True Detective: One Measures A Circle Beginning Anywhere (the complete essay)

on May 6, 2014 at 1139This is a six-and-a-half part essay on True Detective, Season One. If you prefer you can read the chapters: Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Six-and-a-half

There’s too much talk about what True Detective does and not enough about how it does it. It’s like a great song with great music and all anybody talks about is the lyrics. That’s the way life is, I guess.

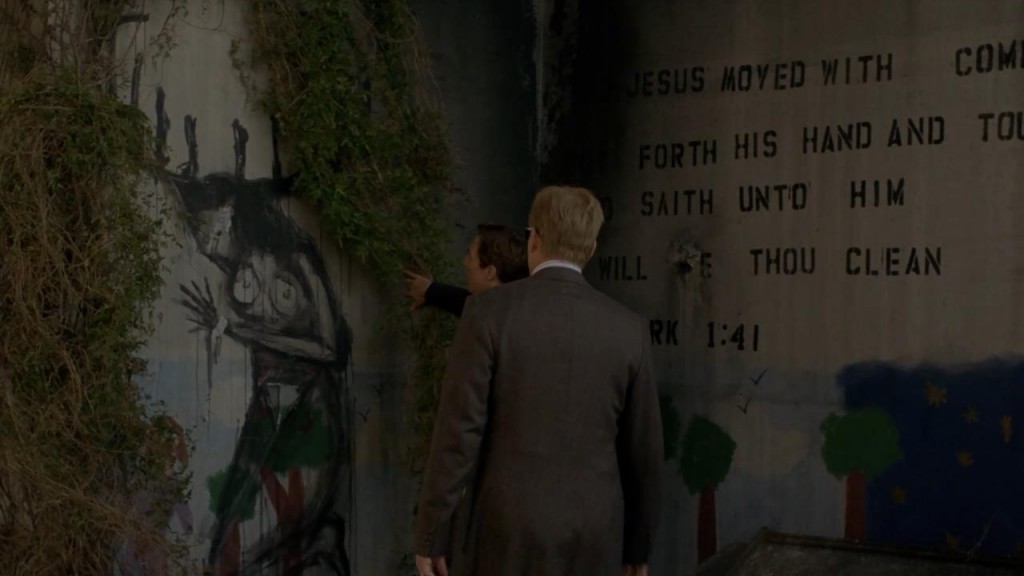

There’s this moment, in episode 4, when Charlie Lange, the incarcerated former paramour of Dora Lange, the woman whose death theoretically sparks this investigation, reveals to our fearless detectives the name of a character of no importance whatsoever. This character is called Tyrone Weems, who will be in only one scene in which he will do nothing but reveal one more clue on the trail of the dreadful Reggie LeDoux. Immediately after Lange tells them about Tyrone, his name appears written on the wall to the left of the detectives.

That’s the kind of show this is. The show reacts to the characters, the investigation appears everywhere. The coincidences are so manifold that you start to think that Marty’s family must be victims of the cult at the center of the case or something, because how else could they know enough to say things like this:

Maisey: “You won’t have a mommy or daddy anymore. They’ll just die in an accident”

Audrey (presumably): “How?”

Maisey: “In a car accident. Somewhere.”

if they didn’t know about the cult?

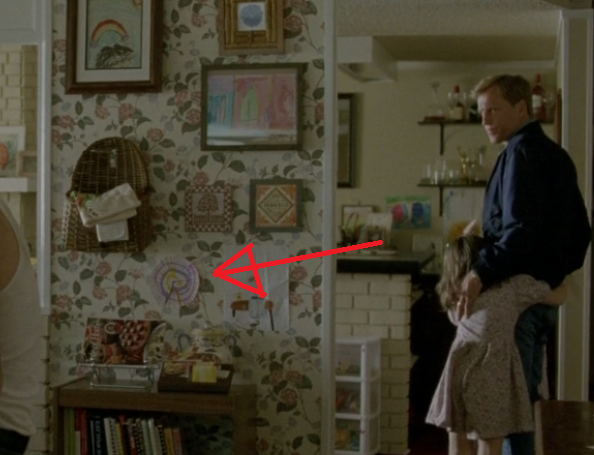

How could Marty’s daughter be drawing things like this:

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_24.48_[2014.02.18_11.55.52]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_24.48_2014.02.18_11.55.52-1024x576.jpg)

if she doesn’t know about the woman with flowers on her? Heck, she’s only in the opening credits. Has Audrey seen the opening credits?

How could a child’s drawing on Marty and Maggie’s bedroom wall in 1995:

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_29.26_[2014.04.13_03.06.03]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_29.26_2014.04.13_03.06.03-1024x576.jpg)

possibly appear here, painted large, on the wall of a mental health ward in 2002:

![TD s01 (6).mp4_snapshot_24.37_[2014.02.26_01.49.09]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-6.mp4_snapshot_24.37_2014.02.26_01.49.09.jpg)

….and with that the conspiracy runs aground.

Okay, there is just no way. Shadowy government conspiracies abusing the daughters of cops, sure. Sinister cults that take kids’ drawings and turn them into giant institutional wallpaper patterns so that their parent’s coworker partner can seven years later (not) find them…no, I can’t buy that conspiracy. That’s Illuminati-level nonsense. This thing may go deeper than anybody knows, but it doesn’t go that deep.

But that doesn’t mean that the choice wasn’t made on purpose. It means that it was a purely symbolic choice. For whatever reason, this story wants us to think about those flowers and these flowers at the same time. The universe reacts to the investigation, the story reacts to the story. Time is a flat circle and everything happens, over and over again, on every level.

It’s an impressive performance. I’ve rarely seen a work that speaks this clearly on the symbolic level. That’s why I’m so excited about this show.

Let’s get this out of the way, because this applies to every element that we discuss. Did the writer “put” it there? Did the director “put” it there? Did the production crew “put” it there? We’ll never know. But it’s there now, and we’re discussing the film as it is, so let’s talk about it. We’re not trying to recreate a holy text, we’re figuring out how to use this stuff for ourselves.

I don’t care if every single time Marty stands next to a triangle-shaped arrangement of sticks is a wild coincidence, now that I’ve perceived it I can use this in my own work. True Detective demonstrates how symbolism can be deployed consistently and accurately when you tell a story. Now that we know how, we can all do it.

True Detective found a new way to look at sunsets, and then applied that knowledge to a movie about two buddy cops who hunt a serial killer. It’s that simultaneously revolutionary and commonplace.

So now we know this thing is working on this level, we know to pay attention. For example, we know to pay attention to the color yellow:

You see that yellow blotch on the frame there? It’s not a speck of popcorn on the lens. It was actually added with CGI. Seriously. The creators of the film are expressing the symbolic language of this moment through a bright yellow mistake.

Much is made of yellow in this story. Much is made of many small things. True Detective is a very focused piece of craft. They want to evoke specific myths and fictional constructs through the lens of a perfectly genre show. So True Detective is exactly what it promises. It is the perfect noir cop buddy pic for the ages, and if that doesn’t sound good to you then you will not like it.

So, in the part of the article that you have read so far, I have blundered into at least three major areas of True Detective study and probably a few more that I’ve yet to notice. The three things that I keep returning to in this show, over and over, are:

1. Use of color and background to tell a coherent symbolic story.

2. Background detail that reacts directly to the story’s internal logic instead of external logic. The clearest example of this is, of course, when Rust sees the birds:

3. Awareness of narrative and the specific functions of specific narratives, from old cast-off weird fiction ideas like the King In Yellow or the Narrator Who Slowly Goes Mad to other delightful bits of folklore like the Prisoner Who Kills Himself After A Mysterious Phone Call and the Methhead Who Microwaves His Baby and the Hot Girl Who Was All Over Me And I Just Couldn’t Help Myself, because this all leads to the bigger picture; the lies men tell to justify adultery, the rationalizations policemen use for brutality, the way we tell stories to keep ourselves going on. And it culminates in Carcosa, in contact with an utterly alien consensual hallucination — that’s an interesting place for the story to go!

Until I realized that #1 is leading directly into #2, parts of this story were very confusing to me.

For example, the massive story-breaking coincidence of Marty meeting the girl he gave money to at the bunny ranch all those years ago at the exact moment that he decided to fall off the wagon and get a drink at a bar that just happened to be next door. It only makes sense one of two ways; if there is a story-spanning conspiracy by powerful figures to undermine him, or if the background reacts to the foreground. The latter is obviously true, unless you’re willing to come up with a story that answers why the governor of Louisiana wanted a child’s drawing of flowers to be found in both Marty’s bedroom and in the hospital ward.

Maybe this scene happens in an alternate universe where beautiful young women hit on bald men who can’t figure out their cell phones.

The truth is, and this truth would be obscured in a less carefully-created piece of fiction, the story reacts to the characters. Any particular creator may or may not have intended this at any particula moment, but this is the document that we have before us. True Detective is the record of the psychological reality of some imaginary people. It is not “perfectly realistic” and it does not wish to be. Rather, what we are seeing is the main character’s side of events. We’re seeing the story that the characters tell, not the events that led to the story. It’s a crucial difference.

Whether we are seeing the story that Marty tells himself to explain why he had an affair, or if we are simply failing to correct for the dramatic pressure that causes things in movies to happen too quickly and to people who are too pretty, it amounts to the same thing. Marty’s fall at the Fox and Hound is not a literal fall, it is a literary fall. This story revels in the fantasy that it all matters.

In this show they are selling one thing; that it all makes sense. That there is an underlying rhythm to reality, and by living in the right way and taking the right drugs and being a general desperate bastard you can perceive it. You can never control it and you can never, never understand it, but it is there and it can be seen. Sometimes. Sometimes, when you’re watching True Detective on TV, it seems like it all makes sense.

And of course that’s how it’s supposed to feel.

This shot is in the opening credits; this is one of the iconic views of the series. It is a picture of our fearless heroes as they urinate:

Yep, they’re pissing. Watch the part if you don’t believe me — seventeen minutes into episode three — there are even sound effects.

So that’s the kind of show this is, where the iconic shot is of the characters pissing. The annoyingly, obnoxiously, provocatively honest type of show. And it’s a show about men.

Think about it — the first time you meet Marty, he tells you exactly who he is.

Leaving aside how clear his anal fixation is made in the show (and I hope we do get around to that particular issue), leaving aside the show’s repeated castration anxiety, leaving aside whether or not this is a fit subject for a piece of TV, 1995 Marty’s a dick. Literally. He has no conscience to speak of at this time, he’s out for fun and fuckin’.

2002 Marty’s a dick too, but he’s gone soft. That’s why they call him “the human tampon.” Why, he is even buying tampons in bulk:

But by the end of 2012 Marty gets his mojo back, because guns, baby…..ah, the unwritten rules of American television writing. It’s interesting that Marty does the lion’s share of gunplay in the series. He shoots LeDoux once and Childress three times, and we see it happen every time. When he shoots LeDoux oh boy do we get a good look. I would like to think that is an accurate depiction of severe head trauma, so that I know what I hope to never see in real life.

Rust’s more complicated. He pulls his gun twice (on DeWall and Childress), doesn’t take the shot on either occasion (both people he’s aiming at run away, which I would think would be difficult because bullets run faster than people), and he only gets around to shooting Childress after extreme headbutting has failed him. Marty shoots Childress too, but with that guy the head shot’s the only true stopper.

That’s pretty much it for gun battles in the series, except for the sheer mayhem of the drug raid in episode four where everybody’s shooting everybody, except for Rust, who chooses to punch his way out of problems. Rust also uses the AK-47 at LeDoux’s hideout, but that’s only to cover up the fact that he’s crying.

That’s the only time I can think of that Rust is shown firing a gun on the show.

So Marty’s a dick. And Rust is all head. This is a superficial observation that has been multiplied through every layer of this story, as only life and art can do. In every way we are shown that Marty Hart is like a penis and Rust is like a brain. What does it mean? Well, if I could tell you then Pizzolatto and Fukunaga and all the other people involved would not have to go through so much effort to create this myth in order to tell you about it. It’s too deep for a single sentence in a blog post.

Most people think of a story as a gem or a stick of wood or something that is. It sits there on the ground and you can appreciate it or you can not.

This is not so.

A story is a machine that creates myth, and the motive power is your attention. When you watch a show, when you read a story, the imaginary gears do grind, and the fiction takes your attention and patterns it and influences it and creates something that is, hopefully, meaningful to you. The myths — the shadows thrown by these archetypes and universal situations — are supposed to get into your mental operating system and help you in some way. You try pick the machines that produce the exact mental effect that you want, but it’s far from a science. More of an art.

By taking a superficial observation like “Marty’s a cop and like many cops he’s a dick and like many dicks he’s obsessed with vaginas and anuses and fears of castration” and multiplying it on every level of the story, a resonant effect may build. You don’t have to know exactly what it means to create it; in fact, you create it because you want to know what it means. Marty’s a dick. He’s a dick in every way, every time. He does, inside the story, what a dick would metaphorically do if it was a walking talking person. This is a power of myth.

What does this mean? Let’s make it and find out. Let’s build the machine and run some human thoughts through it and see what we get. And I’m not exaggerating here; this is exactly what happens. Artists, filmmakers, and writers are technicians. They are technicians who create thought. Repetition of ideas in different modes is one of the basic techniques. They don’t know what result the machine is going to spit out before they build it — if they did, why would they bother building it?

True Detective is, to a large degree, a critique of men. It’s a critique of its audience. It’s a critique of the sort of men who would watch a show called True Detective.

Many of the accusations of sexism against this show spring from this, because it’s a powerfully male show. It’s a show about men, and how men perceive women, and how men fail to understand women, This is a show that was custom-designed for two kinds of folk: stupid men and smart people.

Genre

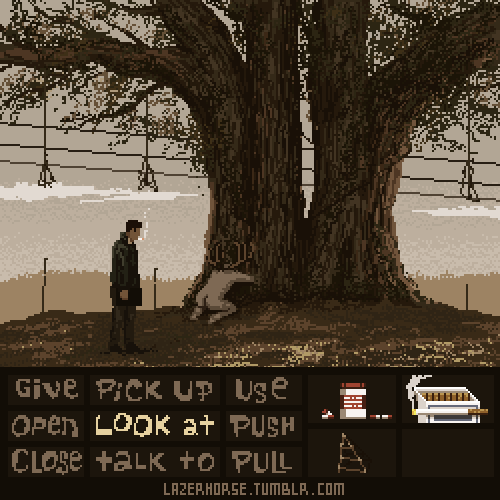

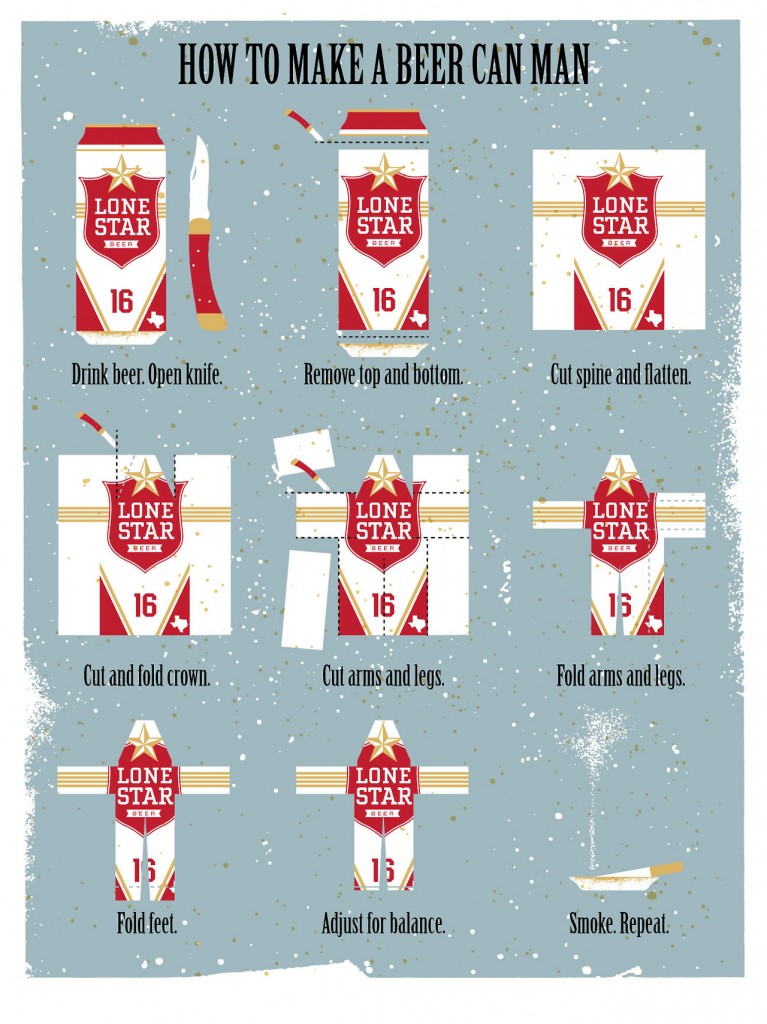

of all the various pieces of True Detective fan art, this is the one that I most wish I had made. Whichever internet adept made this, I salute you.

True Detective does something that I think I admire. It is an honest show. It is truly a show that you would expect to see if you were to see the words “True Detective.” It takes its name from an old pulp magazine and it fulfills the promise of the pulps. When you watch this show you are watching two shows at once, and one of those shows is totally and completely 100% in its genre.

I think this might be great. I’m not positive. It isn’t the only way to do things. There are movies out there that critique their audiences with a wink and a nod, movies like Starship Troopers and The Shining. Those movies have multifold joys for intellectual audiences, who can’t really enjoy an action movie without somebody there telling them it’s okay to enjoy the blood and callous disregard for consequences. Smart people love Starship Troopers because it’s an idiotic film made in a really smart way and it’s nudging them in the ribs the whole time; “See how dumb this is? Can you believe people really believe this stuff?” And that’s cool, and I like it. I like The Shining, I get to watch my movie about the haunted hotel and think deep thoughts about how historical responsibility is like a haunted hotel.

But let’s face it, we all know why Stephen King didn’t like Kubrick’s version of The Shining. It’s because Stephen King himself was in the book, as both the boy and the man, and in the movie both the boy and the man have been transformed into submoronic cavemen who can’t write books too good.

These wink/nod movies, they have the unfortunate effect of pissing their regular audience off. Your average fratboy can’t tell why Mazzy Star’s “Fade Into You” is playing during the awesome fistfight scene, but he knows that they’re making fun of him.

Taxi Driver and King of Comedy perfectly straddle this divide. Watch Taxi Driver…if you’re a tough fella, this is your kind of movie! It’s about a shrimp who has some problems but he eventually shoots the right bad guy and everything is great. But hey, it sorta seemed like the ending….maybe……might not be real. Like the ending might be a little too good. Then you watch King of Comedy and you realize, yeah. That’s a dream. And Taxi Driver was a dream too.

True Detective is in the second camp. It is its genre. It is a buddy cop movie about two men who unite to take down a deranged serial killer or two, exactly like Se7en, except this one goes to 11. They’re fighting….multiple killers! Serial killers! In a cult! A powerful highly-placed government cult! That rapes! And kills! Women! Poor women! Girls! Little girls! And videotapes it! And it’s been going on for decades! And they do weird things with the corpses! Oh and also incest! And did I mention drug dealers!

Our culture simply does not have any more exclamation points to give. We honestly cannot imagine anything worse than what happens in True Detective, short of genocide. The government pedophile rape cult is the single biggest American bugaboo there is; it pushes all our buttons, in order. This show is missing….cannibalism. Cannibalism and drunk driving. And dying alone in a nursing facility, and home invasion. I really can’t think of any other American fears. Snakes.

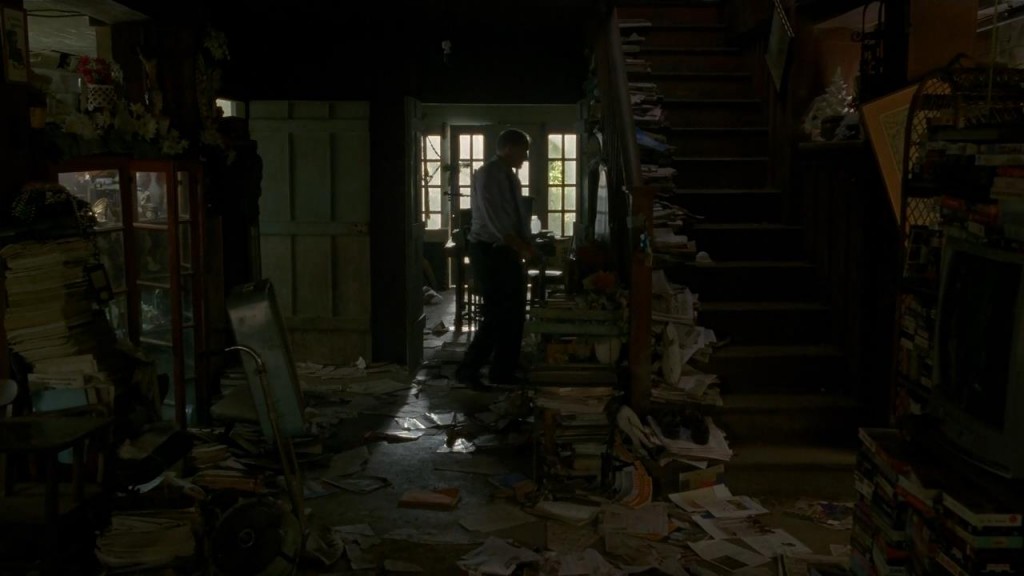

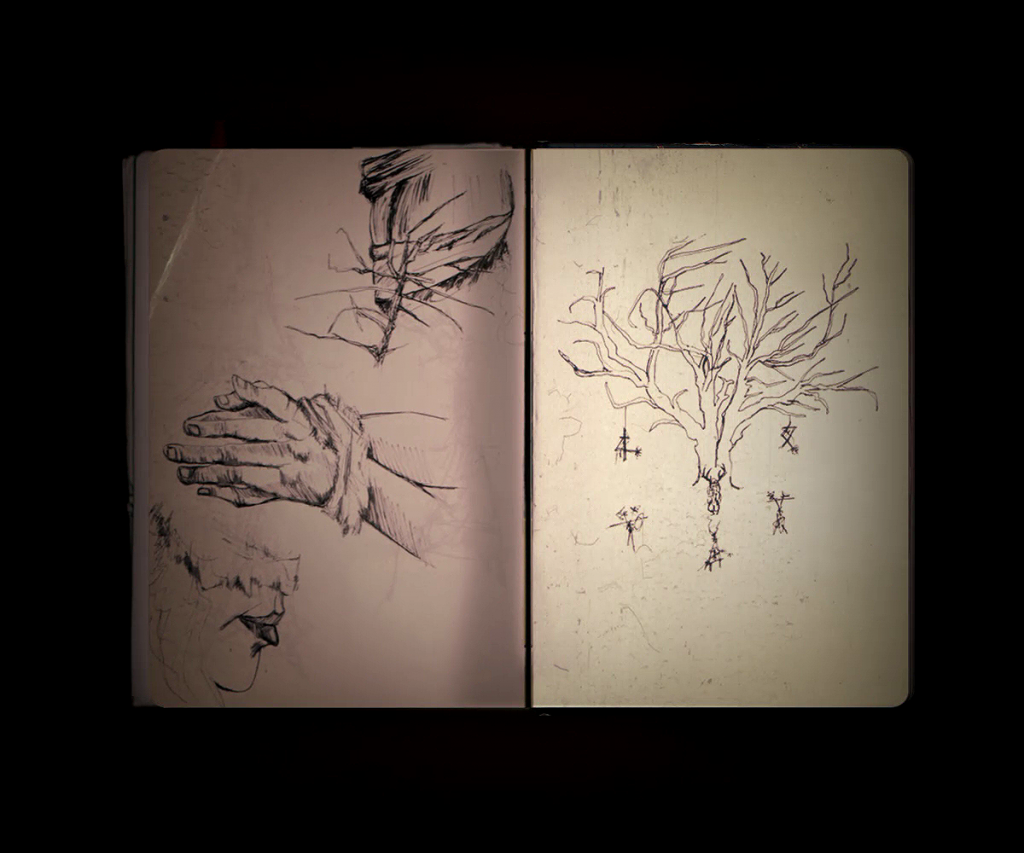

There’s season two for all that. The important thing here is that they gave us the worst crime our culture can reasonably imagine. Here is the Se7en to end all Se7ens. The serial killer lair has been radically expanded; he even has his own Civil War fort now! But he still kept all his crazy cool serial killer diaries:

They are not setting the controls for the heart of the sun by accident. This is “everything and the kitchen sink” storytelling and I like it. This show says “We have eight hours to finish this genre off; let’s do this.”

This is the show that Martin Hart lives in. Marty’s a regular joe who thinks with his regular dick, and besides being good at his job he is bad at everything else in his life. He is a hen-pecked husband with kids that are getting away from him and he’s going to soldier through (why doesn’t his family support him and appreciate him like they should?) and he’s going to get to the bottom of the Worst Crime Ever. Which he does, by doing Good Detective Work and Tracking The Villain To His Lair. And then, as a reward, he is Reunited With His Best Friend. Marty does not see anything supernatural because he is not in that movie. There is no giant CGI at the end because Marty was not in that movie, and this is Marty’s movie. This movie is for all the Martys who watch it, for all the men in the audience who don’t understand that their wives actually do understand them, they understand them all too well. He is meant to be them, he is all their little mistakes and their little errors and their bright, glistening rationalization, that They Are Good Guys Deep Down and At Least They’re Good At Their Jobs. I’ve thought several times, watching this show, that this is a bartender’s-eye view of Men. This show collects all the half-assed excuses, bullshit promises, and self-serving masturbatory blindness that one bartender has ever heard and loads them all into the character of Marty Hart.

This is Marty’s big case, and this is Marty’s show, and there has been a principled decision by the authors of True Detective to let him have it. Nothing ever violates the buddy movie that he’s in; you could watch the movie like that and you’d be just fine. I’m not sure, but I bet this program is plenty popular in frat houses, military bases, firehouses, and all the other traditional male enclaves you can think of. Not because those people are dumb, but there sure are dumb people among them, and True Detective offers something specifically for them and has the decency not to ridicule them for wanting it.

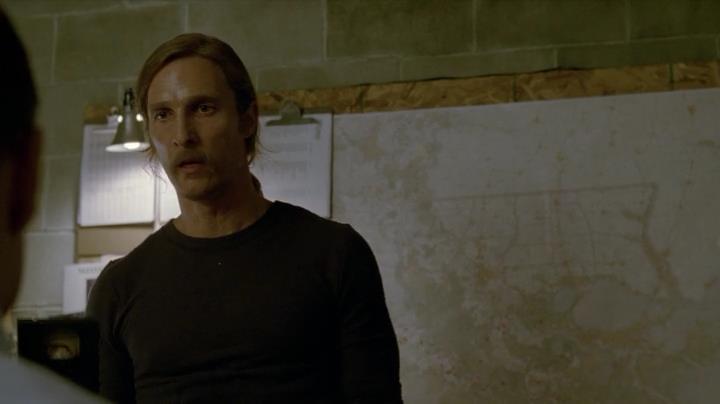

Now, as to the other detective, Rust Cohle. “Cold” of Detectives Hot and Cold. Rust never sleeps. Rust is the brilliant bastard bartender, aiding and abetting, guiding the drink to his lips and understanding that Marty doesn’t really understand, but he also trusts him. He gives him what he needs.

Cohle is the thought track. He’s the commentator. He’s not the heart of the story….that would be Detective Hart. He’s the mind, though.

And Marty’s prize, for surviving the story, is to get to help to bring his friend back to life.

The important thing is that Rust does not get in the way. He does not make fun of Marty, he does not do anything but make the story happen. He lets Marty and the audience have fun, and there’s nary a snigger or a smirk. That’s a fine line. I like that way of doing things a lot. It seems profound to me.

True Detective is truly True Detective. That’s what I’m trying to tell you. You can have your badass action movie and your complex philosophical exegesis at the same time. Think of all the time you save! You’re improving your soul AND being entertained at the same time — it’s like reading in the bathtub!

See what I’m saying about a story that’s designed to do something?

So this is what I’m talking about when I say this show is aware of stories, of how stories work and what stories do, and it combines stories in a very specific way to create very specific, and as it happens emotionally resonant, effects.

So you’ve got the story, which is a detective story. And you’ve got the stories that are inside the story; the King in Yellow, the terrible way that drug cartels kill their victims, the serial killer who arranges his victims in bizarre rituals, all these things are deployed and arrayed. Let’s talk about the way the background comments on the story.

A Visual Bestiary

Part of the joy of True Detective is that the writer, director, production staff, and for all I know the caterers conspired together to tell a thematically coherent movie. This was not done in the usual way, by relying on an oracular David Lynch-type to make everything fit just so, but by careful collaboration between a writer who wrote a script, a director who understood it, and a crew that made it happen. It isn’t as much fun to play these games with other shows, because they aren’t aware, they don’t hang together, they contradict themselves. True Detective takes the time to make everything clear, or close enough to everything that you can get the rest of the way there by yourself. Everything in the universe of this story bends itself to the investigation they are in, this discovery that they are on.

In this sense, from this perspective, the actors are guys who stand on a piece of tape and say some words. They create the story, they invite the story into existence, but we’re not exactly talking about them so far. All the driving-around scenes in this movie were shot in a studio in front of a green screen (that’s why you rarely see a shadow travel across their face in the car) and the perfectly moodly background was colored in with computers.

Would it surprise you to hear that the reflection of the telephone pole appears at the right moments to emphasize his words?

One of the main ways that this show tells you what’s going on is color, and I don’t mean in any hippie whoo whooo sense. I mean isolated patches of solid color, and they are everywhere in this show.

You mean to tell me it’s just a coincidence that those blue and yellow shirts are on that particular clothesline?

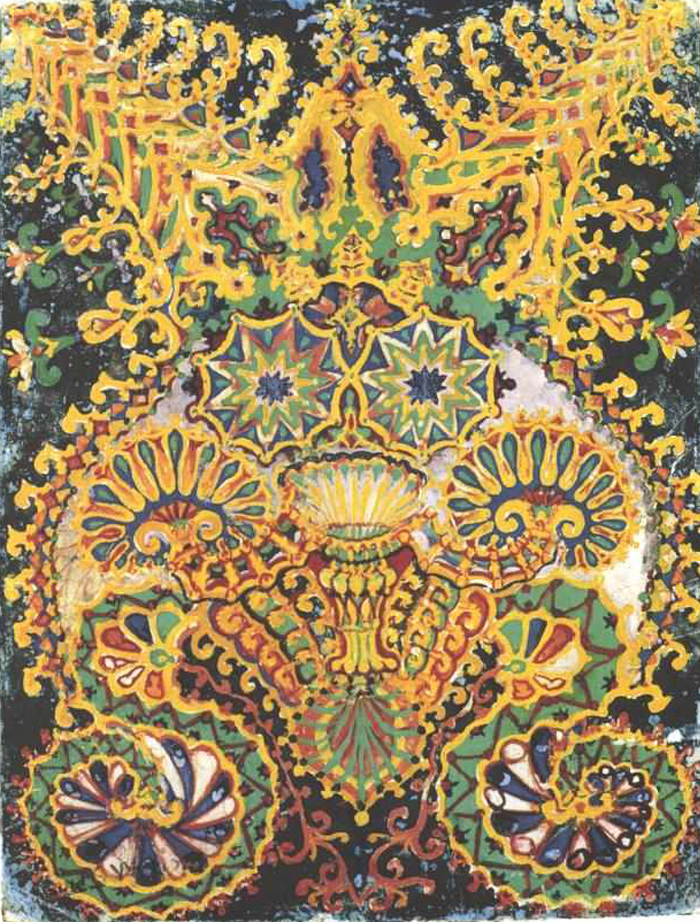

Another: pattern. Complicated, difficult people that Our Fearless Detectives cannot easily understand get patterned clothes and patterned backgrounds.

That map behind him is always on the wall but it only seems to get in the shot at certain specific times. More to come on this point.

Women are pretty much always wearing patterns in this show, which says a lot about the way that Rust and Marty relate to women.

There’s a lot going on with floral patterns, and flowers in general, and plants in general. Here are some examples of the use of thick vegetation.

Another is animals.

Another is birds.

The tattoo on Rust’s arm. Maybe, just maybe, in difficult symbolic language, it represents how he feels about his dead daughter or something.

Seeing as it’s a bird and it’s dead.

Don’t say these things are too simple to be symbols, or “Well of course in Louisiana you’d find kudzu.” Of course. The creators knew that too, and chose to use it. They use their terrain, they use it well.

Look at that list:

solid colors

patterns

plants

animals

birds

Those are not complicated things! Anybody can do this stuff. It’s using the things around you to tell a story, and it’s a great way for the production staff to keep themselves interested as they try to figure out how to stuff a frame with information for eight hours straight better than anybody else ever. It’s a game. If you want to express that something is feminine and otherworldly, put a bird on it.

Of course it’s not fair to use the exact same symbol set as True Detective, but most of the stuff is pretty simple. Patches of solid blue equals “the job” or police work, you see that over and over. This show didn’t invent the association of blue and police. But you have to give them credit for assembling it into their bestiary of symbols.

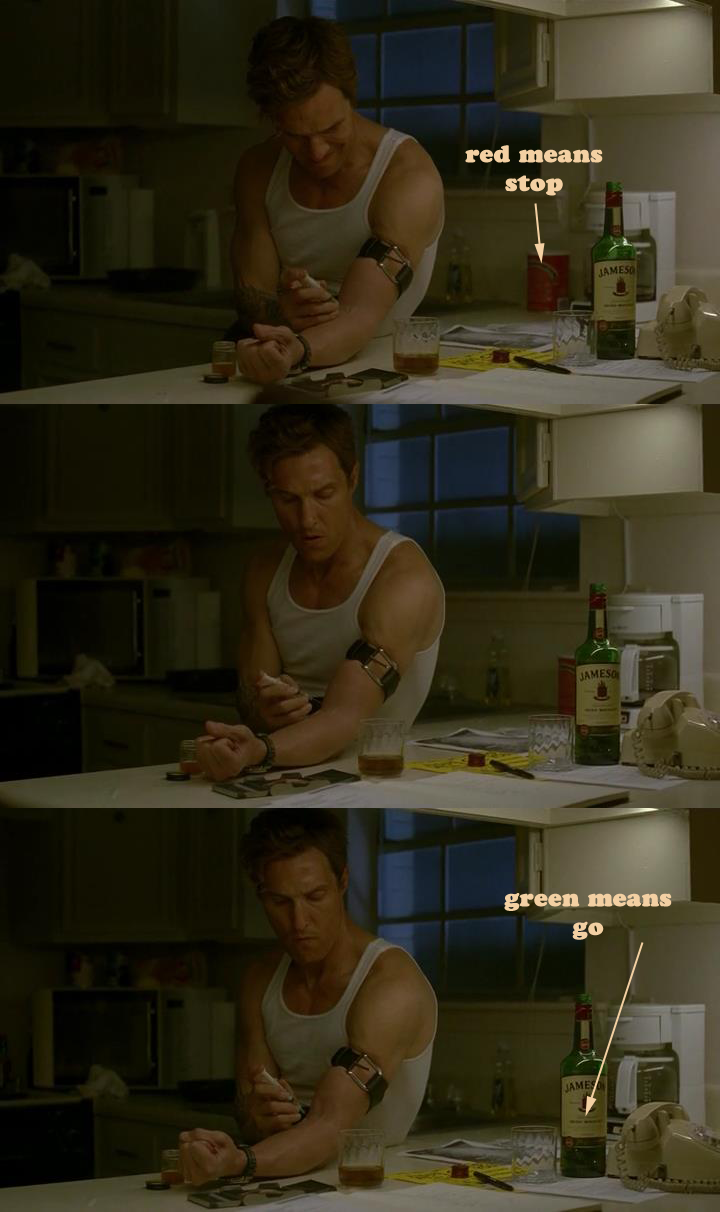

This is one of my favorite shots in the series:

You might think this is weird, but this is the shot that made me write this essay. When I saw this I just started laughing. This is from the scene where Marty goes roller skating with his daughters; in just a second he’s going to emerge from that mist to have an uncomfortable and awkward conversation with Maggie.

This is a scene about Maggie’s reconciliation with fate, and a fate that includes Marty, not about her reconciliation with him. Red and green parallel paths — mixed signals — symbolically that’s about as clear as it gets. I’d been watching the growth of the symbolic language of the show with rising glee (and at the time I was more or less unaware of nearly all of it), and that shot was an unmistakable signal that yes, they were speaking this language.

I find it so refreshing, so utterly delightful that someone has a) figured out how to tell stories like this b) figured out how to get those stories made and c) figured out how to get paid. Tell your laser stories, sir! I’m all ears.

The ending suffers from one simple drawback: it’s not the best episode. The fourth episode is the best episode. The fourth episode is a peak TV experience and if every episode of this show was as good as the fourth episode then everybody could retire and we could all go home and just watch True Detective season one over and over again. There would be no need for season two. But they have yet to perfect the art of television, and episode eight is not as mysteriously magnificent as episode four. Oh well, sorry.

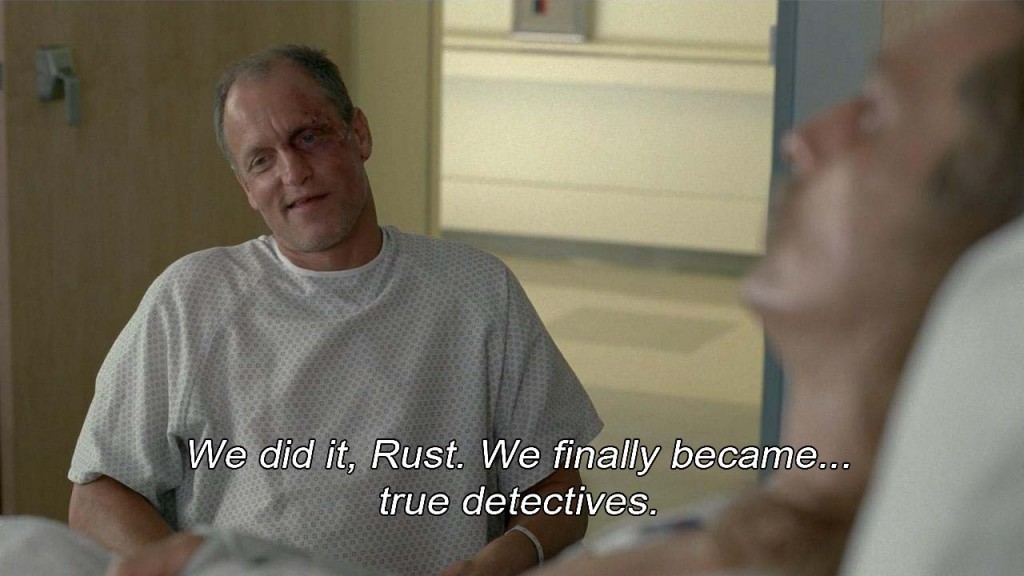

But the last episode does have plenty to offer, so pay attention. It doesn’t end with a grand resolution and it tells you that it’s not gonna near a million times before it gets there.

The story closes with some tantalizing clues to the mystery behind the mystery, a fascinating dissertation on consensual hallucination and the meaning behind Carcosa, the resolution to the buddy detective show that we’ve been watching this whole time, and then a sparse and human moment in which a lonely man makes peace with the spirit of his dead child. It’s not really the ending; it’s just the last episode.

No less a luminary than Scott Snyder, some guy who writes Batman, wonders why Marty did not experience the supernatural element (singular) of the last episode. He wonders why poor Marty didn’t get even one CGI for his own.

True Detective is a show that plays by the rules. It’s genre entertainment, and it delivers that genre precisely. Now, it’s genre with something extra, and that’s why we love it. But the buddy-cop-versus-serial-killer story thumps through it all regardless, and it is delivered upon with no subversion or subterfuge.

It’s obviously a purposeful choice, and I believe a principled one. Unlike wink-and-nod satires like Starship Troopers and Full Metal Jacket that allow people to have their fun action movie and feel superior to their fun action movie at the same time, True Detective plays it perfectly straight. It doesn’t subvert the genre at the end to prove that it’s smarter than the genre. Nothing “supernatural” happens to Marty because Marty simply isn’t in that type of movie. Marty’s the straight cop in a buddy cop movie that’s bigger than he can understand. If Marty participates in CGI shenanigans at the end of things then you’re not watching a film noir with a metaphysical commentary track, you’re watching an exquisite episode of the X-Files.

Marty is sheltered.

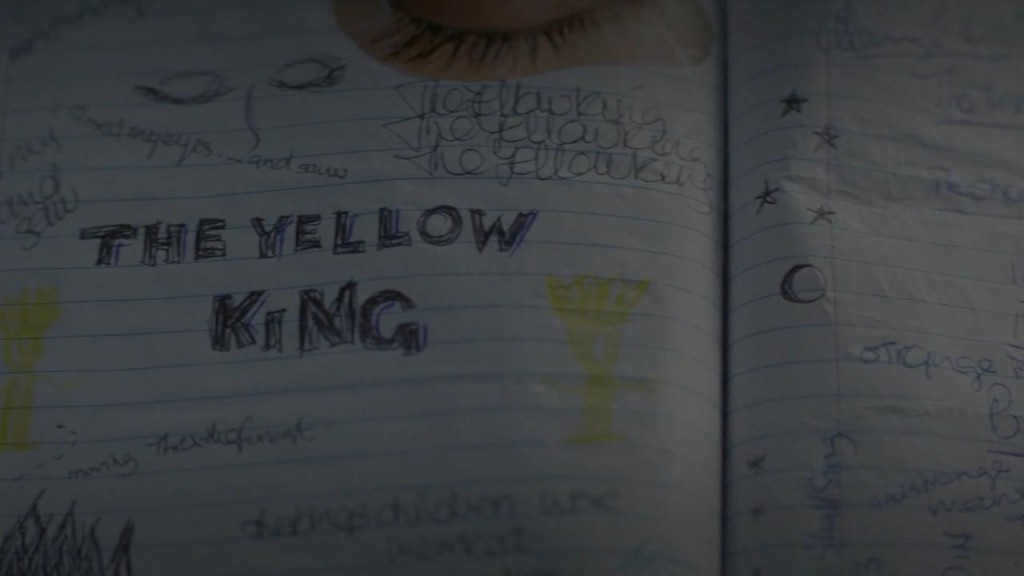

Part of the game here is that everything is real. The King In Yellow appears not just as a name, but as a concept.

The King In Yellow

In 1895 Robert Chambers wrote a book about a play, and in that book people who went to see this play went mad. Lovecraft picked up this thread in the 1920s made references to the King in Yellow in his books, adding the character to his pantheon (from which the King in Yellow eventually came to be known as a Dungeons & Dragons monster, but our examination stops short of there).

The writer of True Detective, and this is the point that has opened my mind to a new dimension of storytelling and won my eternal respect, picked up the concept of the King In Yellow and put it into his story as clearly and cleanly as you would put a new carburetor in your car. He even uses the concept three different ways, to make sure you get that he’s doing it on purpose. It’s stylish, I’ll give him that. It’s one of the more impressive feats of literary wizardry I’ve ever….I don’t want to say “seen.” I’m sure there’s stuff this clever going on in a lot of great stuff. But it might be one of the greatest feats I’ve ever been aware of.

So the story uses the symbol of the character of the King in Yellow, as if they were a real person, a King, wearing yellow clothes.

They use the King in Yellow in the cosmic, Lovecraftian sense, as Hastur, the monster beyond space and time.

And they use the King in Yellow in the Chambersian sense, as a symbol of madness and a play that drives men mad. And that raises the interesting question.

We know what a guy in yellow looks like.

We know what scary monsters from beyond space and time look like.

But what kind of play could drive men mad?

What kind of thing could you watch that would permanently damage your sanity?

True Detective answers that question: a videotape of some extremely terrible things happening to a young child. Everyone who watches it feels furious and sick inside. It is a cursed object:

So the Play That Drives Men Mad is brought to life as A Real Thing in this show. By plugging those two concepts together, even if everything else about the show was discounted, Pizzolatto would have earned the undying respect of weird fiction aficionados. We’ve been asking ourselves for decades, “What kind of Play Could Drive Men Mad?” and he answered our question. The answer had been pretty obvious all along, but at last somebody got around to saying it, and once we heard it out loud we knew it was the truth.

There is nothing Lovecraftian about this at all, except for all the things we associate with Lovecraft but don’t think of as Lovecraft. This show doesn’t use his invisible sky fiends — it assimilates and appropriates his story style. That’s a wonderful trick. Like I said, I find this inspirational.

What is Rust Cohle but the Lovecraftian narrator come to life? He sits down with his pad of paper, or in this case with his interview room with two witnesses and a camera, and he slowly goes mad. He starts making little dolls out of beer cans.

I’m not sure what that means besides the symbolic, by the way. There’s a repeated motif of five men standing around one woman:

Basically the only reason to not decipher this as some sort of gang rape analogy is that it maps perfectly to Marty, Rust, and the troopers at the crime scene.

The five beer can men around the one flat can. Rust gets it. Curiously, the five/one beer can sculpture is shown in blurry form along the bottom of the screen several times, but it’s only shown completely in this, the very last shot in the interview room.

I don’t know what it means but it does not spell good news for the woman. There are those who say Rust was doing that as a coded message to the interviewer’s bosses, so they would know he was on to them. Yyyyyyyyyeah maybe. That does make some sense. The show almost casually provides men in high places to be behind these terrible crimes, and the rigid dramatic rules of the show, where every move stands for something else, imply strongly that Senator Tuttle would be brought down by these revelations.

But Rust goes reliably mad, as he tells the tale of the Dora Lange investigation, he descends into cosmic horror and vague ranting, much like this article itself. It always happens that as you go deeper and deeper into the truth behind the truth the farther it takes you from other human shores. That’s why we try to build these bridges.

It’s not supposed to be easy.

Carcosa

I’m positive there’s a lot about Ambrose Bierce in this. Bierce was a veteran of the Civil War who spent a lifetime exorcising his bad dreams by pouring them into American literature. He’s mostly known for An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, the story that created the “the main character was dead the whole time!” plot point that you’ve seen so many times in [SPOILERS] and [OTHER SPOILERS], but Bierce is a pretty significant writer who wrote a lot of stuff way back a long time ago. He’s one of the founders of what would become weird fiction, then pulp fiction (where True Detective determinedly plants its roots), then horror novels and horror movies and modern horror. They’re going way back in the family tree for this show, to the root of American horror, in the American War.

It’s very interesting that the taproot goes exactly back that far and no further. There are several times in True Detective that it is implied that the “conspiracy” or the “problem” goes back to the Civil War, especially when Carcosa is revealed to be an abandoned Civil War fort. Curiously, the fort is not in the script, but it is in the final product, so it totally counts. Though Pizzolatto is the originator of this story, he’s far from the only progenitor. The color and background stuff that I’m about to get into is obviously not the product of the author, but it is essential to the story. To put it another way, he may write the song but it’s the band that plays it.

Bierce created Carcosa in this very short short story: An Inhabitant of Carcosa. It’s basically a tone poem about not much besides death, ruin, and decay. There’s not a plot, just a collection of images portrayed as a sequence of events. It’s curiously reminiscent of the poem that Howard first wrote about Conan, which is also a blank story about mist and little else.

After a hundred and fifty years, what eventually emerges from this mist is the shape of the show that we just watched. That’s an interesting process.

Bierce anchors us to the Civil War, when Carcosa was obviously the poisoned aftermath of the War Between the States. Then Carcosa became something else with Chambers, then something else again with Lovecraft, and now with True Detective all those meanings are simultaneously extracted and meshed.

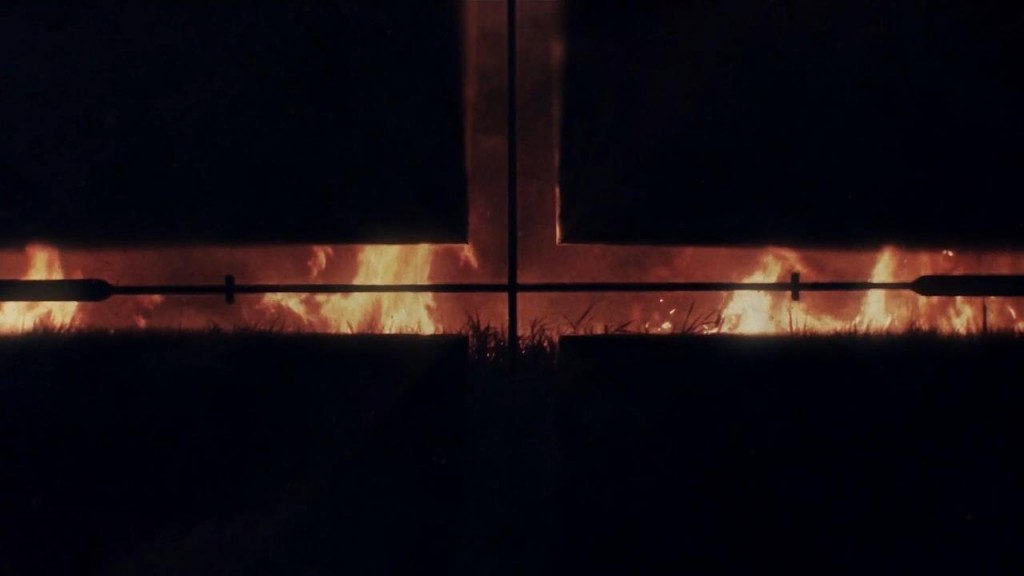

Nowadays Carcosa sounds like “carcinogenic,” which may be the point of oil refineries in the background everywhere and the “twin suns rising over the lake” at the end of episode 3:

Along the shore the cloud waves break,

The twin suns sink behind the lake,

The shadows lengthen

In Carcosa

By the way, there’s an oil refinery back behind that low rise.

“An owl on the branch of a decayed tree hooted dismally and was answered by another in the distance. Looking upward, I saw through a sudden rift in the clouds Aldebaran and the Hyades! In all this there was a hint of night — the lynx, the man with the torch, the owl. Yet I saw — I saw even the stars in absence of the darkness. I saw, but was apparently not seen nor heard. Under what awful spell did I exist?

I seated myself at the root of a great tree, seriously to consider what it were best to do. That I was mad I could no longer doubt, yet recognized a ground of doubt in the conviction.” — Bierce

I’ve yet to read Kierkegaard, and it’s only the influence of something as good as True Detective that could make me even want to. I’ve never been one to study philosophy. So, for this next part I have to lean on a different internet commentator called The Last Psychiatrist, whose article on True Detective contains some useful hints. TLP doesn’t really get TD either, but they were in conversation with yet a third internet commentator, who goes by the unlikely name of Pastabagel, and it is that which I excerpt here:

According to Kierkegaard, this resignation to the eternal is crucial. Kierkegaard was not an atheist but a diehard Christian. He believed that when a man resigns himself to the eternal, to existing in eternity, and gives up everything that ties him to this world then he becomes a “knight of faith” capable of great Christian acts (like the self-sacrifice that is almost certainly coming in ep. 8). When Kierkegaard wrote about a Knight of Faith, he contrasted the Knight of Faith to the mere Knight of Infinite, the “God botherer”–a phrase used twice in the show. What did Kierkegaard say the Knight of Faith looked like? Like this:

Why, he looks like a tax-collector!” However, it is the man after all. I draw closer to him, watching his least movements to see whether there might not be visible a little heterogeneous fractional telegraphic message from the infinite, a glance, a look, a gesture, a note of sadness, a smile, which betrayed the infinite in its heterogeneity with the finite. No! I examine his figure from tip to toe to see if there might not be a cranny through which the infinite was peeping. No! He is solid through and through. His tread? It is vigorous, belonging entirely to finiteness; no smartly dressed townsman who walks out to Fresberg on a Sunday afternoon treads the ground more firmly, he belongs entirely to the world, no Philistine more so. One can discover nothing of that aloof and superior nature whereby one recognizes the knight of the infinite. He takes delight in everything, and whenever one sees him taking part in a particular pleasure, he does it with the persistence which is the mark of the earthly man whose soul is absorbed in such things. He tends to his work. So when one looks at him one might suppose that he was a clerk who had lost his soul in an intricate system of book-keeping, so precise is he.

Yes — you are reading an essay that references an article referring to an internet conversation that quoted Kierkegaard. THIS IS WHAT PROPER ATTRIBUTION DOES TO PEOPLE. Just stealing everything is so much easier.

Back to True Detective. TLP pointed out that Pastabagel nailed it that Pizzolatto was taking Kierkegaard and bringing it to life. This may even be true.

It’s certainly intriguing that Rust is known as “The Taxman” and finds Childress by….searching tax records. It seem to me to be a fairly well informed conjecture that Pizzolatto was trying to bring the Knight of Faith to life, which makes it all the more interesting that Rust has a pronounced limp.

This ties into the most explicit “literary” allusion I’ve found yet. Erroll Childress is obviously the ultimate God Botherer — really, he bothers everybody, but in the final confrontation in Carcosa, as he has Rust spitted on the point of his knife (and what kind of knife? I’m sure if I knew it would contain some important detail), he said, “Take off your mask.”

This is of course a terrible mistake, because in a world where the ideas behind the King In Yellow are real there is only one response:

From Robert Chambers’ “The King in Yellow”

Camilla: You, sir, should unmask.

Stranger: Indeed?

Cassilda: Indeed it’s time. We have all laid aside disguise but you.

Stranger: I wear no mask.

Camilla: (Terrified, aside to Cassilda.) No mask? No mask!

Rust wears no mask. He is in the world, and of the world. He lives a life unsheltered. Errol wears nothing but masks. Every time you see him he looks different, talks different, acts different. He is a powerful but shattered mind. Rust, on the other hand, knows exactly who he is.

So he wins. And he wins like he usually wins; by using his head. In this case he uses it to head-butt Childress a bunch of times, but it still counts. Rust’s the Big Head, Marty’s the Little Head. Even here we are in symbolism.

Shelter and Logic

Note cross hanging above Marty, straight line dangling above Rust.

This sets up something important, deep, clever, and eminently doable. One of the main things I’m looking for in this analysis is stuff that is possible. Some things can be done, some things can’t. I’m interested in the story that springs de novo from this document, yes, absolutely, that’s my favorite part. I love to see the machine run.

But I’m also a technician, and I have a technician’s interest in the show. What is it that they did — that they could do — with their show to gets the story across in another way?

Well, here’s one thing. The show sounds like it’s dismissive of religion as “two sticks crossed together” but the show does not actually agree with itself on this question. Religion is depicted as arbitrary and inane but still helpful and useful. The bird traps are a demented form of the narratives that we us to get through our lives. The comforting shelter of narrative is fundamentally wrong but still fundamentally quite nice. It’s strange.

So the show’s an atheist’s show, sure, but it’s a critique of atheism too. If the show is fundamentally on the side of anything, it is on the side of doubt.

The shelter of religion, family life, social life, all the little lies are often depicted as a triangle.

The brute linear nature of logic and true perception of cosmic horror is depicted as a straight line.

“Translation of fear and loathing to an authoritarian vessel; that’s catharsis. He absorbs their dread with his narrative. Because of this he is effective in proportion to the amount of certainty he can project.”

Why yes it is, Rust. That is exactly what this show does.

This is not impossible to do! Let’s say you’re making a movie about two people who have a lot of quasi-religious conversations and you want to add a visual layer to the dialogue. You don’t need CGI to make this happen; all you need is a couple tent poles.

Marty is sheltered. He’s inside the structure/trap/framework depicted by religion, of which the bird traps are a primitive, debased echo.

It’s interesting that the show connects evil and debauchery to nature, barbarism, primitivism so often. These men that they chase are evil precisely because they continue to carry out their debased rituals thousands of years after they should have ceased, in a modern world that has no place for them.

And it’s also interesting that the revival church is depicted as a fairly positive place. I thought it was sinister that so many of their symbols appear throughout the story, but it turns out that it’s just the sort of story where symbols are everywhere and the preacher is one of the smartest, best people in the show. Why those nice young gentlemen even help their car get out of the mud they’re stuck in.

And later in the episode Rust meets Marty (with his red Volvo family station wagon)

Later, in 2012, Marty has his moment of brutal self-honesty in his office:

Strangely, at this moment, for the first time in the show Rust gets to dream a little bit.

Logic says there is no shelter, not really. Shelter doesn’t care, because it’s nicer inside.

The bird traps are of course the same thing:

There’s nothing wrong with this! There’s definitely something wrong with cults sacrificing children, but stacking sticks together in an attempt to make life more bearable is entirely a laudable pursuit.

“I always thought it was something for children to do. Keep them busy. Tell them stories while they’re tying sticks together.”

Childress, Carcosa and the Yellow King

Dolls with broken faces.

Creepy pictures of his grandmother, inbred girlfriend/sister cooking breakfast for him.

Later they have gross old/ugly/fat/incest sex, which I’m sure Western society can agree is practically the worst sex.Also, notice that practically everything in the background is doubled.

He even has this awesome lair.

Oh, that? That’s not his real lair. He has an even cooler lair than that. That’s just the spare lair where he keeps his dad tied to a bed so he can torture him to death (or maybe he’s already dead, but based on the fact that you can see a pulse on him while Dora Lange looks really, really dead implies that this show will give you a corpse when they want you to see a corpse).

THIS is his awesome serial killer lair:

I’m sure you’ll agree that in depth and breadth this guy is the champion murder-monster of all mankind. Errol Childress, inbred spawn of a Southern Gothic Murder Family/cousin of a Very Powerful Politician, is all serial killers at once. He even has an awesome serial killer theme he whistles as he searches for his (young, defenseless) prey.

Some commentators have pointed out, and I’ve yet to thoroughly prove it myself but it checks out so far, that Childress is the only person called a “monster” in the story. This is in spite of the fact that the story is chock full of child-rapist televangelists, methheads who kill babies, cops who cover up terrible crimes, biker gangster home-invaders, and inbred cousins who cook meth and LSD apparently out of orphans. They all qualify as monsters, but only Childress gets the title. He’s the Monster. He gets to wear the scary mask.

So Childress is the most imaginary of all imaginary monsters. He does it all. He’s a loner, he’s a cult, he’s a nobody, he’s related to the Governor, he preys on children, he fights adults with a tomahawk, he follows a code known only to himself, but he kills his dog with zero hesitation.

Childress is more Hannibal Lecter than Buffalo Bill, as Thomas Harris would be the first to point out. He’s not a real person, but an amalgamation of things we have seen in scary movies. For Rust Cohle’s Big Case he gets to fight the Encyclopedia of Serial Killers, and if Childress made a bird trap for every person he killed he’s one of the most prolific monsters since Dracula. There are many crazies in the world but he is not one of them, he is a creature directly from the imagination. Unlike the traditional meth lab/sex slave operation of the LeDoux compound, this thing has scope and range. He is the end of all serial killers, and the writer writes him like he never plans to write another one so he wants to get it all done this one time.

I respect that.

I hope you follow what I’m saying about symbolism here. I’m not saying that they’re using symbolic language to tell some impossibly complex story about bad-ass serial killers at a literary frequency that only neckbeards can hear. I’m saying they’re using really simple and universal symbols to make their story far, far more intense than it has any right to be. In lesser hands Erroll Childress would be just another movie monster. He wouldn’t be scary, he wouldn’t be deep, he wouldn’t make you think about life. He’d be just another guy who hangs out in a lair and provides entertainment.

By actually doing their jobs as artists and creators, by actually doing everything they knew how to do and doing it extremely well, the story becomes so intense that it vibrates into the fourth dimension. This may well spell the end of a genre, because True Detective may have been The Serial Killer Movie To End All Serial Killer Movies. There are two basic types of genius HBO TV shows; those that look back, and those that look forward. Those that close the door on a ending genre, and those that frantically carve out a new one. You can call them “Sopranos” and “Deadwoods.” This show is probably a “Sopranos.” After this, Se7en clones may seem a little more silly.

But this show may be something more. True Detective appears to be of equivalent depth to the Sopranos, and in far less time.

Of course, the ending of the Sopranos was bette

1995.

On the right side of the frame, over Rust’s shoulder, is the room where they will be interrogated in 2012.

The television is a nice touch.

Film School

So this town generates a certain number of five-star chefs every year. Some of them go on to five-star establishments, which means they leave this town. But a lot of them stay here and use their five-star knowledge on slightly less lofty things. That’s where Torchy’s Tacos came from; a guy who could have done anything in the world but chose to stay in Austin. All of a sudden, Austin has much better tacos. Presto, the power of education.

Film school is something like that. There’s a lot of film departments all around America, and they’re churning out a lot more PhDs in film than Hollywood is hiring. Oh, Hollywood’s pleased to take the cream of the crop. But most of the graduates go out as emissaries into the regular job world, and as a consequence the level of film literacy and image literacy in this country is staggeringly higher than it was fifty years ago. Check out any old movie for countless examples. It’s not that old movies are bad, it’s that they couldn’t begin to do things the way we do them now, and their audience could never accept the way we do things now.

Over the years there’s been a group of people in the film community who have developed a sort of symbolic language of film, using several consistent techniques. Art films of the 1970s, music videos, careful synthesists like Kubrick, and transcendental yarn-spinners like David Lynch have created an effective meta-language of film and film analysis.

A lot of it has to do with color. It’s a big thing with this crowd to really control the colors appearing on the screen, to make them as isolated and clear as possible. Pick any frame from any Kubrick film and you will be presented with clear, strong color shapes.

This has been going on for a long time and it’s not a conspiracy, it’s just a thing that people that make movies do. It probably makes the movie a little better, it certainly makes the movie more interesting for everybody else who went to film school and learned that language.

I guess you could call it a movement, it’s more like a thing that a lot of people have decided is a good idea. Somebody should probably coin a name for it, “colorists” or something. Movies like We Need To Talk About Kevin are definitely made by somebody who understands this stuff. I have no idea who made that movie, and it wasn’t that great of a movie. But it was carefully designed by somebody who understands this system fluently and speaks it well.

True Detective is such a fantastic expression of this language that I’m overcome with joy. I’m geekin’ out hard here, man. True Detective is speaking this language, and it’s speaking it well. It doesn’t matter exactly whether or not you agree with the “Ancient Indian Burial Ground” interpretation of The Shining, it’s obvious that True Detective is made by somebody who agrees.

Presto, the power of education. They have made a TV show that fluently speaks this meta-language that the film community has been developing for the last fifty years. Hooray!

Well, I think it’s great.

So what purpose does it serve to make a film that tickles the funnybone of guys who watch too many movies?

Well, one of the reasons is actually mentioned right there in the series. Catharsis. See, we the filmically overeducated can’t enjoy the normal shows quite the same way any more. We’ve seen too many, we’ve worked on them and we’ve seen them from the inside, and our relationship to the thing has changed. Can’t get the same high.

But you come along with a show like this, one that’s selling its story to the very smart, and it makes us feel like kids again. Here comes catharsis, as unerring as a proton torpedo.

And to promise this every week for eight weeks and then deliver? That, my friends, that is a gift. That is a very nice present that they have given us.

I’ll return the favor by doing my part, and geeking out.

So I’m not saying that there is a secret story that can only be seen by those who have been to film school. True Detective is a movie like Full Metal Jacket, where the symbolic meta-story pretty much tells the same story as the regular story. Think of it as music with great lyrics, an awesome bass line, and a wailing guitar solo, and you’ve just about got it. Yeah, classically-trained guitarists might get more out of the second solo to Layla, the slow one with the slide, but that doesn’t mean we can’t all enjoy the song.

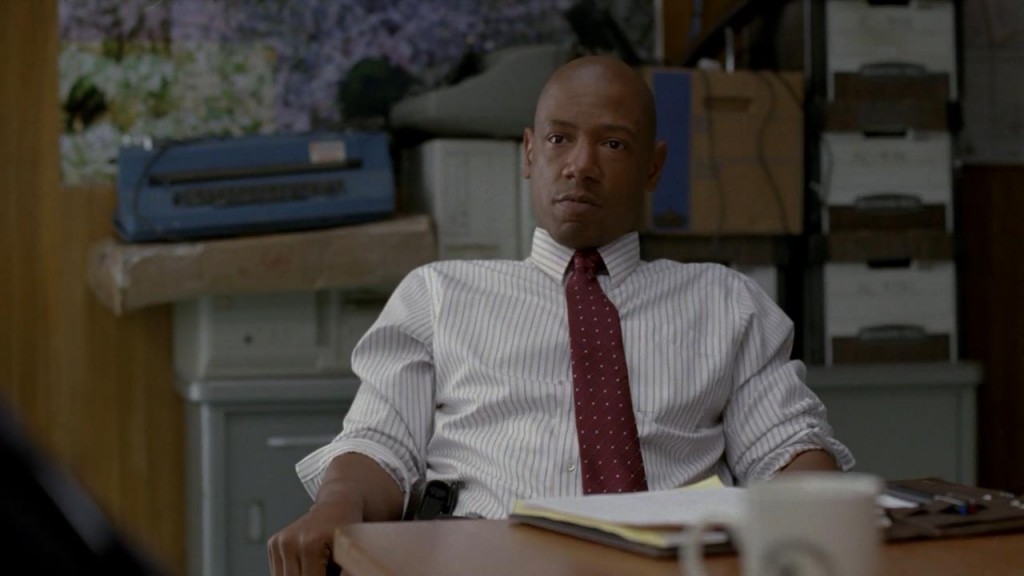

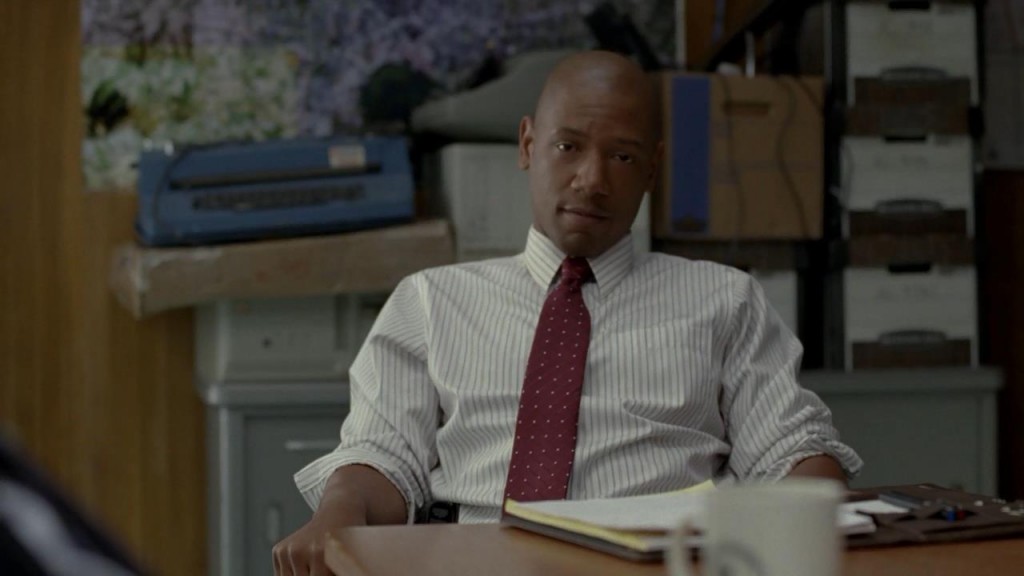

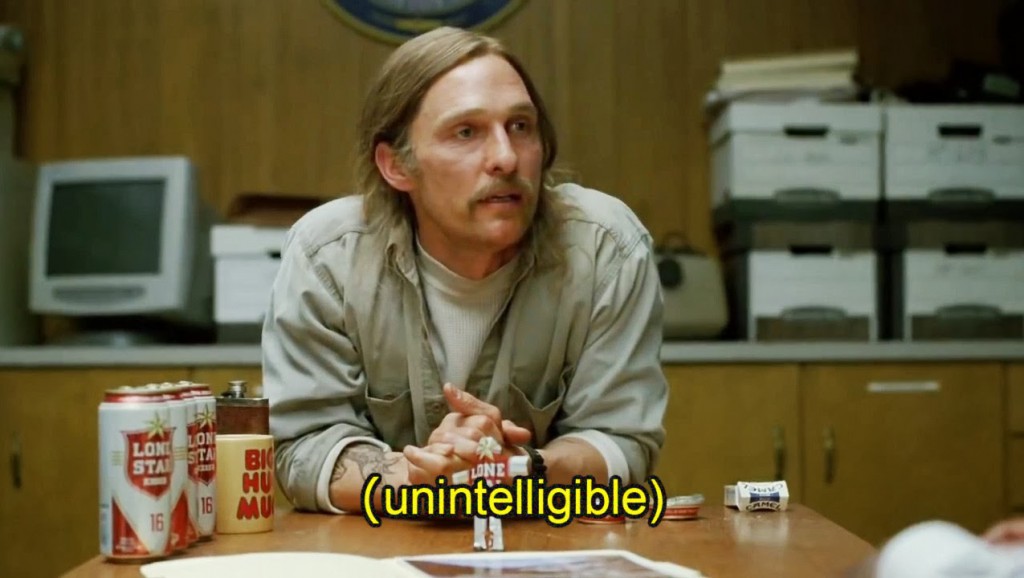

One thing I’d been noticing is this lavender patterned map that appears behind Detective Papania whenever Marty says something stupid.

I mean, obviously the map is always there, but there are only certain shots and angles where they show it. It’s very precise indeed.

Here’s where I display my True Scholarship, because I went through the whole show and screencapped every single time that map appears behind Papania (the younger detective). Here they are, along with what they were talking about when it happened:

After Hart asks them what’s going on with Cohle Papania says, “It’s alright, we just heard some stories.”

Hart: “My dad, I had about six inches on him, and even in the end I still think he could’ve taken me.”

Listening to Hart say, “You know what I mean…you gotta decompress before you can go being a family man.”

In response to Hart asking if they want to hear about the raid on LeDoux’s, Papania says, “Eventually, sure. Right now we’re just trying to track the case.”

Notice Marty starts to intrude on the shot.

That’s the last time you see the map in Marty’s interrogation. The next time you see it is towards the end of Cohle’s interrogation, when Papania and Gilbough decide to reveal to him that he is their suspect.

Episode 6 (the last interrogation episode, in which it becomes clear that they think Cohle is the killer) has some interesting stuff to say about this purple map.

Back in 2002:

This scene sent me down a rabbit hole of speculation. No, that’s not the same map as in the room. But it’s close enough, close enough that they would have had to have tried to get a map that was similar but not the same, and it’s not there in 1995 or 2012. Remember that this is the first time that we see the 2002 storyline. Also notice the orange-suited invisible man in the shot — I’ll have more to say on that subject soon. But this here is the frame that really tied something together for me:

I started looking through this particular combination of Papania and map with no clear idea what I was going to find, but I’ve noticed certain themes recur, over and over again, with that map. And with this frame four major story elements that I’m finding over and over again with this map appear:

1. Black cops versus white cops.

2. Taking people for granted.

3. Overlooking something important.

4. Hurting people’s feelings by accident.

Let’s get one thing absolutely out of the way. That map is not on the wall there in 1995 or 2012 — it’s there now, in the 2002 set. It’s only in this shot, the 2002 station only appears this one time and that wall only appears in this particular single set-up. That actor, who is nowhere else in the series and the only black actor in this scene, has been instructed specifically by the director to go walk in front of that map, stand there long enough for them to deliver one line, and then leave.

That map is not the same map on the wall in the interrogation room, but it is so close as to be indistinguishable — they had to find a map that was almost but not the same. This is not an accident. That map is part of a visual motif, and an important one.

Let’s proceed without the endless arguments of whether or not set designers put things on walls on purpose. Of course they do. That’s their job that they get paid to do.

This is not a sign of a long-ranging conspiracy or anything within the story. This is the background reacting to the foreground. The map appears — which is to say, the set is dressed and the shot is framed so that the map appears — when the person driving the action in that particular exchange is overlooking something important because and losing essential detail in the pattern. That map was not put there by the Illuminati.

I’m sorry, and I’ll tell you, if you made a TV show where that map was put there by the Illuminati I would watch the hell out it. But it hasn’t happened yet and it is not this show.

Now’s a good time to mention, once again, how closely that map resembles a floral pattern.

(and by the way, the next scene after Marty and Rust fight over the report is the one at the mental hospital, where the flowers from Marty’s bedroom appear on the hospital wall)

Last scene in the police station, last scene in 2002, the interrogations are over, the map does not appear again.

SO WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?

Well, let’s review. Scroll back up to the top and look through the screencaps again. Remember that I’m not claiming any privileged knowledge here, I’m only watching the show, just like you. I’ll remind you of one thing, though; there are a million shots of Papania in that interrogation room, and the map is there for all of them. These are the only times that it appears. I have exhaustively sorted through the whole series to save you the time. If I missed one, send it over and I’ll add it in, but I don’t think I missed one.

I think the fact that the files and boxes are stacked over the map in Maggie’s scene symbolizes how completely she is a dead end in their investigation.

I think the fact that the map does not appear in Rust’s interrogation in any meaningful sense (it’s even darkened when they walk by it) is because Rust does not take these men for granted. These men do not blend into the background at all. They are his students, and his adversaries.

Rust never says anything even vaguely racist, as opposed to Marty, who is a big one for saying casually racially insensitive things and then rolling his eyes when someone gets annoyed:

It’s hard to say whether certain lines were filmed a certain way or if he happened to sit a certain way when saying certain lines or what….it all combines together into the story as we see it, and what we know is that when a character appears in front of a floral background the detective in question is not really seeing them. And a lot of them know it. Here’s the scene that made me start to suspect what was going on:

Marty: “My dad, I had about six inches on him, and even in the end I still think he could’ve taken me.”

Why is he so pissed?

Because, issues of fatherhood and legacy loom in this character. And, for some reason, hearing this old white man measure penis size against his father, who was probably even more racist than he is, really seems to annoy Detective Papania.

Legacy

Let’s look at this show as an expression of the monster-slaying myth.

This here is a generally excellent essay that expresses a really good point:

Marty is Ariadne, Rust is Theseus, Childress is the Monster, and Carcosa is the Laybrinth.

It’s close enough that it works, and it may even be on purpose. After all, it’s been on the radar since House of Leaves, why wouldn’t they take the next step here? Maybe it’s just a general blueprint for monster-fighting.

So Cohle is Theseus entering into the labyrinth to slay the monster, Hart is Ariadne who provides the clues to get in* and the path back out again**.

*While watching the show for these essays I’m struck again and again by how tenuous the thread of leads they follow is. They get precisely one clue per scene, and it’s always at great effort. Don’t hold me to this observation yet, but I’m pretty sure that if you had subtracted even one of their sordid Louisiana interactions they would not have been able to Solve The Case. This makes sense and is a fairly easy way to write, because they’re telling the story backwards and recounting the exact trail of clues that led them to Carcosa.

**After slaying The Monster Rust says, “We didn’t get them all.” “No,” says Marty, “But we got ours.” And with that he lays a path back out of the Labyrinth. Rust can escape. Check that essay I just linked to as a good extrapolation along these lines.

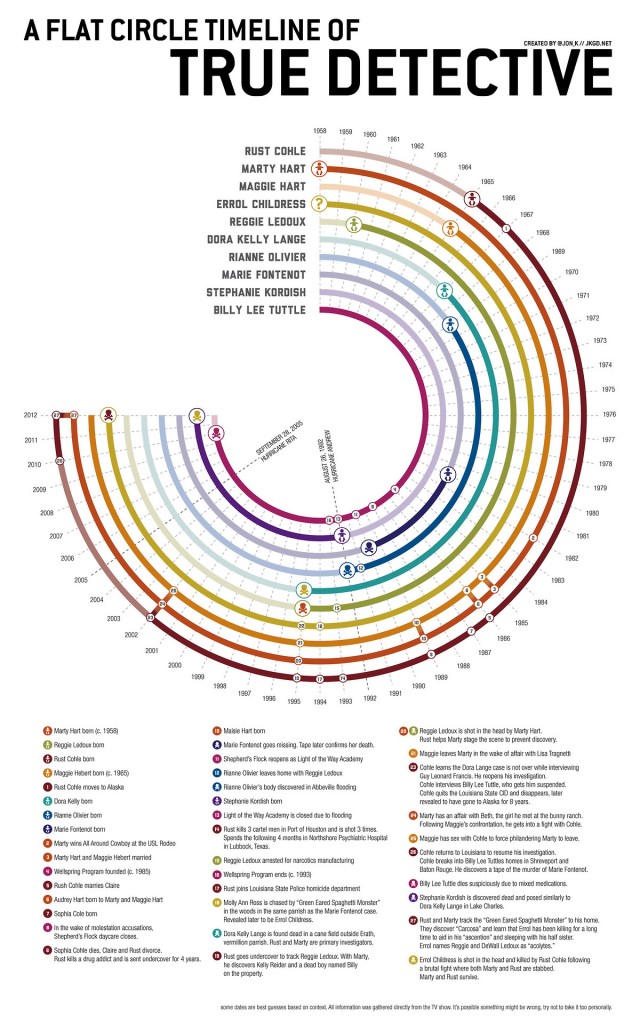

The point of the Minotaur myth — of any myth — is that it happens, over and over again, amongst all aspects and all realities. Time is a flat circle or something, sure, I guess, but with that knowledge comes the need to train replacements, because everything’s gonna happen again. There are monster-slayers who came before these two, and those who will come after. It will be Papania and Gilbough’s turn next in the long line of honored pictures on the storeroom wall.

One of the cool little mini-meta-stories of True Detective is the way that the police department evolved. You can see this in the commander, going from screaming Captain Quesada in 1995 to Captain Lou Shoutydude in 2002 to their old buddy as the new Captain in 2012. Another major point they make is that there are a lot more black cops. In 1995 there are no black cops, just a lot of pasty white guys like Steve Geraci. In 2002 you start to see black cops appearing, as I demonstrated, out of the background.

2002: As Rust leaves the station for his appointment with the reality of flowers he walks around the black cop who had been standing in front of the map.

And now in 2012 the new detectives are on the block, and Marty and Rust take the trouble to school them.

Papania and Gilbough are both younger than the men they’re interviewing, though Gilbough is the older of the two. Gilbough is quieter, more inscrutable, apparently deeper. If one of them is into the occult it’s him, he’s the box man, he’s the mystic. I try to avoid looking for cute name references, but Gilbough’s name is close enough to “Golden Bough” that that’s how I remember how to the spell it. Papania’s name, I don’t know exactly what it means. It has the word Papa in it. I know that he has three kids, that he’s still married to his first wife, and that he appears to have father issues.

He doesn’t like Marty’s casual racism, and Marty’s casual racism is highlighted several times. I know somebody can tell you say exactly what kind of racist Marty is, but I’m not qualified. I just know that he’s this one particular type that I’ve met a few times. The “regular guy” type….he’s not actively racist, but he has a lot of weird little racist tics and he doesn’t think a thing about it. Check out the scene where he returns in 2012 to talk to the new captain:

Hart: “A pilot, you racist bastard. What else would you call them?”

Ta da! The official non-racist joke of racists.

This joke’s told over an establishing shot of the new office, in which you see a black guy working as he tells it. True Detective is making a point here. Cops in 1995 were casually racist. 2012 cops are a lot less racist, and a lot more sensitive about it, and Marty’s out of place and out of time. Things are changing. The black detectives have emerged from the background, and resent being overlooked — being forced back into the background. Like Marty resents being forced into the background.

And by the way, that clock says 4:20.

So, all these floral patterns in the show? Maybe they represent the people that the detectives only as background, as simple flowers on the path of their life, to pick or cut down as they choose.

Maybe it’s because when you look at them too long, patterns all blend together, and it’s only the solid colors that stand out. But patterns are made of solid colors, aren’t they? You just have to focus on their level.

When Rust goes to visit the girl in the hospital, that’s when the flowers snap into full focus. Here, for the first time, Rust confronts the consequences of his action and inaction, attention and inattention. The girl he saved? It turns out that he never saved her, not really. She’s not okay. She never got the help she needed.

The people in floral patterns in this show….this is a good time to remember something. This show is from the point of view of the characters, or Hollywood, whichever you prefer. The point is that everything is prettier, handsomer, more dramatic, clearer. This is a movie that is very much from the point of view of the main characters, and that means it is they who clothe these people in floral patterns. It’s Marty who thinks his daughters match the wallpaper. His daughters most certainly do not agree.

There are a lot of people in this show who blend into the background (try to find a shot in the office in 1995 that doesn’t have an orange-suited prisoner doing menial work somewhere in the back). All this talk of flowers in the series, all the pictures, I think this is what it’s about. Flowers are inanimate objects. Flowers are there to look pretty. They don’t think anything, they just grow. They are indistinguishable from each other, they simply each grow according to their nature. Some people seem like flowers to them. But the flowers hate them, because the flowers are really people.

When the Monster makes love to his sister, he “makes flowers on her.”

That’s pretty deep, right? That seems like a pretty brilliant comment on the mentality of highly focused alpha males to me.

How do people think of this stuff? How does anyone come up with little tiny background stories like this, to enhance and illustrate the foreground so brilliantly. And that’s why there’s the strange and jarring touch of the children’s flower drawing suddenly writ large.

If this stuff is not really in the film, if this is just my imagination, then I am so dang proud of my imagination. And if it’s not really “there,” then it’s like I made it up, isn’t it? So you won’t mind if I use it in my own work.

And when you see it in my work, you can be sure that I am actually doing it on purpose.

Here is a favorite bit of symbolic visual language from True Detective. When Rust returns to the spooky school at the end of Episode 5, he finds weird paintings and sculptures everywhere. These three things are scrawled on a wall:

Doesn’t get much plainer than that, as set decoration goes.

Now let’s talk about what’s not there.

Hallucinogens

These are called “tracers,” and I believe that it is perfectly safe to operate a motor vehicle while experiencing them.

Again, these two are common experiences. They happen to practically everyone who tries any sort of hallucinogen and they have very basic physiological causes — for example, tracers occur because the irises of the eyes open, the motion of the eyes becomes different, and the way the brain processes the information alters. The streetlights don’t change, but the way you perceive them does.

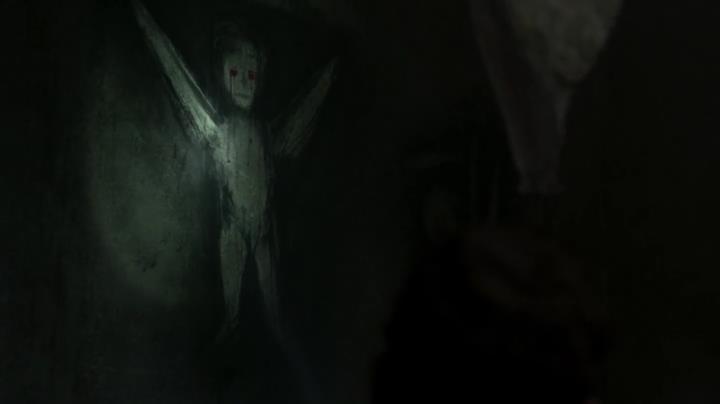

The vortex that Rust sees is quite unusual, true, but it’s also true that when taking extremely heavy shamanic medicines you can see very convincing things for a second, only for them to instantly disappear when you’re distracted (by a bump in a road or a door opening or a giant maniac attacking you with a tomahawk and a knife at the same time).

So let’s dispose of a few things here.

1. Two of the hallucinations are meaningless from the larger story standpoint, they’re there to let you know that Rust has done some hallucinogens (and so have the creators).

2. The spiral is Rust’s brain’s way of letting him know he’s on to something. A particularly beautiful symbol, where all the various birds from the interviews (see later in this article for details on the birds) assemble themselves into a coherent pattern. That is the sort of thing that you could see on hallucinogens, but it would be unusual, cool, and quite memorable. Just like in the show!

3. The vortex was not “really there,” and that’s why Marty didn’t see it. It was probably a “consensual hallucination.”

This is one of my favorite parts of the show, because I’m used to TV getting hallucinogens wrong. But this….this is something that could almost happen.

Maybe Rust, whose eyes are permanently opened to this sort of thing, saw something which many people who have been to this exact spot have also seen. People including the old secretary, Miss Delores:

Miss Delores: “You know Carcosa?”

Cohle: “What is it?”

Miss Delores: “Him who eats time. Him robes. . . It’s a wind of invisible voices.”

Dora Lange probably saw it:

Reggie LeDoux probably saw it:

Reggie: “I know what happens next. I saw you in my dream.

You’re in Carcosa now. With me. He sees you.”

Let’s wonder if what Rust saw is what they saw:

It’s not “really” there. It disappears the second he’s distracted. But maybe it is “really” there, in that other people have seen it, over a large amount of time. I’m reminded of Grant Morrison’s excellent book Supergods, where he points out that yes, Superman and Batman are not real. But in another sense, they’re actually more real than he is. More people know them. More people care about them. They’re older. They have specific life histories, specific personalities, specific modus operandi. They will still be around long after Grant Morrison and everybody who ever knew him are crumbled to dust. In some ways, they are actually more real than their creators.

Maybe the vortex is “there” in a consistent fictional sense — as a tulpa, or a ghost, or a something, or whatever you want to call it. The point is that many people have seen it and not known what they have seen.

This is about religious experience. Even if you’ve never seen God, you know that people have. They may not have in the scientific and rational sense, but in a real and memorable way that is real to them. And the same goes for Zeus and Thor and UFOs — they may not be “real,” but we know that people have seen them as if they were. Maybe behind our little stories is the occasional true fiction. Maybe our myths are shadows cast by something that stands outside of our perception. A lot of people would say “other dimensions.” I don’t believe in other dimensions, so I hate to go there, but you could sure call it that.

Maybe the vortex is a personal “god” that has been seen by many hallucinogen-addled people (and hallucinogens are far, far older than LSD) who have been in that particular room worshiping at that particular altar in a wide variety of emotional states, and many have died in that room too. Whatever energy there is in the human mind and human heart has been repeatedly harvested to feed/create/make contact with that thing, and even if it’s not real enough for Marty to see it’s real enough for Rust to see.

But it’s not “really” there. It’s a hallucination, maybe shared, maybe not.

Let’s talk about other things that may or may not be there.

Spirals

Spirals are everywhere in this show, and I mean everywhere.

You see that spiral on the wall of Marty’s home? HE DIDN’T EVEN KNOW IT WAS THERE.

Neither did the writer, director, or set designer. They just got a bunch of kids’ drawings and put them on the wall, and it just so happens that one of them was a spiral? Why?

BECAUSE SPIRALS LOOK COOL AND LOTS OF PEOPLE DRAW THEM.

It’s a basic human symbol. Here’s how you draw a spiral: try to draw a circle, fuck it up, but keep going. Pretty easy!

Look, he’s mowing the lawn in a spiral! He is not mowing the lawn in a spiral to show cult involvement, he’s mowing it in a spiral because that’s the most efficient way to mow a lawn, and that’s why they showed him mowing the lawn — because it fit in. They didn’t invent a new way of mowing lawns for True Detective. Rather, they used what was around that fit, and the better it fit the more they emphasized it. It’s a small but important distinction.

So spirals are everywhere, but they are not always a sign of cult involvement. They’re a shared idea that everybody working on the series had incorporated at several points in several ways. They’re not a clue, they’re not even a clew.* They’re a motif. They don’t point to anything** specific except the process by which the director and production crew made the movie. Never forget that, long before you get to see a TV show, it is a story that the creators tell to each other. When you remember that it helps to separate the things that are meaningful from the things that are, for lack of a better term, set dressing. You have to be able to separate the two. If you don’t, that way conspiracy theory lies, and that’s almost as bad as being blind. Seeing too much can be as distracting as seeing too little when what you actually want to do is to see the truth.

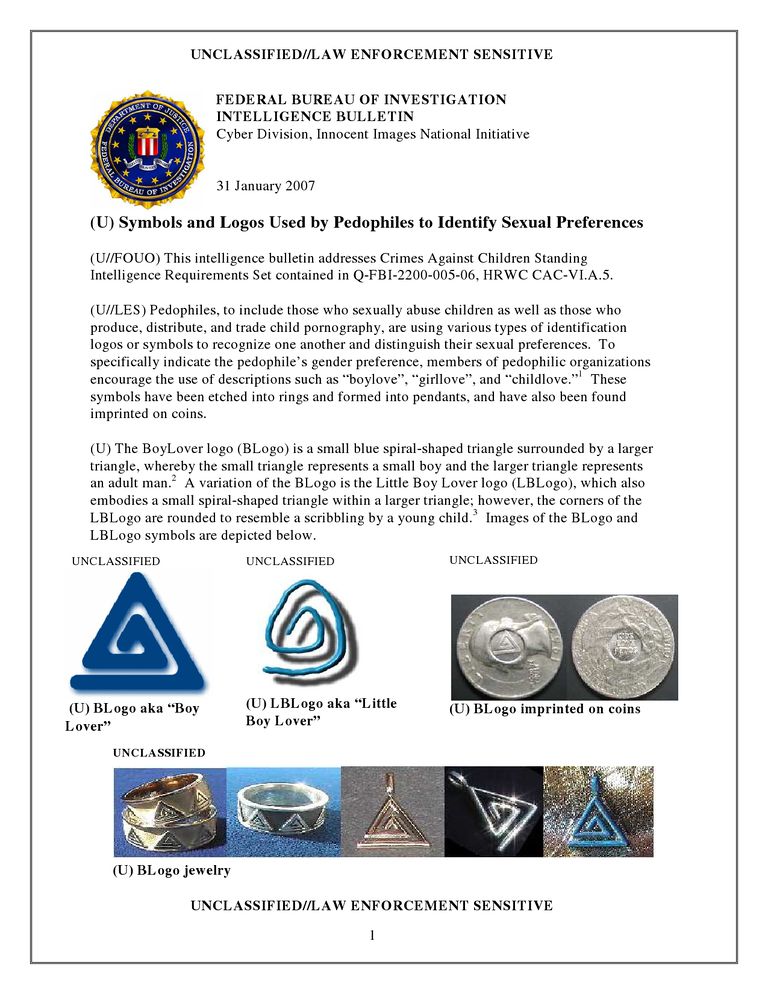

Here’s my favorite spiral:

This is from Wikileaks, and it is from 2007.

And let me just say how perfectly multifariously creepy it is that pedos call their nightmarish film company “Innocent Images.”

That’s horrible on at least three levels.

Look at the date. 2007. Look at the source; this is from the FBI by way of Wikileaks. This is real; this is a real thing done by real people in the real world, god help us all. Obviously Pizzolatto and Fukunaga did not invent this for this show. But I do wonder if they were aware of it. And either way you look at it, I thank them for bringing this to our attention.

Once again, it is the difference between inventing things, which is a bad way to do things, and using things you find lying around, which is a good way to do things. It’s bad to invent these things, because the human mind is quite limited compared to the totality of society and the things we make up always seem paltry and frail compared to the robustness of real life — read any high fantasy novel for a perfectly stultifying demonstration. It’s good to use things, because that attaches your story to real life, makes things bigger than they ever were. Instead of a pathetic ivory tower, your story is a bustling marketplace, where all are free to trade.

*I’ve been waiting to make that joke for about fifteen years, by the way.

**of course not, they’re spirals.

Patterns

You could call this sexist, for all the good it’ll do you. The point here is that it’s true. It’s true for the show, and it’s true for a lot of people who watch the show. This really is the way that manly-type men that you see on TV see the world and the people in it. It’s sexism in the same way that a doctor is the disease that they treat; sort of, but not really.

In real life women are people. But that is too complicated for this show and many of the men who watch it. In this show (and to many of the people who enjoyed the hell out of this show) men wear solid colors, navigate by patches of solid color. Women are complex, confusing, blending into the background, difficult to describe.

In this case the show presents both the doctor and the disease. Make of that what you will. It does this quite often. The binary pairing of ideas is actually one of the fundamental motifs of the series, and I challenge you to notice how many times two people are compared to each other, two ideas are compared to each other, or the screen is divided between two contrasting visual elements.

Whenever I look at this shot I think of that scene in “Babe” where the pig separates the brown chickens from the white chickens.

Let’s just agree that, by this point, we’ve established that certain things are there, certain things are not there, and we can sort-of tell the difference.

In and Out of the Crosshairs

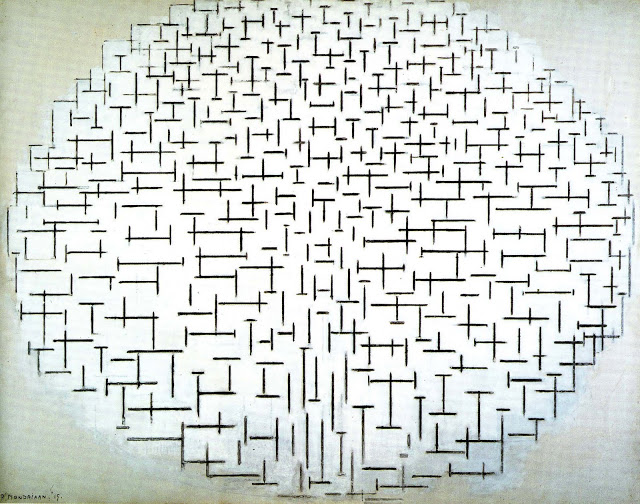

I borrowed this from my wife, Gewel Kafka:

Piet Mondrian’s used of vertical and horzontal lines was adapted after his visit to Paris in 1912 where he saw the work of the inventers of cubism, George Braque and Pablo Picasso. Over the next few years Mondrian would refine this grid that he borrowed form their work, simplifing his subject matter to its skeletal minimum: Verticle and horizontal lines. Unlike his cubists contemporaries that nearly saw the cubist grid as a means to portray the ether of reality by showing the transparencies of substructure, whether a line was horizontal or vertical, a plus or a minus, determined whether it was static low energy, or a dynamic high, and this held deep spiritual meaning, so that the act of composing a painting was a process of balancing the universe.

When she told me that, it was the first time that I really “got” Mondrian. It’s so simple and it’s so deep. Horizontals and verticals are fundamentally different. A vertical is a thumb in the eye of entropy, a horizontal is the natural state of mud. Verticals represent effort, activity, motion. There is no such thing as a cross, a perpendicular, a plus sign in nature. They are all products of our mind. But that doesn’t make them any less true. Here’s Mondrian’s painting “Pier and Ocean.”

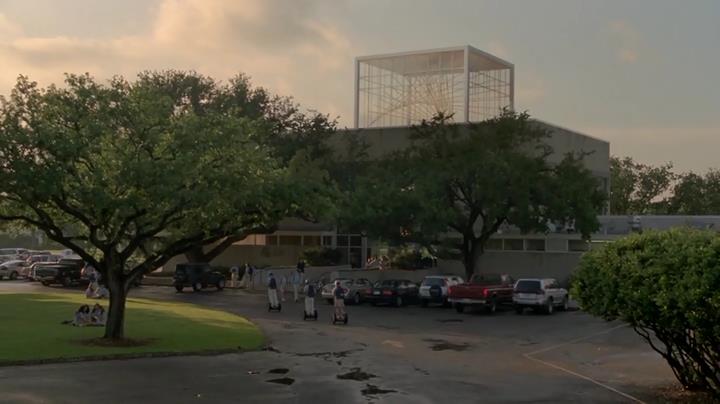

I don’t know if Pizzolatto or Fukunaga or anybody anywhere knows about this stuff besides my wife, and then me, and now you, but I find it fascinating and think about it all the time. There is so much going on in True Detective with straight lines and crossed lines and parallel lines; it’s everywhere. Here are two favorite examples, and then I’ll leave the rest for you:

I don’t know why that cross is reflected on his hood, but it sure as heck is. Maybe it’s because he’s out there working for Rust.

There are a lot of sly jokes in this picture, like the fake Hollywood puddles and the segway dorks, but look at that thing on the top of the building (and it’s definitely CGI). It’s a bird trap inside a box; it’s an endlessly over-refined lattice. You’re trying too hard, Reverend Tuttle, and you’re covering something up. I can’t believe they manage to get so much done with their straight-line language. Nic Pizzolatto must be a fair hand with a set of Lincoln Logs.

Crosshairs, parallel lines, bird traps, triangles, straight paths — I read somewhere that Chinese folklore states that devils travel only in straight lines, and there may be something to that — rays of light, abstraction, division — lines. Even Rust’s drawings are done in ligne claire style

Birds

Women are explicitly mapped to birds in this show. And I mean explicitly — every time a woman appears in the frame in the first couple episodes there is either a picture of a bird somewhere in frame or the sound of birds chirping. I’m leaning on the work of an anonymous internet commentator here: