True Detective: Papania and the Map

on April 26, 2014 at 0833This is part four of a six-part series about True Detective. Here is the entire essay.

Papania and the Map

1995.

On the right side of the frame, over Rust’s shoulder, is the room where they will be interrogated in 2012.

The television is a nice touch.

Film School

There’s a world-class culinary school in this town. They’ve been around for a while. Literally world-class, they train people to become chefs in five-star kitchens. But, until recently, this was not a town with the money to support any five-star restaurants.

So this town generates a certain number of five-star chefs every year. Some of them go on to five-star establishments, which means they leave this town. But a lot of them stay here and use their five-star knowledge on slightly less lofty things. That’s where Torchy’s Tacos came from; a guy who could have done anything in the world but chose to stay in Austin. All of a sudden, Austin has much better tacos. Presto, the power of education.

Film school is something like that. There’s a lot of film departments all around America, and they’re churning out a lot more PhDs in film than Hollywood is hiring. Oh, Hollywood’s pleased to take the cream of the crop. But most of the graduates go out as emissaries into the regular job world, and as a consequence the level of film literacy and image literacy in this country is staggeringly higher than it was fifty years ago. Check out any old movie for countless examples. It’s not that old movies are bad, it’s that they couldn’t begin to do things the way we do them now, and their audience could never accept the way we do things now.

Over the years there’s been a group of people in the film community who have developed a sort of symbolic language of film, using several consistent techniques. Art films of the 1970s, music videos, careful synthesists like Kubrick, and transcendental yarn-spinners like David Lynch have created an effective meta-language of film and film analysis.

A lot of it has to do with color. It’s a big thing with this crowd to really control the colors appearing on the screen, to make them as isolated and clear as possible. Pick any frame from any Kubrick film and you will be presented with clear, strong color shapes.

This has been going on for a long time and it’s not a conspiracy, it’s just a thing that people that make movies do. It probably makes the movie a little better, it certainly makes the movie more interesting for everybody else who went to film school and learned that language.

I guess you could call it a movement, it’s more like a thing that a lot of people have decided is a good idea. Somebody should probably coin a name for it, “colorists” or something. Movies like We Need To Talk About Kevin are definitely made by somebody who understands this stuff. I have no idea who made that movie, and it wasn’t that great of a movie. But it was carefully designed by somebody who understands this system fluently and speaks it well.

True Detective is such a fantastic expression of this language that I’m overcome with joy. I’m geekin’ out hard here, man. True Detective is speaking this language, and it’s speaking it well. It doesn’t matter exactly whether or not you agree with the “Ancient Indian Burial Ground” interpretation of The Shining, it’s obvious that True Detective is made by somebody who agrees.

Presto, the power of education. They have made a TV show that fluently speaks this meta-language that the film community has been developing for the last fifty years. Hooray!

Well, I think it’s great.

So what purpose does it serve to make a film that tickles the funnybone of guys who watch too many movies?

Well, one of the reasons is actually mentioned right there in the series. Catharsis. See, we the filmically overeducated can’t enjoy the normal shows quite the same way any more. We’ve seen too many, we’ve worked on them and we’ve seen them from the inside, and our relationship to the thing has changed. Can’t get the same high.

But you come along with a show like this, one that’s selling its story to the very smart, and it makes us feel like kids again. Here comes catharsis, as unerring as a proton torpedo.

And to promise this every week for eight weeks and then deliver? That, my friends, that is a gift. That is a very nice present that they have given us.

I’ll return the favor by doing my part, and geeking out.

So I’m not saying that there is a secret story that can only be seen by those who have been to film school. True Detective is a movie like Full Metal Jacket, where the symbolic meta-story pretty much tells the same story as the regular story. Think of it as music with great lyrics, an awesome bass line, and a wailing guitar solo, and you’ve just about got it. Yeah, classically-trained guitarists might get more out of the second solo to Layla, the slow one with the slide, but that doesn’t mean we can’t all enjoy the song.

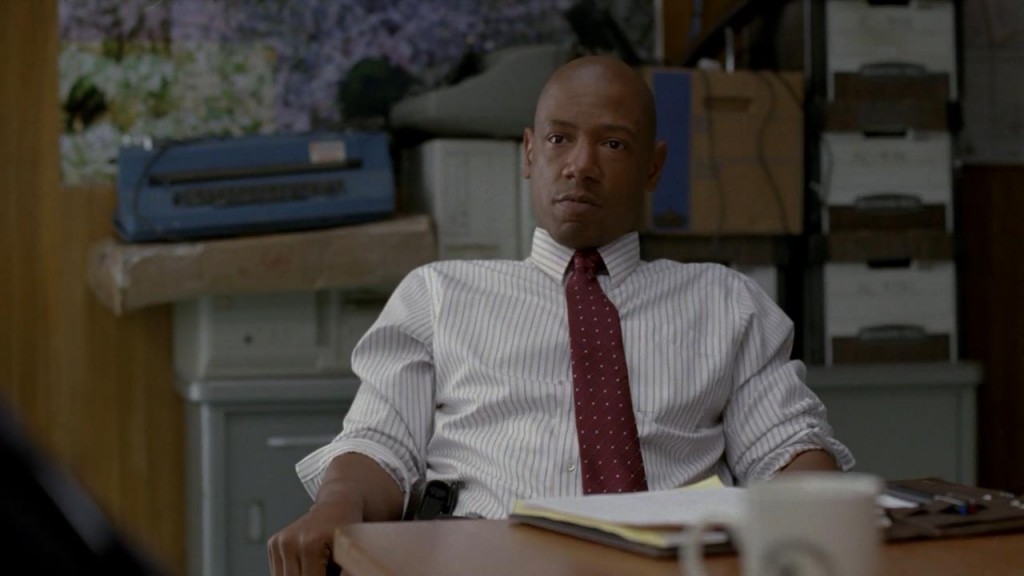

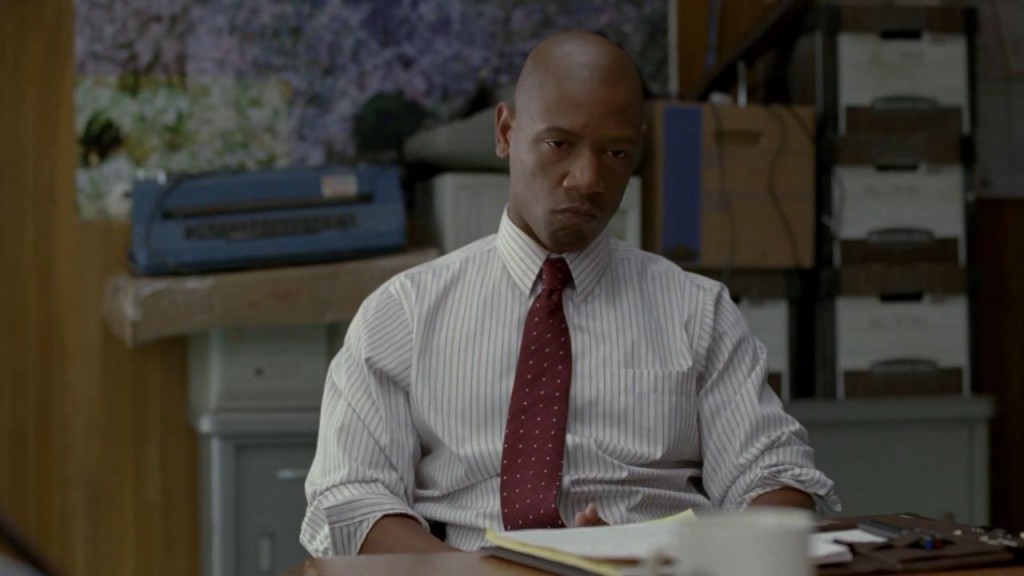

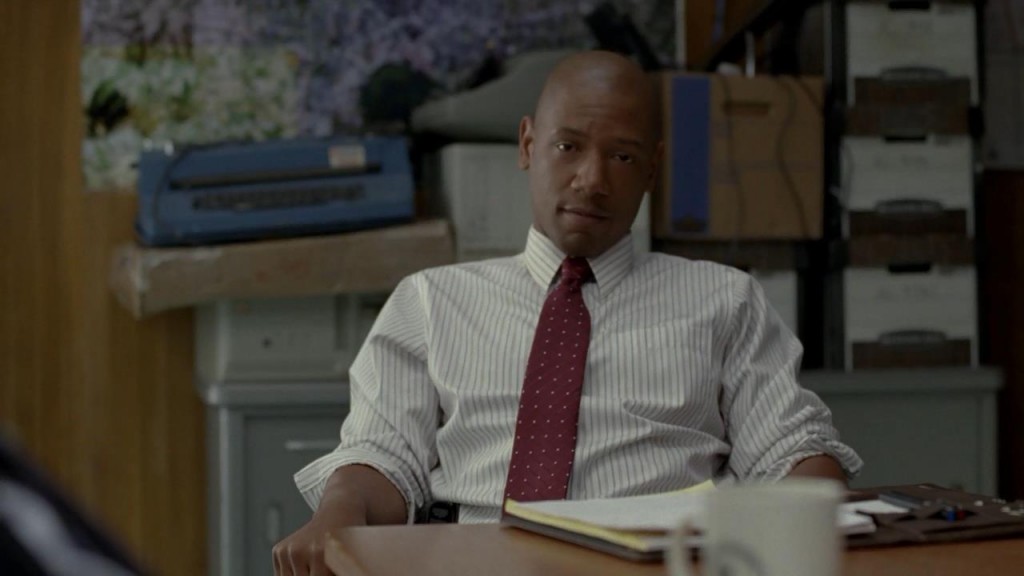

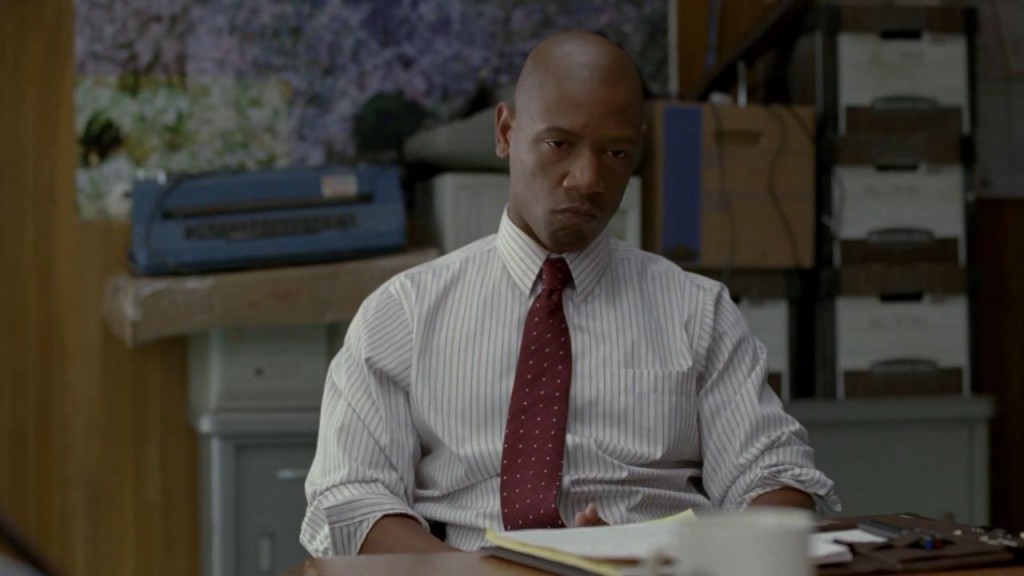

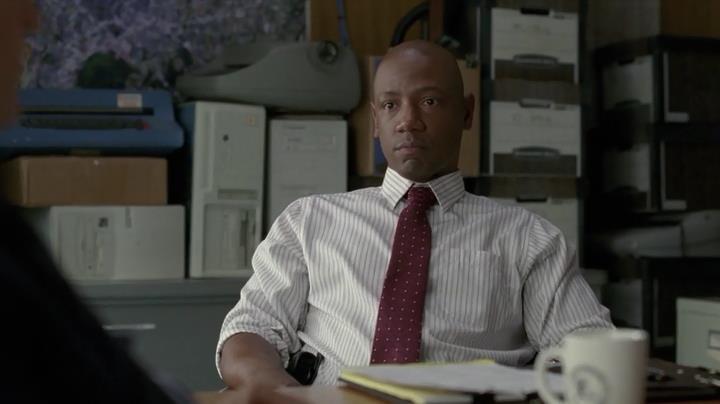

One thing I’d been noticing is this lavender patterned map that appears behind Detective Papania whenever Marty says something stupid.

I mean, obviously the map is always there, but there are only certain shots and angles where they show it. It’s very precise indeed.

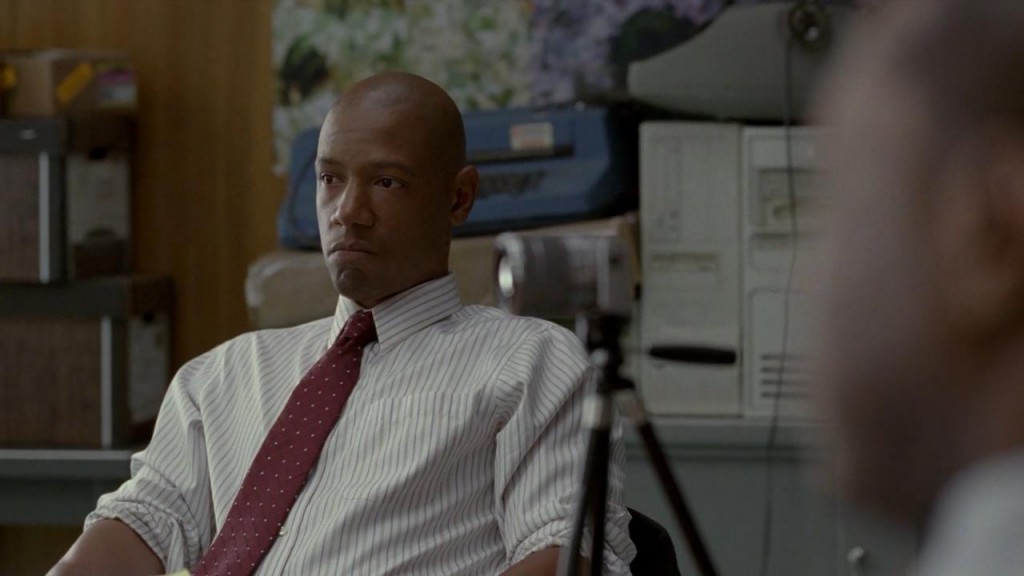

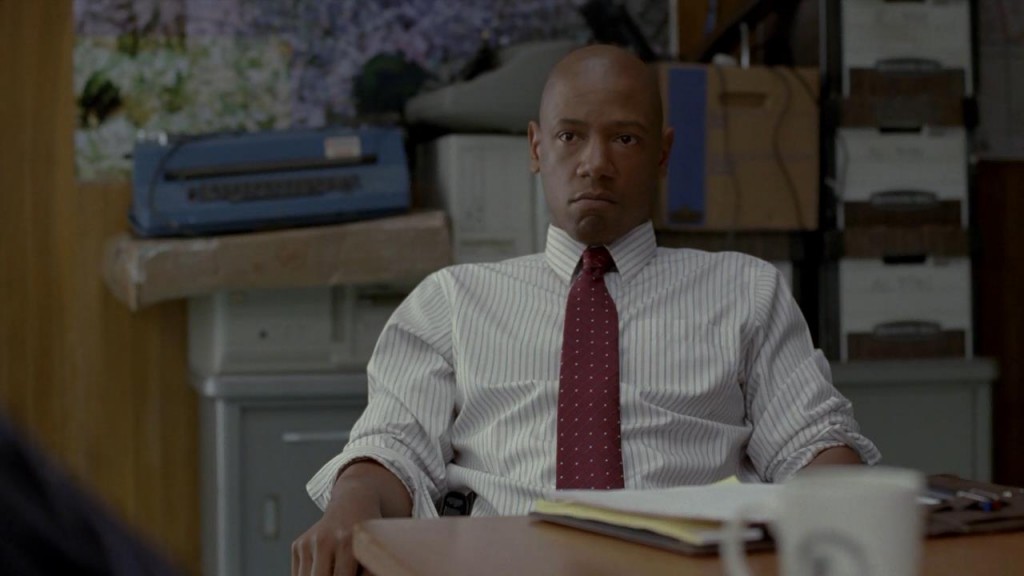

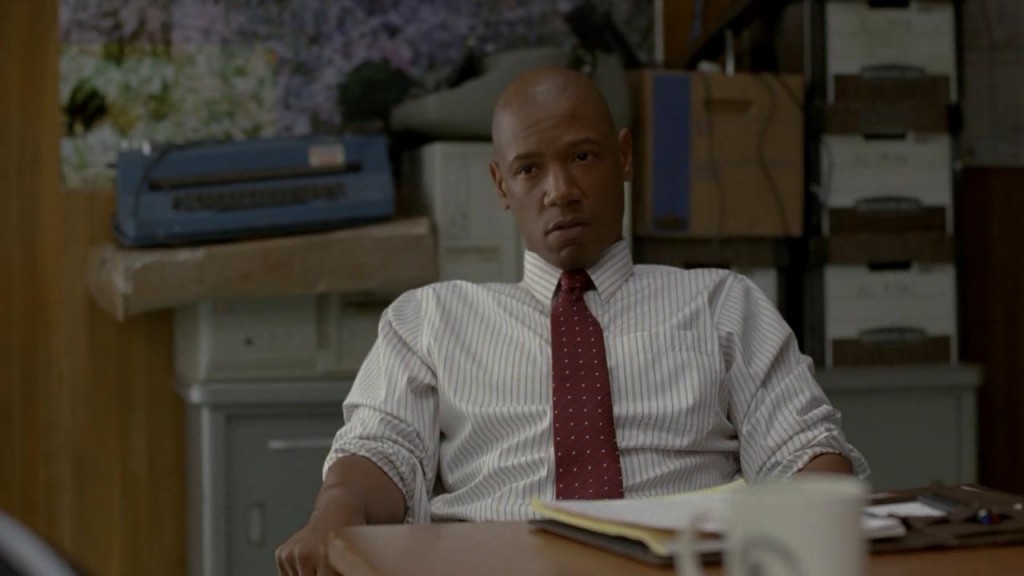

Here’s where I display my True Scholarship, because I went through the whole show and screencapped every single time that map appears behind Papania (the younger detective). Here they are, along with what they were talking about when it happened:

After Hart asks them what’s going on with Cohle Papania says, “It’s alright, we just heard some stories.”

Hart: “My dad, I had about six inches on him, and even in the end I still think he could’ve taken me.”

Listening to Hart say, “You know what I mean…you gotta decompress before you can go being a family man.”

In response to Hart asking if they want to hear about the raid on LeDoux’s, Papania says, “Eventually, sure. Right now we’re just trying to track the case.”

Notice Marty starts to intrude on the shot.

That’s the last time you see the map in Marty’s interrogation. The next time you see it is towards the end of Cohle’s interrogation, when Papania and Gilbough decide to reveal to him that he is their suspect.

Episode 6 (the last interrogation episode, in which it becomes clear that they think Cohle is the killer) has some interesting stuff to say about this purple map.

Back in 2002:

This scene sent me down a rabbit hole of speculation. No, that’s not the same map as in the room. But it’s close enough, close enough that they would have had to have tried to get a map that was similar but not the same, and it’s not there in 1995 or 2012. Remember that this is the first time that we see the 2002 storyline. Also notice the orange-suited invisible man in the shot — I’ll have more to say on that subject soon. But this here is the frame that really tied something together for me:

I started looking through this particular combination of Papania and map with no clear idea what I was going to find, but I’ve noticed certain themes recur, over and over again, with that map. And with this frame four major story elements that I’m finding over and over again with this map appear:

1. Black cops versus white cops.

2. Taking people for granted.

3. Overlooking something important.

4. Hurting people’s feelings by accident.

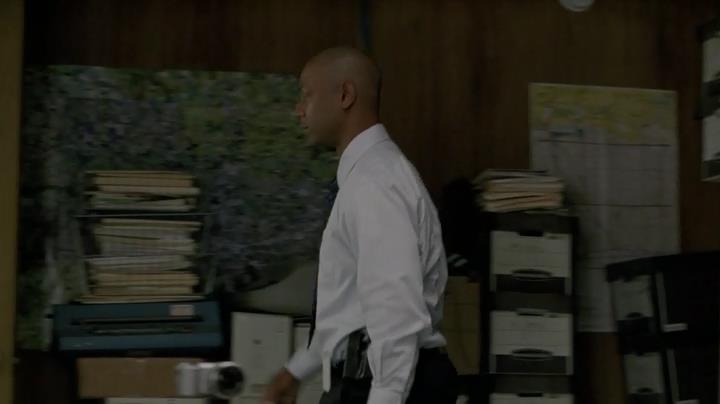

Let’s get one thing absolutely out of the way. That map is not on the wall there in 1995 or 2012 — it’s there now, in the 2002 set. It’s only in this shot, the 2002 station only appears this one time and that wall only appears in this particular single set-up. That actor, who is nowhere else in the series and the only black actor in this scene, has been instructed specifically by the director to go walk in front of that map, stand there long enough for them to deliver one line, and then leave.

That map is not the same map on the wall in the interrogation room, but it is so close as to be indistinguishable — they had to find a map that was almost but not the same. This is not an accident. That map is part of a visual motif, and an important one.

Let’s proceed without the endless arguments of whether or not set designers put things on walls on purpose. Of course they do. That’s their job that they get paid to do.

This is not a sign of a long-ranging conspiracy or anything within the story. This is the background reacting to the foreground. The map appears — which is to say, the set is dressed and the shot is framed so that the map appears — when the person driving the action in that particular exchange is overlooking something important because and losing essential detail in the pattern. That map was not put there by the Illuminati.

I’m sorry, and I’ll tell you, if you made a TV show where that map was put there by the Illuminati I would watch the hell out it. But it hasn’t happened yet and it is not this show.

Now’s a good time to mention, once again, how closely that map resembles a floral pattern.

(and by the way, the next scene after Marty and Rust fight over the report is the one at the mental hospital, where the flowers from Marty’s bedroom appear on the hospital wall)

Last scene in the police station, last scene in 2002, the interrogations are over, the map does not appear again.

SO WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?

Well, let’s review. Scroll back up to the top and look through the screencaps again. Remember that I’m not claiming any privileged knowledge here, I’m only watching the show, just like you. I’ll remind you of one thing, though; there are a million shots of Papania in that interrogation room, and the map is there for all of them. These are the only times that it appears. I have exhaustively sorted through the whole series to save you the time. If I missed one, send it over and I’ll add it in, but I don’t think I missed one.

I think the fact that the files and boxes are stacked over the map in Maggie’s scene symbolizes how completely she is a dead end in their investigation.

I think the fact that the map does not appear in Rust’s interrogation in any meaningful sense (it’s even darkened when they walk by it) is because Rust does not take these men for granted. These men do not blend into the background at all. They are his students, and his adversaries.

Rust never says anything even vaguely racist, as opposed to Marty, who is a big one for saying casually racially insensitive things and then rolling his eyes when someone gets annoyed:

It’s hard to say whether certain lines were filmed a certain way or if he happened to sit a certain way when saying certain lines or what….it all combines together into the story as we see it, and what we know is that when a character appears in front of a floral background the detective in question is not really seeing them. And a lot of them know it. Here’s the scene that made me start to suspect what was going on:

Marty: “My dad, I had about six inches on him, and even in the end I still think he could’ve taken me.”

Why is he so pissed?

Because, issues of fatherhood and legacy loom in this character. And, for some reason, hearing this old white man measure penis size against his father, who was probably even more racist than he is, really seems to annoy Detective Papania.

Legacy

One of the major themes of this show, and I’m not at all certain it’s in the script by the way, is legacy.

Let’s look at this show as an expression of the monster-slaying myth.

This here is a generally excellent essay that expresses a really good point:

Marty is Ariadne, Rust is Theseus, Childress is the Monster, and Carcosa is the Laybrinth.

It’s close enough that it works, and it may even be on purpose. After all, it’s been on the radar since House of Leaves, why wouldn’t they take the next step here? Maybe it’s just a general blueprint for monster-fighting.

So Cohle is Theseus entering into the labyrinth to slay the monster, Hart is Ariadne who provides the clues to get in* and the path back out again**.

*While watching the show for these essays I’m struck again and again by how tenuous the thread of leads they follow is. They get precisely one clue per scene, and it’s always at great effort. Don’t hold me to this observation yet, but I’m pretty sure that if you had subtracted even one of their sordid Louisiana interactions they would not have been able to Solve The Case. This makes sense and is a fairly easy way to write, because they’re telling the story backwards and recounting the exact trail of clues that led them to Carcosa.

**After slaying The Monster Rust says, “We didn’t get them all.” “No,” says Marty, “But we got ours.” And with that he lays a path back out of the Labyrinth. Rust can escape. Check that essay I just linked to as a good extrapolation along these lines.

The point of the Minotaur myth — of any myth — is that it happens, over and over again, amongst all aspects and all realities. Time is a flat circle or something, sure, I guess, but with that knowledge comes the need to train replacements, because everything’s gonna happen again. There are monster-slayers who came before these two, and those who will come after. It will be Papania and Gilbough’s turn next in the long line of honored pictures on the storeroom wall.

One of the cool little mini-meta-stories of True Detective is the way that the police department evolved. You can see this in the commander, going from screaming Captain Quesada in 1995 to Captain Lou Shoutydude in 2002 to their old buddy as the new Captain in 2012. Another major point they make is that there are a lot more black cops. In 1995 there are no black cops, just a lot of pasty white guys like Steve Geraci. In 2002 you start to see black cops appearing, as I demonstrated, out of the background.

2002: As Rust leaves the station for his appointment with the reality of flowers he walks around the black cop who had been standing in front of the map.

And now in 2012 the new detectives are on the block, and Marty and Rust take the trouble to school them.

Papania and Gilbough are both younger than the men they’re interviewing, though Gilbough is the older of the two. Gilbough is quieter, more inscrutable, apparently deeper. If one of them is into the occult it’s him, he’s the box man, he’s the mystic. I try to avoid looking for cute name references, but Gilbough’s name is close enough to “Golden Bough” that that’s how I remember how to the spell it. Papania’s name, I don’t know exactly what it means. It has the word Papa in it. I know that he has three kids, that he’s still married to his first wife, and that he appears to have father issues.

He doesn’t like Marty’s casual racism, and Marty’s casual racism is highlighted several times. I know somebody can tell you say exactly what kind of racist Marty is, but I’m not qualified. I just know that he’s this one particular type that I’ve met a few times. The “regular guy” type….he’s not actively racist, but he has a lot of weird little racist tics and he doesn’t think a thing about it. Check out the scene where he returns in 2012 to talk to the new captain:

Hart: “A pilot, you racist bastard. What else would you call them?”

The official non-racist joke of racists.

This joke’s told over an establishing shot of the new office, in which you see a black guy working as he tells it. True Detective is making a point here. Cops in 1995 were casually racist. 2012 cops are a lot less racist, and a lot more sensitive about it, and Marty’s out of place and out of time. Things are changing. The black detectives have emerged from the background, and resent being overlooked — being forced back into the background. Like Marty resents being forced into the background.

And all these floral patterns in the show? Maybe they represent the people that the detectives see as background, as simple flowers on the path of their life, to pick or cut down as they choose.

When Rust goes to visit the girl in the hospital, that’s when the flowers snap into full focus. Here, for the first time, Rust confronts the consequences of his action and inaction, attention and inattention. The girl he saved? It turns out that he never saved her, not really. She’s not okay. She never got the help she needed.

The people in floral patterns in this show….this is a good time to remember something. This show is from the point of view of the characters, or Hollywood, whichever you prefer. The point is that everything is prettier, handsomer, more dramatic, clearer. This is a movie that is very much from the point of view of the main characters, and that means it is they who clothe these people in floral patterns. It’s Marty who thinks his daughters match the wallpaper. His daughters most certainly do not agree.

There are a lot of people in this show who blend into the background (try to find a shot in the office in 1995 that doesn’t have an orange-suited prisoner doing menial work somewhere in the back). All this talk of flowers in the series, all the pictures, I think this is what it’s about. Flowers are inanimate objects. Flowers are there to look pretty. They don’t think anything, they just grow. They are indistinguishable from each other, they simply each grow according to their nature. Some people seem like flowers to them. But the flowers hate them, because the flowers are really people.

When the Monster makes love to his sister, he “makes flowers on her.”

That’s pretty deep, right? That seems like a pretty brilliant comment on the mentality of highly focused alpha males to me.

How do people think of this stuff? How does anyone come up with little tiny background stories like this, to enhance and illustrate the foreground so brilliantly. And that’s why there’s the strange and jarring touch of the children’s flower drawing suddenly writ large.

If this stuff is not really in the film, if this is just my imagination, then I am so dang proud of my imagination. And if it’s not really “there,” then it’s like I made it up, isn’t it? So you won’t mind if I use it in my own work.

And when you see it in my work, you can be sure that I am actually doing it on purpose.

This is part four of a six-part series about True Detective.

Here are the other five-and-a-half chapters:

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Six-and-a-half

![TD s01 (5).mp4_snapshot_47.32_[2014.04.19_04.55.40]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-5.mp4_snapshot_47.32_2014.04.19_04.55.40.jpg)

![TD s01 (6).mp4_snapshot_52.31_[2014.04.22_20.57.08]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-6.mp4_snapshot_52.31_2014.04.22_20.57.08.jpg)

![TD s01 (6).mp4_snapshot_36.47_[2014.02.26_02.17.27]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-6.mp4_snapshot_36.47_2014.02.26_02.17.27.jpg)

Thanks for reading and linking to my essay! Your writing on True Detective has been fun to read too, especially the more cinematic perspective you bring to it. This show really inspires some hard core fandom.

You really nailed it with Theseus and Ariadne. I assume you read House of Leaves?

It’s interesting that Daedalus and Icarus are the flip side of that myth.