True Detective: One Measures A Circle Beginning Anywhere

on April 15, 2014 at 0225There’s too much talk about what True Detective does and not enough about how it does it. It’s like a great song with great music and all anybody talks about is the lyrics. That’s the way life is, I guess.

There’s this moment, in episode 4, when Charlie Lange, the incarcerated former paramour of Dora Lange, the woman whose death theoretically sparks this investigation, reveals to our fearless detectives the name of a character of no importance whatsoever. This character is called Tyrone Weems, who will be in only one scene in which he will do nothing but reveal one more clue on the trail of the dreadful Reggie LeDoux. Immediately after Lange tells them about Tyrone, his name appears written on the wall to the left of the detectives.

That’s the kind of show this is. The show reacts to the characters, the investigation appears everywhere. The coincidences are so manifold that you start to think that Marty’s family must be victims of the cult at the center of the case or something, because how else could they know enough to say things like this:

Maisey: “You won’t have a mommy or daddy anymore. They’ll just die in an accident”

Audrey (presumably): “How?”

Maisey: “In a car accident. Somewhere.”

if they didn’t know about the cult?

How could Marty’s daughter be drawing things like this:

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_24.48_[2014.02.18_11.55.52]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_24.48_2014.02.18_11.55.52-1024x576.jpg)

if she doesn’t know about the woman with flowers on her? Heck, she’s only in the opening credits. Has Audrey seen the opening credits?

How could a child’s drawing on Marty and Maggie’s bedroom wall in 1995:

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_29.26_[2014.04.13_03.06.03]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_29.26_2014.04.13_03.06.03-1024x576.jpg)

possibly appear here, painted large, on the wall of a mental health ward in 2002:

![TD s01 (6).mp4_snapshot_24.37_[2014.02.26_01.49.09]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-6.mp4_snapshot_24.37_2014.02.26_01.49.09.jpg)

….and with that the conspiracy runs aground.

Okay, there is just no way. Shadowy government conspiracies abusing the daughters of cops, sure. Sinister cults that take kids’ drawings and turn them into giant institutional wallpaper patterns so that their parent’s coworker partner can seven years later (not) find them…no, I can’t buy that conspiracy. That’s Illuminati-level nonsense. This thing may go deeper than anybody knows, but it doesn’t go that deep.

But that doesn’t mean that the choice wasn’t made on purpose. It means that it was a purely symbolic choice. For whatever reason, this story wants us to think about those flowers and these flowers at the same time. The universe reacts to the investigation, the story reacts to the story. Time is a flat circle and everything happens, over and over again, on every level.

It’s an impressive performance. I’ve rarely seen a work that speaks this clearly on the symbolic level. That’s why I’m so excited about this show.

Let’s get this out of the way, because this applies to every element that we discuss. Did the writer “put” it there? Did the director “put” it there? Did the production crew “put” it there? We’ll never know. But it’s there now, and we’re discussing the film as it is, so let’s talk about it. We’re not trying to recreate a holy text, we’re figuring out how to use this stuff for ourselves.

I don’t care if every single time Marty stands next to a triangle-shaped arrangement of sticks is a wild coincidence, now that I’ve perceived it I can use this in my own work. True Detective demonstrates how symbolism can be deployed consistently and accurately when you tell a story. Now that we know how, we can all do it.

True Detective found a new way to look at sunsets, and then applied that knowledge to a movie about two buddy cops who hunt a serial killer. It’s that simultaneously revolutionary and commonplace.

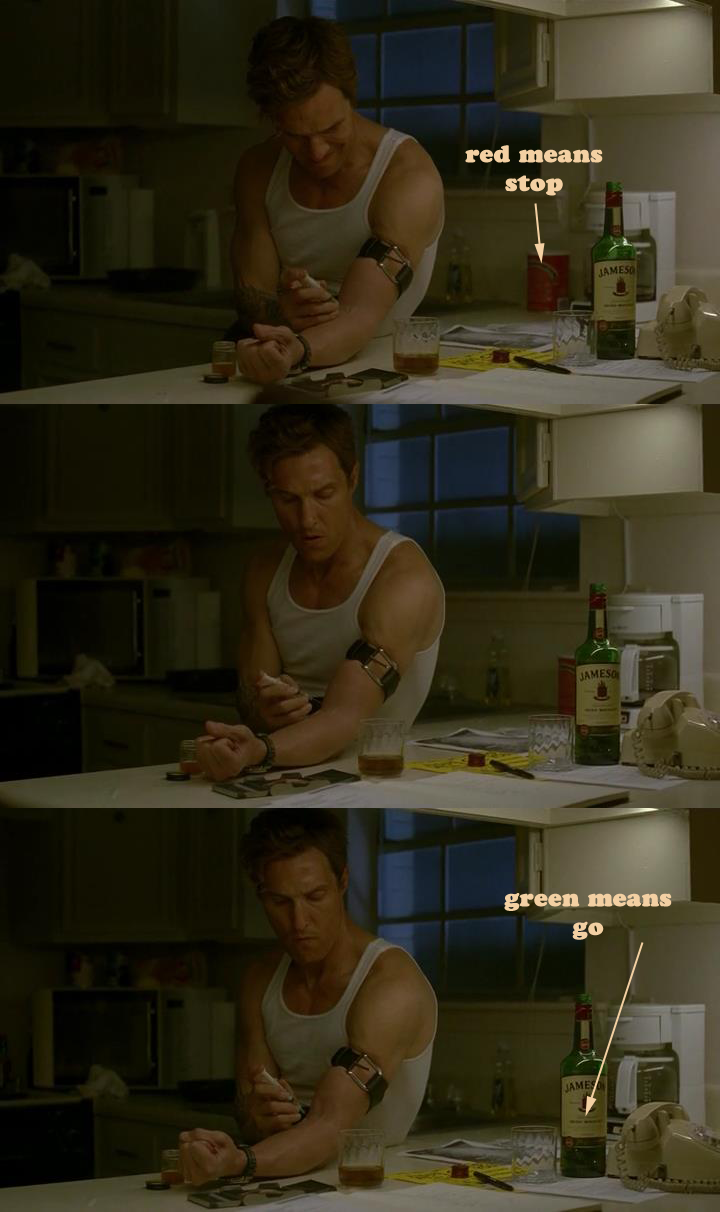

So now we know this thing is working on this level, we know to pay attention. For example, we know to pay attention to the color yellow:

You see that yellow blotch on the frame there? It’s not a speck of popcorn on the lens. It was actually added with CGI. Seriously. The creators of the film are expressing the symbolic language of this moment through a bright yellow mistake.

Much is made of yellow in this story. Much is made of many small things. True Detective is a very focused piece of craft. They want to evoke specific myths and fictional constructs through the lens of a perfectly genre show. So True Detective is exactly what it promises. It is the perfect noir cop buddy pic for the ages, and if that doesn’t sound good to you then you will not like it.

So, in the part of the article that you have read so far, I have blundered into at least three major areas of True Detective study and probably a few more that I’ve yet to notice. The three things that I keep returning to in this show, over and over, are:

1. Use of color and background to tell a coherent symbolic story.

2. Background detail that reacts directly to the story’s internal logic instead of external logic. The clearest example of this is, of course, when Rust sees the birds:

3. Awareness of narrative and the specific functions of specific narratives, from old cast-off weird fiction ideas like the King In Yellow or the Narrator Who Slowly Goes Mad to other delightful bits of folklore like the Prisoner Who Kills Himself After A Mysterious Phone Call and the Methhead Who Microwaves His Baby and the Hot Girl Who Was All Over Me And I Just Couldn’t Help Myself, because this all leads to the bigger picture; the lies men tell to justify adultery, the rationalizations policemen use for brutality, the way we tell stories to keep ourselves going on. And it culminates in Carcosa, in contact with an utterly alien consensual hallucination — that’s an interesting place for the story to go!

Until I realized that #1 is leading directly into #2, parts of this story were very confusing to me.

For example, the massive story-breaking coincidence of Marty meeting the girl he gave money to at the bunny ranch all those years ago at the exact moment that he decided to fall off the wagon and get a drink at a bar that just happened to be next door. It only makes sense one of two ways; if there is a story-spanning conspiracy by powerful figures to undermine him, or if the background reacts to the foreground. The latter is obviously true, unless you’re willing to come up with a story that answers why the governor of Louisiana wanted a child’s drawing of flowers to be found in both Marty’s bedroom and in the hospital ward.

Maybe this scene happens in an alternate universe where beautiful young women hit on bald men who can’t figure out their cell phones.

The truth is, and this truth would be obscured in a less carefully-created piece of fiction, the story reacts to the characters. Any particular creator may or may not have intended this at any particula moment, but this is the document that we have before us. True Detective is the record of the psychological reality of some imaginary people. It is not “perfectly realistic” and it does not wish to be. Rather, what we are seeing is the main character’s side of events. We’re seeing the story that the characters tell, not the events that led to the story. It’s a crucial difference.

Whether we are seeing the story that Marty tells himself to explain why he had an affair, or if we are simply failing to correct for the dramatic pressure that causes things in movies to happen too quickly and to people who are too pretty, it amounts to the same thing. Marty’s fall at the Fox and Hound is not a literal fall, it is a literary fall. This story revels in the fantasy that it all matters.

In this show they are selling one thing; that it all makes sense. That there is an underlying rhythm to reality, and by living in the right way and taking the right drugs and being a general desperate bastard you can perceive it. You can never control it and you can never, never understand it, but it is there and it can be seen. Sometimes. Sometimes, when you’re watching True Detective on TV, it seems like it all makes sense.

And of course that’s how it’s supposed to feel.

This is part one of a six-part series about True Detective. Here is the entire essay.

Here are the other five-and-a-half chapters:

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Six-and-a-half

![TD s01 (4).mp4_snapshot_14.28_[2014.04.02_04.39.45]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-4.mp4_snapshot_14.28_2014.04.02_04.39.45.jpg)

![TD s01 (4).mp4_snapshot_14.35_[2014.04.02_04.39.52]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-4.mp4_snapshot_14.35_2014.04.02_04.39.52.jpg)