This is part six of a six-part series about True Detective. Here is the entire essay.

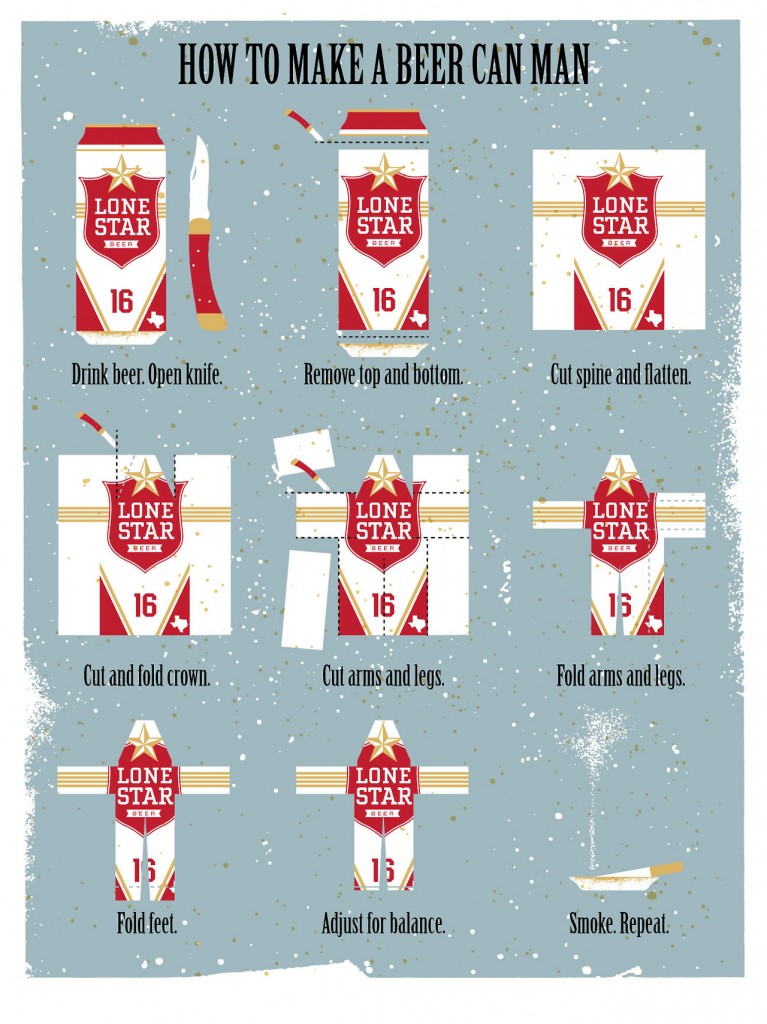

The point of this essay is not that They Are Doing This, it is that WE SHOULD BE DOING THIS. I draw comic books. It’s easier than making movies. I don’t need to find a couch with a picture of a duck on it, buy it, drag it to the set, light it just right — I can just draw a picture of a couch, and then on that couch I can draw a smaller picture of a duck. IT COULD NOT BE EASIER. All I have to do is to be able to think of it.

Now that I’m aware that backgrounds are repeated very few times (in an eight hour show you rarely have even three shots of any given angle, and usually not nowhere near that many) and that we have nearly infinite forgiveness for what’s in a background (I’m on a patio outside a coffee shop as I write this, and if you photographed me from the left you would have a completely different background than from the right, yet they are all the same scene and the human mind has no problem accepting it) I am going to explore more with my backgrounds. It’s not just about creating depth; I think I’ve learned that trick. The background has no choice but to comment on the foreground, and since the backgrounds do not often repeat I may as well use them to their fullest potential and let them react directly to the action in the foreground. True Detective does that constantly, and BOY does it work.

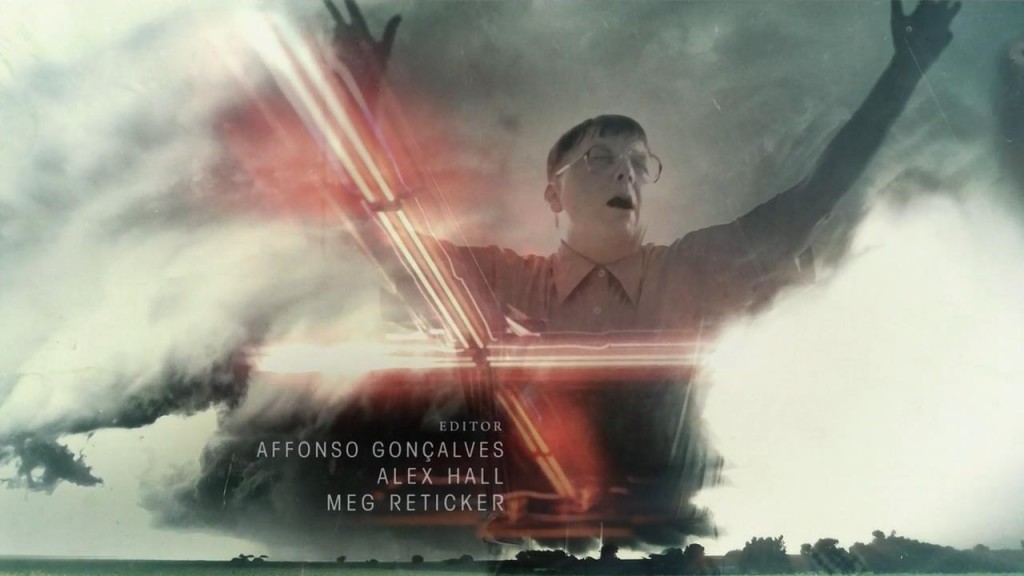

I would like to wrap this essay up and get back to my true purpose in life, which is stealing ideas from this show and using them in my own comics. I can think of no better way to do so than to examine the most oft-repeated imagery in the show: the opening credits.

The opening credits comprise a visual lexicon of images underpinning the entire work, some more obscurely than others. Think about it — this is a film made by intensely visual people, and these are the images that they want you to consider every single time you watch their show. It’s more than just a fancy way of showing you Woody Harrelson’s name. You already know Woody Harrelson’s name.

The way this interweaves with the music is quite nice, and at least two points it gives important information. Watch it once or twice or at least listen to the song:

Ready?

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.08_[2014.04.29_18.35.16]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.08_2014.04.29_18.35.16-1024x576.jpg)

Start with Rust, brooding holy-ghostlike over all Louisiana. Louisiana is played here by a refinery and a lot of grass and an overgrown old road.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.09_[2014.04.29_18.35.08]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.09_2014.04.29_18.35.08-1024x576.jpg)

Introducing the most important concept in the series: women. Note the tiny doomed house in front of the enormous chemical plant. The home, juxtaposed with the refinery.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.13_[2014.04.29_18.35.53]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.13_2014.04.29_18.35.53-1024x576.jpg)

A woman, a refinery from above; an abstract view.

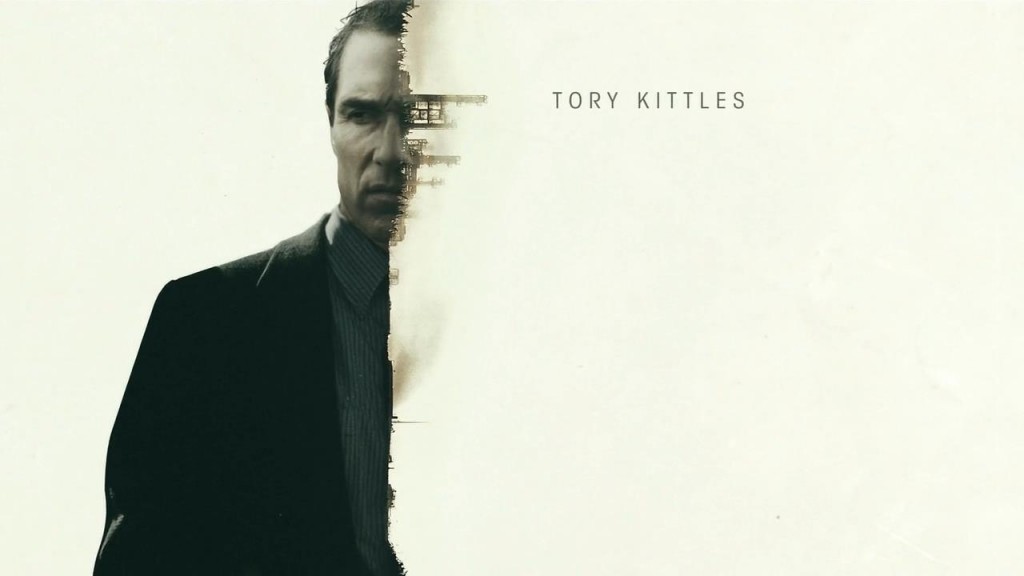

I’m going to be honest; I’m pretty sure that’s Matthew McConaughey but I’m not completely positive. Anyway, this introduces the “half-finished man” image which turns up a lot in the opening credits.

Note strange cartographic element delineating the left edge of the face — it looks like a drawing of a river.

observe: bird. So this is another half-finished man, but Rust has a bird in him somewhere.

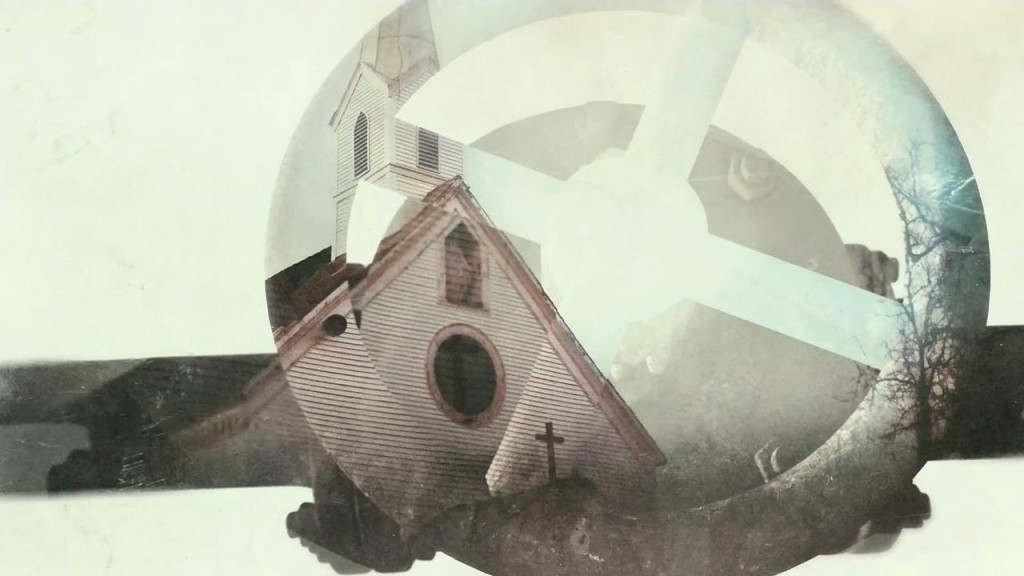

So that’s sort of interesting — a church superimposed on a cross-shaped gear. Religion as machinery — this fits in with the refinery imagery; this is a show where things are separated into component elements, isolated and intensified.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.29_[2014.04.29_18.36.54]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.29_2014.04.29_18.36.54-1024x576.jpg)

And here we see the creosote, I suppose. Creosote being both a kind of tree and a kind of chemical byproduct. The tree growing out of the house into the chemical storage tank is a sort of visual poetry that Fukunaga does very, very well. Most people try like the dickens to avoid having a tree grow out of a character’s head or a tree come out of the middle of a house. Fukunaga rushes to embrace it, and it works.

I suppose this is important, because that guy is prominently featured in e02 and he seems to be twining his spines up slowly. The neon cross in the sky is nice.

Maggie, looking worried.

I’m pretty sure that’s the CGI jellyfish from the recent James Bond movie, Skyfall, when they’re fighting in front of the billboard. Or maybe all jellyfish look the same.

This shot and the next four shots set up some sort of sequence or mini-story; watch close.

This is the “flowers” shot, and it absolutely does not appear in the show (unless you count Audrey’s drawings, and that looks more like eggs than flowers to me. It’s difficult to say what’s up with her arms and costume, but she’s clearly a woman, sexualized but not particularly attractive, and I’d bet that she represents Errol’s sister.

Another mysterious shot that does not really appear in the series. Let’s follow it in:

They all have the same mudflaps. But in all other ways they are as different as semi trucks can be. What does it mean? You tell me. Maybe it’s saying that the men at the truck stop are all the same.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.46_[2014.04.29_18.37.56]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.46_2014.04.29_18.37.56-1024x576.jpg)

That’s a parking lot projected on her back. Combining that with the antler imagery, I’d say that whatever happened to this grey girl was none too pleasant.

Following that sequence through, I think it shows that Maggie is worried about nature, that someone will make flowers on her daughter, which will cause them to end up working at a truckstop, where their shoes will hurt and men will objectify them and treat them as animals or as parking spaces.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.48_[2014.04.29_18.38.02]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.48_2014.04.29_18.38.02-1024x576.jpg)

and maybe Marty should be worried too, but he’s a half-finished man with a stripper dressed in the American flag dancing in his mind. She shows up in the series; she’s part of the all-important scene where Marty tracks down Tyrone Weems and it just so happens he meets his creator.

Marty gets juxtaposed with American flags a lot, by the way. And in his last scene with Papania, in which he “passes the crown” of True Detective to the younger man, they both get lots of American flags.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.50_[2014.04.29_18.38.09]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.50_2014.04.29_18.38.09-1024x576.jpg)

If this image wasn’t gorgeous I would say it’s out of place, but the music is such an important part of what’s going on anyway that it works. This moment is all guitar, which I sort of like. It’s a way of saying, the way this guy strums a guitar is so interesting that we can spend four measures on it. Why not make it part of the imagery? Especially when strong straight lines are such an essential element.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.52_[2014.04.29_18.38.13]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.52_2014.04.29_18.38.13-1024x576.jpg)

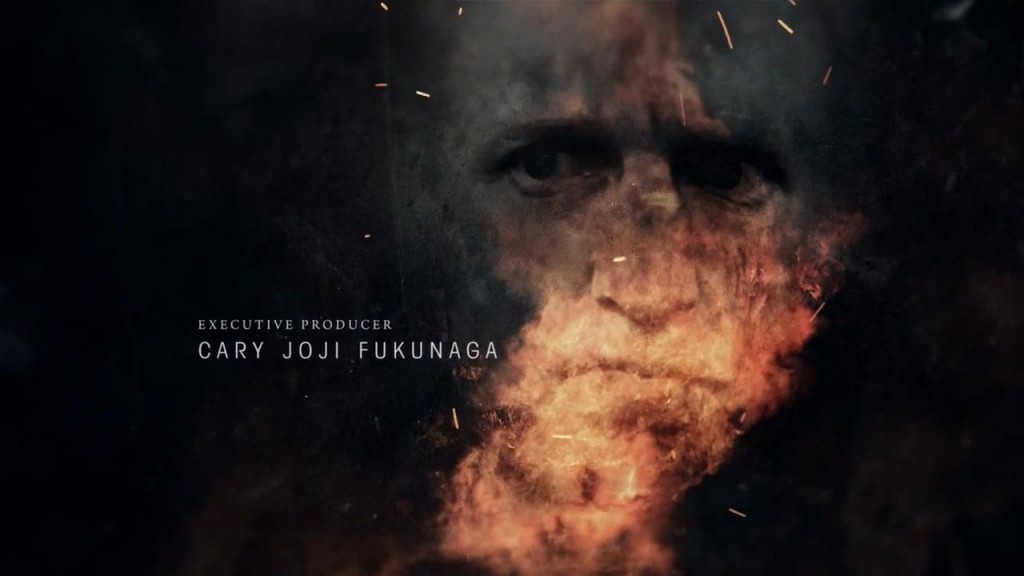

Note the guy is bald like a monk. What they’re trying to say here is that Rust is cold and lonely.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_01.55_[2014.04.29_18.46.22]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_01.55_2014.04.29_18.46.22-1024x576.jpg)

Refinery on his right, the cross on Calvary marooned in midair above him, a church to his left. Rust is in an attitude of prayer. Rust is a very religious type of atheist. This is a different type of atheist from me and most of the atheists I know; we just don’t give a shit, and find the whole topic of conversation boring. Not Rust. He’s the type of atheist who keeps a cross over his bed. Seems a bit evangelical to me, but what the hell, it’s TV.

That traffic circle occurs in the series; that’s Rust’s truck (and also IRL the director’s) driving up his chin, this is the moment just before Rust sees the tracers I think.

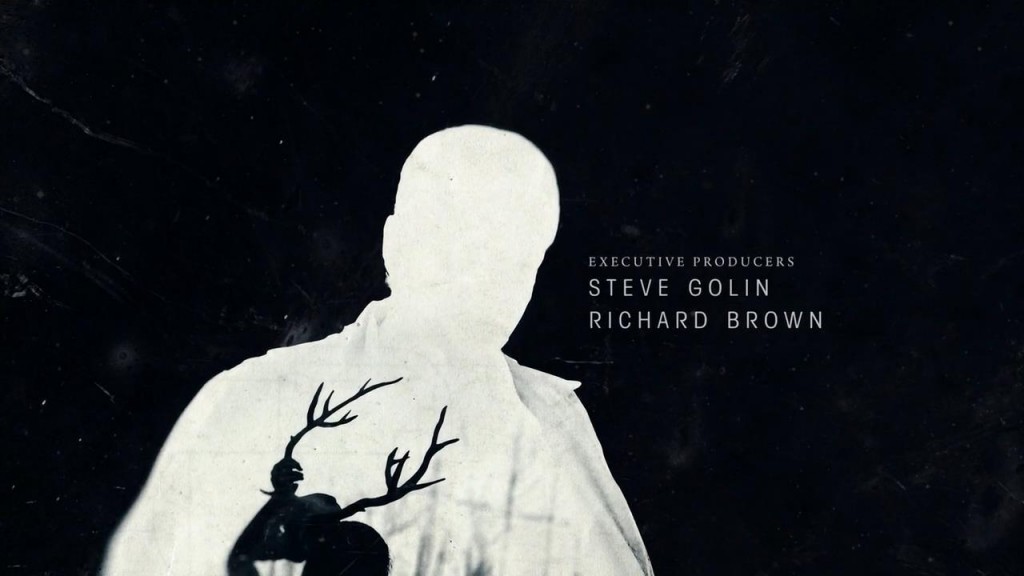

I’m not sure who that is; it could be Marty or anybody. I guess they’re saying that some mysterious man is hiding a desire to be a wild thing. They’re actually rubbing a skull on their face, not just the antlers. Then it bursts into flame.

It is extremely significant that the female voice enters at this moment.

This is one of the moments that made me sit up and say, alright, this show is commenting on sexism directly.

It’s a woman’s butt, on which is projected a playground. Alright, alright HBO, I get it. But this isn’t just an HBO series, but a critique of HBO series. So it’s a particularly lonely and abandoned playground, and the woman’s voice that sounds so maternal and soothing is saying something quite grim.

They’re calling her and she is not answering. The number is 2207, which of course is LOSS spelled upside down.

Note where it says “lone.” Rust is the burning remainder of a man abandoned by women, being refined and purified, bone-dead.

Next there are four very fast images, snapping by in time with the snare. You are meant to respond to these without really seeing them.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_02.12_[2014.04.29_18.47.17]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_02.12_2014.04.29_18.47.17-1024x576.jpg)

That’s Audrey. Weird internet controversies aside, doesn’t matter who the model is, that’s Audrey. Refinery below.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_02.12_[2014.04.29_18.47.27]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_02.12_2014.04.29_18.47.27-1024x576.jpg)

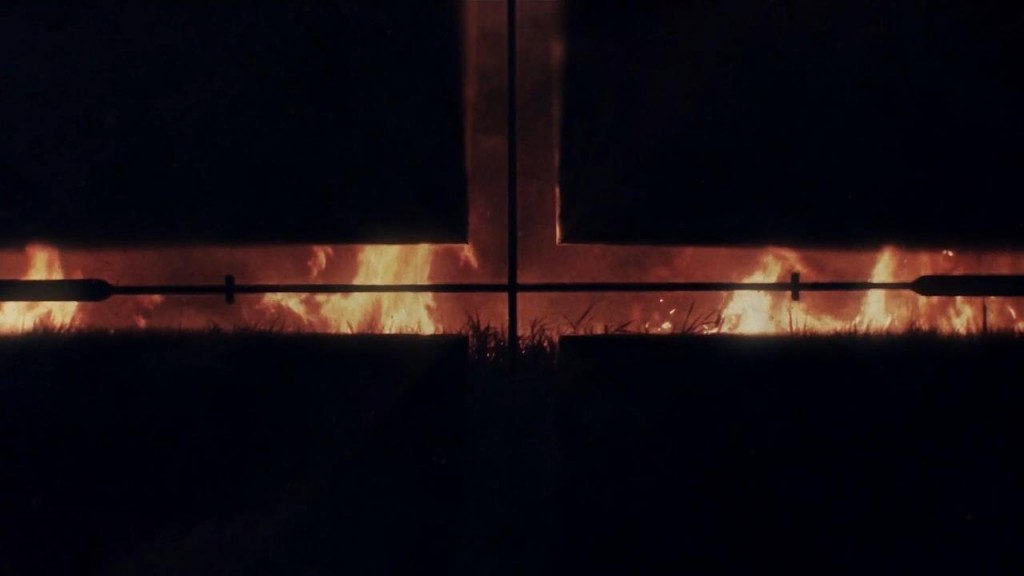

Crosshairs join cross and refinery.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_02.13_[2014.04.29_18.47.38]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_02.13_2014.04.29_18.47.38-1024x576.jpg)

Refinery turns to fire and antlers appear under the crosshairs.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_02.12_[2014.04.29_18.47.33]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_02.12_2014.04.29_18.47.33-1024x576.jpg)

That’s probably Dora’s tree behind them, or close enough. The credits are saying Audrey’s the next Dora Lange, which is definitely carried out by the series. There isn’t a conspiracy that’s got Audrey as the next target, not a conscious conspiracy at least. It’s more that the patriarchy has her in their crosshairs, and that Christianity and tradition are refining her into an animal that they can hunt.

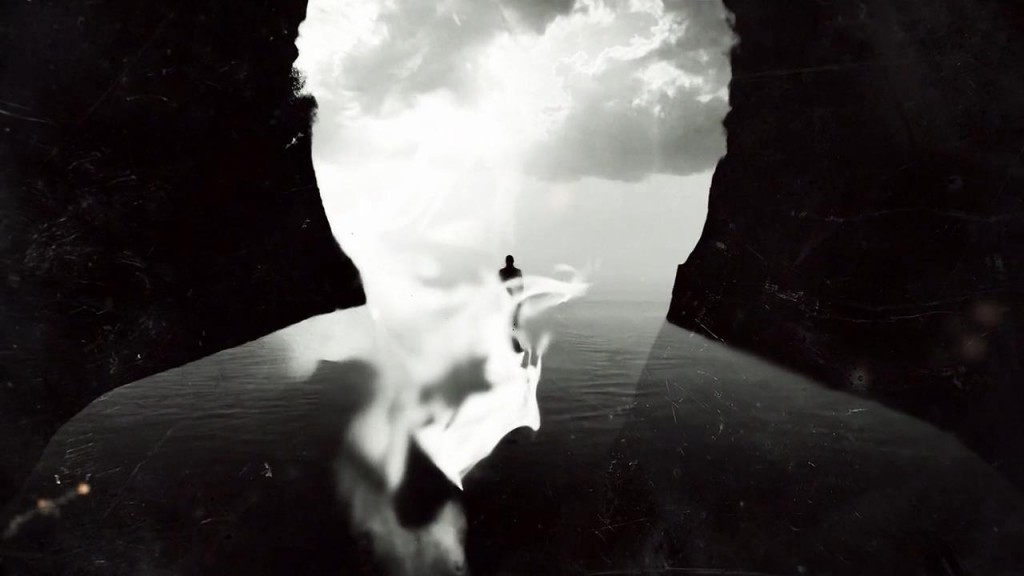

I think this is interesting because at the end of the credits, after the Trouble With Audrey, we begin to revisit the imagery from the beginning of the credits, but reversed and oddly changed. This, of course, is exactly what happens in the series. After Audrey’s trouble in 2002 the investigation revisits so many characters that they met before, but with important changes every time (and this is where the explanation for the Steve Geraci story comes from, by the way).

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_02.17_[2014.04.29_18.47.50]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_02.17_2014.04.29_18.47.50-1024x576.jpg)

Bodies, tangled in the crosshairs, overlaid with the same ring intersection from before. There aren’t a lot of details, but after watching the show you have to wonder if this is less sexy than a picture of the boy and girl from the LeDoux hideout. Whatever’s going on here is not necessarily good.

This one isn’t hard to figure out. Marty’s house blew up. Marty looks worried.

The flame begins to touch the wintery man inside Rust and lo, the frost begins to melt.

Rust is burning, but at peace. The antlers recall the flames.

zooming in, crosshairs on the burning cane field from the first scene in the first episode. Through flames and antlers Rust will turn the crosshairs away from women and onto the evidence of crimes. And he will become:

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_02.32_[2014.04.29_18.48.37]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_02.32_2014.04.29_18.48.37-1024x576.jpg)

As I mentioned in part two, this is part of the series, and it’s the part where they stop to piss and check their directions. Men voiding themselves on film; this is a fair description of True Detective. There may be more to it, but that is undeniably what is going on. If you watch the video you’ll see that Rust makes a slow but significant movement with his hand; pulling something out of his jacket, I guess.

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_02.35_[2014.04.29_18.49.03]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_02.35_2014.04.29_18.49.03-1024x576.jpg)

Marty is looking around, Rust is there with his book or maybe a map. Beyond them, the refinery. Apt.

The song is so good for this that I just can’t say. Leave alone the excellent southwestern flavor of the music, the words are just perfect. The lyrics begin with a literal objectification of a woman, and after the female voice joins the narrator dies and becomes objectified himself. Yep, that about sums it up.

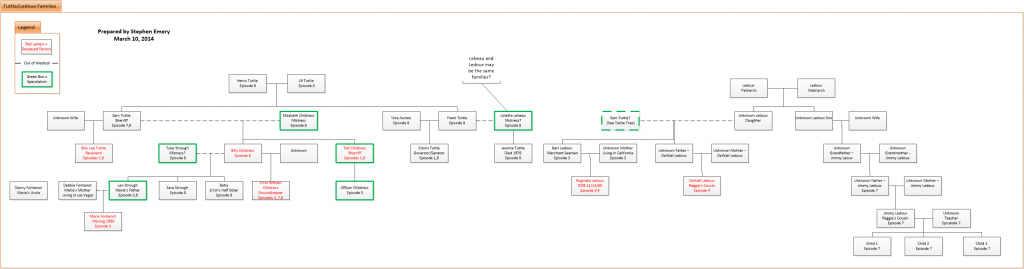

Here is the original storyboard for the opening credits. Compare and contrast, if you so choose.

You’ll find it was pretty much all there from the beginning.

Loose Ends

There are a million things more to say — I never got to castration anxiety (which is everywhere).

I never touched on the role of bullshit and nonsense in the series:

it’s great that you care, and I even see the crossed sticks behind you,

but I’m pretty sure that, in the real world, police do not pick up corpses from crime scenes and carry them off.

What about the conspiracy? Surely it would be great fun to decipher the conspiracy.

And I barely even mentioned the acting at all, which is such a major oversight that it probably represents the fundamental flaw that stopped me from being a good filmmaker.

I’ve written almost 30,000 words on True Detective and barely mentioned the actors once. That’s because they do such a seamless job of inhabiting their characters that I could just pretend they were real people, and that’s a great way to do analysis; but it suffers from one major problem; it’s just not true. All I can really say to that is two things:

“Oh well.”

and

“Maybe next time.”

But What Does It All Mean?

I love movies. I love TV when TV is big movies. I went to film school and I always wanted to make movies; still do, though any movie I ever get made now will probably start as a comic book so I concentrate my efforts there. I also love good film criticism. This article about the Shining is one of the most interesting things I’ve ever read in my life, and I’ve always wanted to write something like it. I don’t think I got close, but that’s okay. He’s dealing with a movie with actual hidden meanings. I’m writing about a TV show that really, really means what it says.

Marty meets Nic Pizzolatto, the writer of True Detective.

The dancer with the outrageously terrible breast implant surgery behind him is probably not an accident.

I’m not going to lie to you — I identify with Nick Pizzolatto. He’s exactly the same age as I am, he used to live in Austin too, and we seem to share the same taste in books and people. I’d like to think, if I had stayed in California in 2009 and started going up to LA to work, I’d be in a similar position to him now, working as a writer on the moving pictures and doing okay at it.

But I’m not going to pretend that what I would have written, if I had done that, would have been as good as True Detective. I don’t think I was capable of writing something nearly as good until I’d seen this show. This was the missing puzzle piece for me, the spark that lit the fire in the vast piles of dried timber around my mind. I always knew that telling stories was important — now I know why it’s important. I can see that stories are made of bits and pieces, and I can arrange them as I choose and tell different stories in different ways.

I can’t do anything else until I finish this essay, and that’s the very best place to be as a creator. I have a clear artistic task that I know, deep in my soul, that I must finish before I can return to my other projects. But I also know that this exhaustive review of a TV show is not the loftiest of pursuits, nor is it going to make a huge difference to anyone but me, so I have to do it as quickly and professionally as possible. Like I said, that’s pretty much the best place to possibly be as an artist. I’m also utilizing the only really good trick I know as an artist. Allow me to digress here.

Why is it that we listen to punk music and classical music? Same person (in this case me, but this applies to everyone) goes straight from Shostakovitch to Bikini Kill, maybe swings through Stax Records or Camper Van Beethoven on the way (all these roads meet in the mind of Spencer Krug, but that’s another story).

What is it that makes Operation Ivy (three chords churned out by high school students in the mid-80s) the equal of Beethoven? Because they literally are. They have equal weight in my playlist and I bet you there are more people listening to punk right this second than classical. This is in spite of the fact that classical is undoubtedly “better” and preferring punk is a little bit like personally spitting in the face of every single person who ever studied music in school.

My theory is that it is the learning we are after. We pick the art forms that suit us, based on our personal history and personal relationship to culture and personal personality. But what makes “good” work are two things.

The first is flawless virtuosity. We love to see people go through the paces perfectly. We love to have our expectations perfectly fulfilled. This explains the blues — people have been playing the exact same song in the exact same way for a hundred years, and the blues musicians that people like are the ones who make it look easy.

The second is “learning on the bandstand.” We can detect, and we adore, that delightful flightful gravity-free feeling of making the connections, of seeing the pieces drop into place, of learning. It’s infective and addictive. We love it. We love to watch the moment that the story leaps out of the hands of the creator, twists into a living thing. It is my theory that those moments are somehow enshrined in the work, the song, the film; we can SENSE them. The experience of watching another learn is intoxicating to us. We long for true exploration, for truly new territory to be broken. This is why jazz improvisation is so thrilling — because (in theory) we’re watching them learn. They aren’t repeating themselves. They’re saying something new.

I made a point of not exhaustively planning this essay before I wrote it and not waiting until it was done to publish it. I wanted the thrill of learning as I wrote, and I wanted the people who read it to have that thrill too. Maybe I’ve hit that point a couple times in this; there are things about this essay that I like, things that I will do better the next time I write an essay like this. I wanted to share things like the thrill of watching the meaning of Papania’s map fall into place, which I literally figured out while writing the essay.

I feel that I’ve displayed less virtuosity than improvisation in the writing of this essay, but you ain’t exactly payin’ me so I don’t mind workin’ mostly to please myself.

True Detective displays both qualities in spades, by the way. The virtuosity displayed by the show is staggering — do you know how good at making movies you have to be to pull off things like having gradually more black detectives from 1995 to 2012? Or how totally amazing it is to see somebody reference Chambers and Lovecraft but NOT the Cthulhu Mythos? But the act of learning is everywhere. Fukunaga and Pizzolatto and a lot of other people took many personal strides forward in the writing of this show, and it shows. You can really see all the experience points on the screen.

Now, I believe that once you reach a certain point of smart, all very intelligent people are more or less equally intelligent but in different directions. I don’t want to say Pizzolatto is smarter than anybody and I sure don’t want to say he’s smarter than me. I don’t want to say that, because it’s a very limiting statement, and I want to get out there now that this enormous essay is done and prove that I can do this too, and I don’t want to think I have the imaginary ghost of a guy who’s actually a lot like me looking over my shoulder as I do my comic book thing. That’s a mental trap that I don’t care for.

But on the subject of story, this guy is ahead of me. He has used his 38 years on this earth in a different way than I have, and his studies into story and myth are absolutely deeper than mine. I think the thing I overlooked is philosophy. I seem to have a pile of old dime novels in my mind at least as high as Pizzolatto’s, and I flatter myself by saying that my storytelling in my comics is clear and understandable. But philosophy says something that I’ve never been able to find by adding up history texts and science fiction novels. Philosophy studies why stories exist, what stories are made of, what stories are used for. Philosophy is the aeons-old attempt to find functioning and reproducible myths. Reading novels and histories only told me what stories had already been projected on the wall of Plato’s cave. I could see the wall of the cave, the shadow, and the cavemen. But philosophy examines the fire directly, and that was what I was missing.

Pizzolatto has my eternal gratitude for showing me this. I needed a work of fiction that pointed me back to philosophy, that let me know this is important.

And as soon as I get done with these three books on the Civil War and this crime novel from France I’m gonna read some philosophy. I’m going to read it for real this time.

I’m not jealous of Pizzolatto, nor do I second-guess my choice in 2009. Instead of staying in Southern California I followed my heart back to Austin and the Gathering, and I found love and a home and the most beautiful daughter that I’ve ever seen. I’m happier and healthier today than I’ve ever been; I have no complaints. But now this show has come along, at the perfect moment for me, and it has shown me the way. The path is clear; I know how to keep telling stories, I know why to keep telling stories, I know why telling stories works and I can see the way they are made. I feel like a mechanic who just took a master class in car repair. I am ready to use what I’ve learned.

Thanks for reading, everybody. Essay’s over. Back to work!

Here are the other five-and-a-half chapters:

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six-and-a-half

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_02.29_[2014.04.29_18.48.32]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_02.29_2014.04.29_18.48.32-1024x576.jpg)

absolutely fucking wonderful. I adored every piece of this, and am grateful to both you for writing it and to reddit for pointing it out to me. your insights are effective and welcoming, shamelessly peeling the skin off the show while also drawing the map for coming up with our own conclusions as readers/viewers of this Thing.

I applaud you sir, and will be checking out the rest of your site too.

May I applaud you ability to deliver compliments, sir! That is by far the nicest thing that anyone’s said about the essays so far. Thanks so much; you make it all worth while.