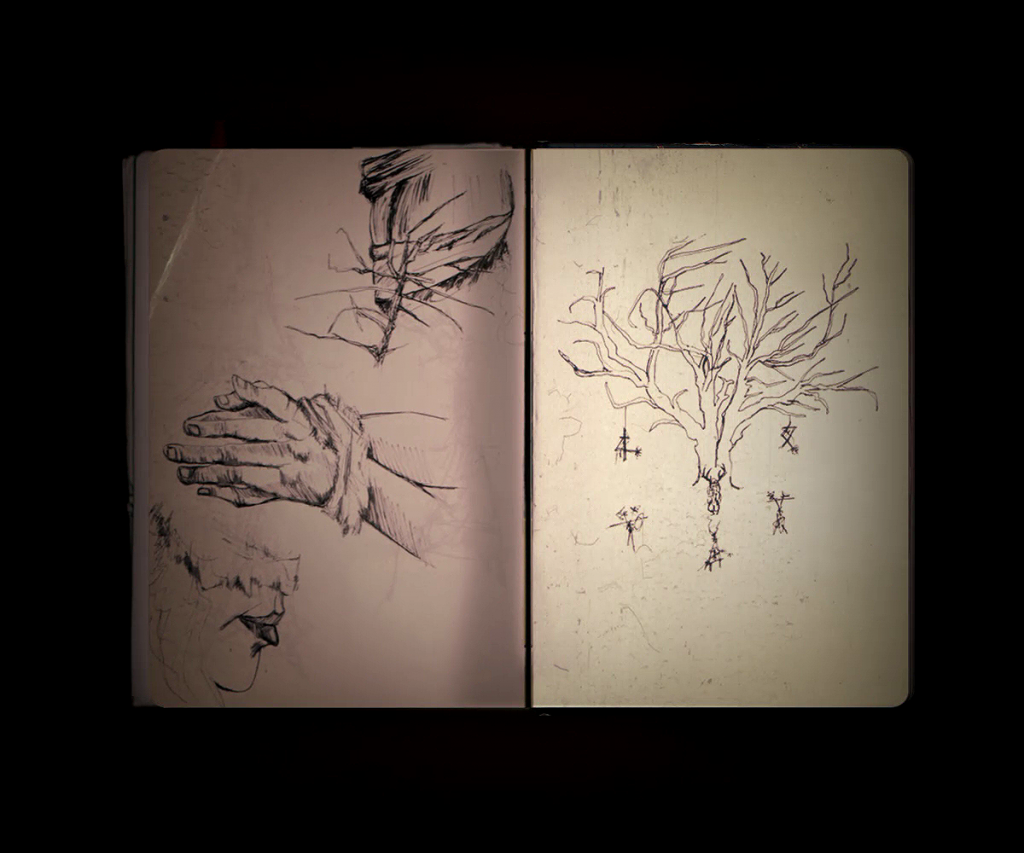

Crosshairs, parallel lines, bird traps, triangles, straight paths — I read somewhere that Chinese folklore states that devils travel only in straight lines, and there may be something to that — rays of light, abstraction, division — lines. Even Rust’s drawings are done in ligne claire style

Birds

Women are explicitly mapped to birds in this show. And I mean explicitly — every time a woman appears in the frame in the first couple episodes there is either a picture of a bird somewhere in frame or the sound of birds chirping. I’m leaning on the work of an anonymous internet commentator here:

There are birds in every shot there is a woman in EP01, either a live bird, or statutes like chickens and ducks (all over maggies room and kitchen) or an eagle (bar scene, police station), or the interview after dora lang with the woman who talked about “dove hunting” (swan and duck in that shot).

And every time there is a woman there are audible birds chirping. When they find Dora, (just when we see her there are birds chirping) and we hear birds chirping the first time we see maggie before she says anything (and there is a bird statue on the bookshelf behind her), and every time they interview a woman there is some kind of bird in the background, or birds chirping. Even charlie lang say “she can duck hunt with a rake” when he talks about Dora and chole says “a gaggle of hens”. Listen for the chirps in the scenes with women (except the bar). Even incidental characters like the secretary and the stenographer have eagle posters with them in their shots. The eagle shows up quite a few times. And when they go the church and talk to the black pastor he calls the stick figures “bird traps”, or devil nets. At the pitchers house there are chickens in the back yard.

I don’t know how they figured that out, but they’re right. Here are the images that commentator assembled, all from e01 and e02.

I’m satisfied with their scholarship: women and birds are often correlated in this show, especially in the first two episodes.

That makes the moment when the birds assemble into a spiral even more interesting, by the way.

Animals

Men and animals are different from women and animals in this show. Men are animals and it’s just the way things are. Women who are animals instead of birds, are having some troubles.

First the guys:

I know that fish are technically different from the land-based mammals we’ve been discussing so far but let’s just note that they are swimming away from him and move on.

Now the ladies:

Apparently if a woman is in the frame with a horse, she’s in trouble. Possibly because horses are animals that men ride around even when they don’t want to be ridden.

And then of course there’s Dora Lange, whose murder theoretically sparks this story. She has been brought to earth like a deer.

Dora is one of the rare women in this show to appear in solid colors, though her color is grey like dirt, and she is bearing the antlers of a ten-point buck deer (or “hart,” as deer were called in ancient times). She is no longer complex.

Erroll has penetrated the mystery of women and reduced it to this. He burnt the fields; no flowers there. But there’s more to it than that (and the tree is unharmed). Creeping, crawling vegetation means something in this show. The wild, growing nature of Louisiana, the hungry way that nature grasps them back, no matter how many refinery cities mankind builds nature patiently grows, and waits. The people in this show are ground between the lower jaw of refineries and the upper jaw of blind sweaty jungle.

And now a word about boats. Boats and symbolism. Are boats symbolic of anything in this story? Yes, I think maybe of two things, maybe of three. Here, take a look at this sequence:

I think what this sequence is trying to tell you is that, emerging from the tangled wild of Erroll’s monstrosity will come a boat carrying a bright red blaring siren of truth. And that’s what happens next. We cut to Erroll and his sister, the serial killer stands revealed at last, and then we pull away from his creepy gothic murder mansion exactly like this:

BOAT!

And on the boat the truth shall be revealed. Or at least one more little truth, that leads them closer to the big truth, which is…complicated.

This is like Tyrone’s name magically appearing on the wall. The lighthouse boat was there to alert us subconsciously, or to amuse us analytically, that the next boat we saw would be bearing the truth.

Does this mean that all boats bear the truth in this story? Well, there sure are a lot of crab fishermen and such who give clues in interview:

So, boats, man. Whatever boats mean. Boats are important. It’s all important, I guess, because what they’re trying to do is to enhance the investigation with salient story detail. It’s what makes a good story great — they lay all the sticks in the same direction. You know how much better a railroad works when the rails are all in a line and attached to each other and at the proper width and banked at the turns and supported with railroad ties and such and such? Well, a story is exactly the same way. When you build a story that works on as many levels as this, what you’re doing is building a mental railroad that efficiently downloads information into your audience’s mind with the least friction possible.

Plus it’s a lot of fun for the people who make the movie.

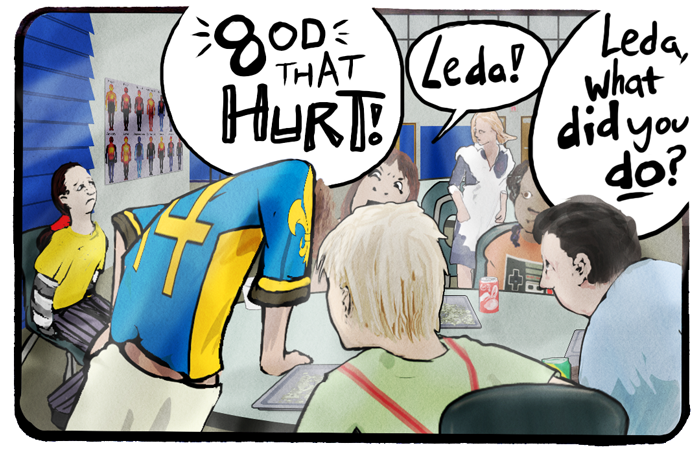

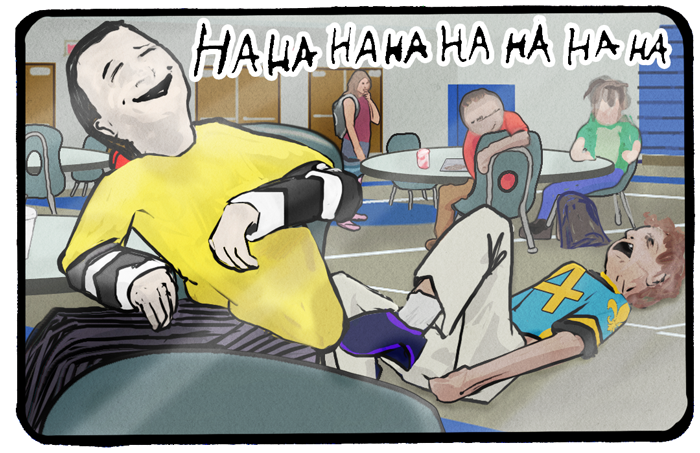

Think about it — and this is a problem for comic book artists too — you have a rectangle full of pictures, and your job is to stack as much information as humanly possible into every edge of that frame. How do you do it? What do you do? Should you grab some crap from around your kitchen, or try to recreate famous paintings, or try to tell little mini-stories with all the random stuff?

My advice: make a game of it. It’s a lot more fun for everybody if you make it a game.

Here’s one of my favorite moments for that:

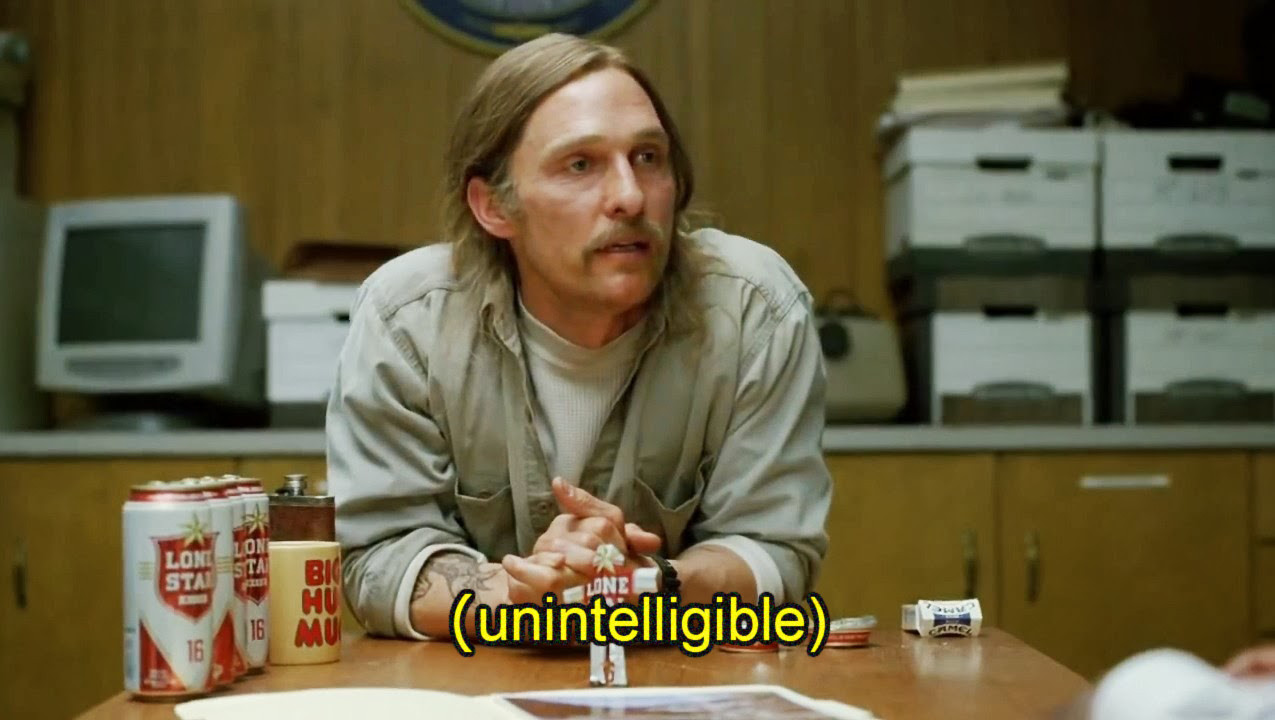

As you probably know, all the driving-around scenes are greenscreened; Woody and Matt are sitting in a fake car in a studio somewhere, just runnin’ their lines. That’s a great way to get great performances and all but let’s say that you’re on the CGI team and your job is to fill the screen behind them with plausible but visually interesting landscape.

As Cohle says, “It reads like fantasy,” they drive by a run-down trailer on stilts. Is this impossible? No. I’ve been to Louisiana, there’s stuff like that all over — this may well be an actual picture. What does it mean? Are they trying to say that people who live on houses on stilts are fooling themselves? Are they trying to say Dora Lange’s dreams are a run-down, shabby affair? Is it relevant that the trailer depicted is far from ADA-compliant and someone with impaired function (such as Dora) could never hope to reach the lofty heights of the living room?

Yes, yes to all those things. Sure, whichever, it matters, it doesn’t matter.

Who put it there? Was it somebody famous? Do we only accept creative input in this show from people whose names are famous? In that case, what does it mean that practically nobody ever heard of Pizzolatto and Fukunaga before this show? No, no, and no. It was put there by some random CGI dude and odds are decent that none of the names attached to the show ever noticed it. Doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter.

This is what happens when a creator uses their terrain. By utilizing basic and universal symbols, not only do they make it easy for everyone working with them to play along, to enjoy the game and make their contribution to the show and the characters and the story, but they introduce the possibility of “happy accident.” The Sopranos pioneered this. By treating the real world that we live in as filled with myth and meaning, by seeing our daily lives as worthy of myth, they transform the everyday into art. I bet whoever lives in that trailer thinks nothing of the meaning of their trailer. That’s for the artist to do. We provide a fresh perspective.

Artists are not always trying to create a platonic ideal. Quite often that they’re looking for a universal, and sometimes it’s enough to try to make you feel how another person would feel. To truly explore another point of view. I hope you’ve seen The Sopranos. If you haven’t, there’s an important miniplot with a Billy Bass.

Billy Bass is a robotic plastic fish that plays recordings of hilarious water-themed songs when you press a button and sometimes even when you don’t. It was all the rage of the mall at Christmas 2002 or something, and these wastes-of-plastic-and-sweatshop-sweat were all forgotten by New Years’s Day 2003.

But the Sopranos said hey, our main character is a mob boss who just had to murder his own best friend because he was working for the FBI, and he found out about it through a prophetic dream about a talking fish. And all this happened before Billy Bass came out, it was like two seasons previous to the great Billy Bass Craze of 2002 or so. What would a person like Tony Soprano think if they saw a Billy Bass?

This is not a problem most people have!

But it certainly is an insight into the mind of a Tony Soprano.

So what would happen, if you were Tony Soprano, is you would freak the fuck out whenever you saw one of those things. And the show conveyed that, admirably. It got us across to another point of view. For just one tiny moment, by grace of art, we got to visit a corner of what it’s like to be a mobster with a head full of bad dreams, and we got to see our zany media universe from an utterly unique point of view.

In the process, Billy Bass was enshrined and shall now live forever.

But that does not mean the genius who invented that singing fish had this in mind.

True Detective is similarly awake to the possibilities of our crowded world. It assembles things into classes, categories, patterns of iconography. As such it casts its influence far and wide, assembling truly disparate elements into a thoroughly satisfying myth. It doesn’t have to be in the script, and Rust doesn’t have to say “It reads like fantasy, like that trailer we just saw a second ago, did you see that trailer Marty?” True Detective generates sufficient mythic gravity that these little symbols fall into orbit.

This is part five of a six-part series about True Detective.

Here are the other five-and-a-half chapters:

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Six

Chapter Six-and-a-half

![TD s01 (1).mkv_snapshot_02.03_[2014.04.13_02.00.55]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-1.mkv_snapshot_02.03_2014.04.13_02.00.55-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (1).mkv_snapshot_00.18_[2014.02.15_05.50.58]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-1.mkv_snapshot_00.18_2014.02.15_05.50.58-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (7).mp4_snapshot_53.01_[2014.04.17_06.56.09]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-7.mp4_snapshot_53.01_2014.04.17_06.56.09.jpg)

![TD s01 (7).mp4_snapshot_53.12_[2014.04.17_06.56.21]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-7.mp4_snapshot_53.12_2014.04.17_06.56.211.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_06.31_[2014.04.14_04.29.14]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_06.31_2014.04.14_04.29.14-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_06.41_[2014.04.14_04.29.24]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_06.41_2014.04.14_04.29.24-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_06.45_[2014.04.14_04.29.34]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_06.45_2014.04.14_04.29.34-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_06.46_[2014.04.14_04.29.30]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_06.46_2014.04.14_04.29.30-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_06.53_[2014.04.14_04.29.42]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_06.53_2014.04.14_04.29.42-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_06.55_[2014.04.14_04.29.44]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_06.55_2014.04.14_04.29.44-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_06.57_[2014.04.14_04.29.45]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_06.57_2014.04.14_04.29.45-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (5).mp4_snapshot_47.32_[2014.04.19_04.55.40]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-5.mp4_snapshot_47.32_2014.04.19_04.55.40.jpg)

![TD s01 (6).mp4_snapshot_52.31_[2014.04.22_20.57.08]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-6.mp4_snapshot_52.31_2014.04.22_20.57.08.jpg)

![TD s01 (6).mp4_snapshot_36.47_[2014.02.26_02.17.27]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-6.mp4_snapshot_36.47_2014.02.26_02.17.27.jpg)

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_06.42_[2014.04.13_02.19.02]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_06.42_2014.04.13_02.19.02-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_16.24_[2014.04.13_02.49.17]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_16.24_2014.04.13_02.49.17-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_03.41_[2014.04.14_04.20.53]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_03.41_2014.04.14_04.20.53-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_03.42_[2014.04.14_04.20.55]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_03.42_2014.04.14_04.20.55-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_32.37_[2014.04.14_06.04.24]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_32.37_2014.04.14_06.04.24-1024x576.jpg)

![true.detective.s01e05.hdtv.x264-killers.mp4_snapshot_14.55_[2014.02.18_05.17.37]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/true.detective.s01e05.hdtv_.x264-killers.mp4_snapshot_14.55_2014.02.18_05.17.37.jpg)

![TD s01 (7).mp4_snapshot_53.12_[2014.04.17_06.56.21]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-7.mp4_snapshot_53.12_2014.04.17_06.56.21.jpg)

![TD s01 (2).mkv_snapshot_40.12_[2014.04.17_07.05.13]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-2.mkv_snapshot_40.12_2014.04.17_07.05.13-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (6).mp4_snapshot_26.59_[2014.04.17_07.10.24]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-6.mp4_snapshot_26.59_2014.04.17_07.10.24.jpg)

![true.detective.s01e05.hdtv.x264-killers.mp4_snapshot_22.01_[2014.02.18_05.27.13]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/true.detective.s01e05.hdtv_.x264-killers.mp4_snapshot_22.01_2014.02.18_05.27.13.jpg)

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_24.48_[2014.02.18_11.55.52]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_24.48_2014.02.18_11.55.52-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_29.26_[2014.04.13_03.06.03]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_29.26_2014.04.13_03.06.03-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (6).mp4_snapshot_24.37_[2014.02.26_01.49.09]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-6.mp4_snapshot_24.37_2014.02.26_01.49.09.jpg)

![TD s01 (4).mp4_snapshot_14.28_[2014.04.02_04.39.45]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-4.mp4_snapshot_14.28_2014.04.02_04.39.45.jpg)

![TD s01 (4).mp4_snapshot_14.35_[2014.04.02_04.39.52]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-4.mp4_snapshot_14.35_2014.04.02_04.39.52.jpg)