True Detective: The Ending of Something in a World Where Nothing Ever Ends.

on April 22, 2014 at 1104This is part three of a six-part series about True Detective. Here is the entire essay.

The ending suffers from one simple drawback: it’s not the best episode. The fourth episode is the best episode. The fourth episode is a peak TV experience and if every episode of this show was as good as the fourth episode then everybody could retire and we could all go home and just watch True Detective season one over and over again. There would be no need for season two. But they have yet to perfect the art of television, and episode eight is not as mysteriously magnificent as episode four. Oh well, sorry.

But the last episode does have plenty to offer, so pay attention. It doesn’t end with a grand resolution and it tells you that it’s not gonna near a million times before it gets there.

The story closes with some tantalizing clues to the mystery behind the mystery, a fascinating dissertation on consensual hallucination and the meaning behind Carcosa, the resolution to the buddy detective show that we’ve been watching this whole time, and then a sparse and human moment in which a lonely man makes peace with the spirit of his dead child. It’s not really the ending; it’s just the last episode.

No less a luminary than Scott Snyder, some guy who writes Batman, wonders why Marty did not experience the supernatural element (singular) of the last episode. He wonders why poor Marty didn’t get even one CGI for his own.

True Detective is a show that plays by the rules. It’s genre entertainment, and it delivers that genre precisely. Now, it’s genre with something extra, and that’s why we love it. But the buddy-cop-versus-serial-killer story thumps through it all regardless, and it is delivered upon with no subversion or subterfuge.

It’s obviously a purposeful choice, and I believe a principled one. Unlike wink-and-nod satires like Starship Troopers and Full Metal Jacket that allow people to have their fun action movie and feel superior to their fun action movie at the same time, True Detective plays it perfectly straight. It doesn’t subvert the genre at the end to prove that it’s smarter than the genre. Nothing “supernatural” happens to Marty because Marty simply isn’t in that type of movie. Marty’s the straight cop in a buddy cop movie that’s bigger than he can understand. If Marty participates in CGI shenanigans at the end of things then you’re not watching a film noir with a metaphysical commentary track, you’re watching an exquisite episode of the X-Files.

Marty is sheltered.

Part of the game here is that everything is real. The King In Yellow appears not just as a name, but as a concept.

The King In Yellow

In 1895 Robert Chambers wrote a book about a play, and in that book people who went to see this play went mad. Lovecraft picked up this thread in the 1920s made references to the King in Yellow in his books, adding the character to his pantheon (from which the King in Yellow eventually came to be known as a Dungeons & Dragons monster, but our examination stops short of there).

The writer of True Detective, and this is the point that has opened my mind to a new dimension of storytelling and won my eternal respect, picked up the concept of the King In Yellow and put it into his story as clearly and cleanly as you would put a new carburetor in your car. He even uses the concept three different ways, to make sure you get that he’s doing it on purpose. It’s stylish, I’ll give him that. It’s one of the more impressive feats of literary wizardry I’ve ever….I don’t want to say “seen.” I’m sure there’s stuff this clever going on in a lot of great stuff. But it might be one of the greatest feats I’ve ever been aware of.

So the story uses the symbol of the character of the King in Yellow, as if they were a real person, a King, wearing yellow clothes.

They use the King in Yellow in the cosmic, Lovecraftian sense, as Hastur, the monster beyond space and time.

And they use the King in Yellow in the Chambersian sense, as a symbol of madness and a play that drives men mad. And that raises the interesting question.

We know what a guy in yellow looks like.

We know what scary monsters from beyond space and time look like.

But what kind of play could drive men mad?

What kind of thing could you watch that would permanently damage your sanity?

True Detective answers that question: a videotape of some extremely terrible things happening to a young child. Everyone who watches it feels furious and sick inside. It is a cursed object:

So the Play That Drives Men Mad is brought to life as A Real Thing in this show. By plugging those two concepts together, even if everything else about the show was discounted, Pizzolatto would have earned the undying respect of weird fiction aficionados. We’ve been asking ourselves for decades, “What kind of Play Could Drive Men Mad?” and he answered our question. The answer had been pretty obvious all along, but at last somebody got around to saying it, and once we heard it out loud we knew it was the truth.

There is nothing Lovecraftian about this at all, except for all the things we associate with Lovecraft but don’t think of as Lovecraft. This show doesn’t use his invisible sky fiends — it assimilates and appropriates his story style. That’s a wonderful trick. Like I said, I find this inspirational.

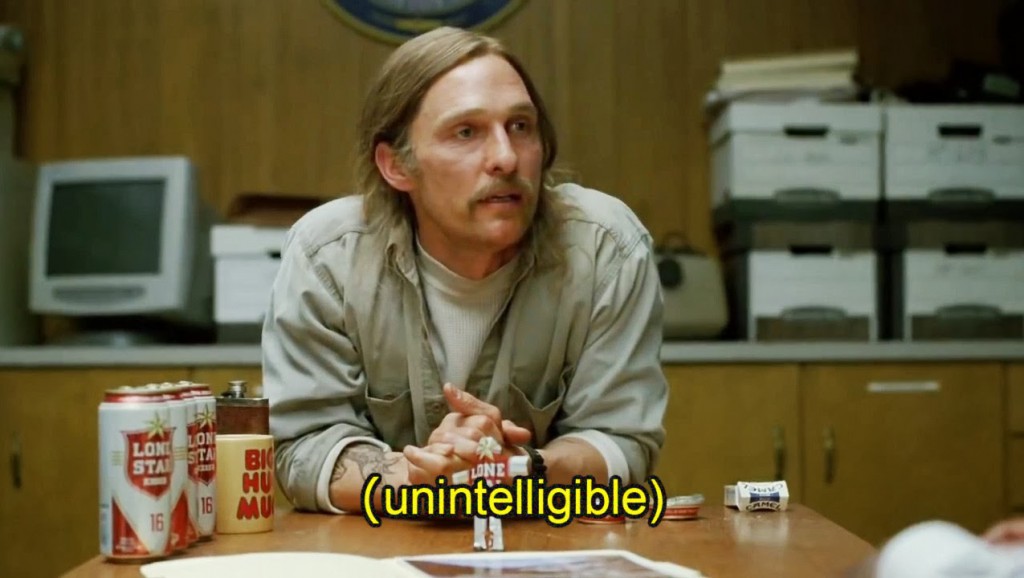

What is Rust Cohle but the Lovecraftian narrator come to life? He sits down with his pad of paper, or in this case with his interview room with two witnesses and a camera, and he slowly goes mad. He starts making little dolls out of beer cans.

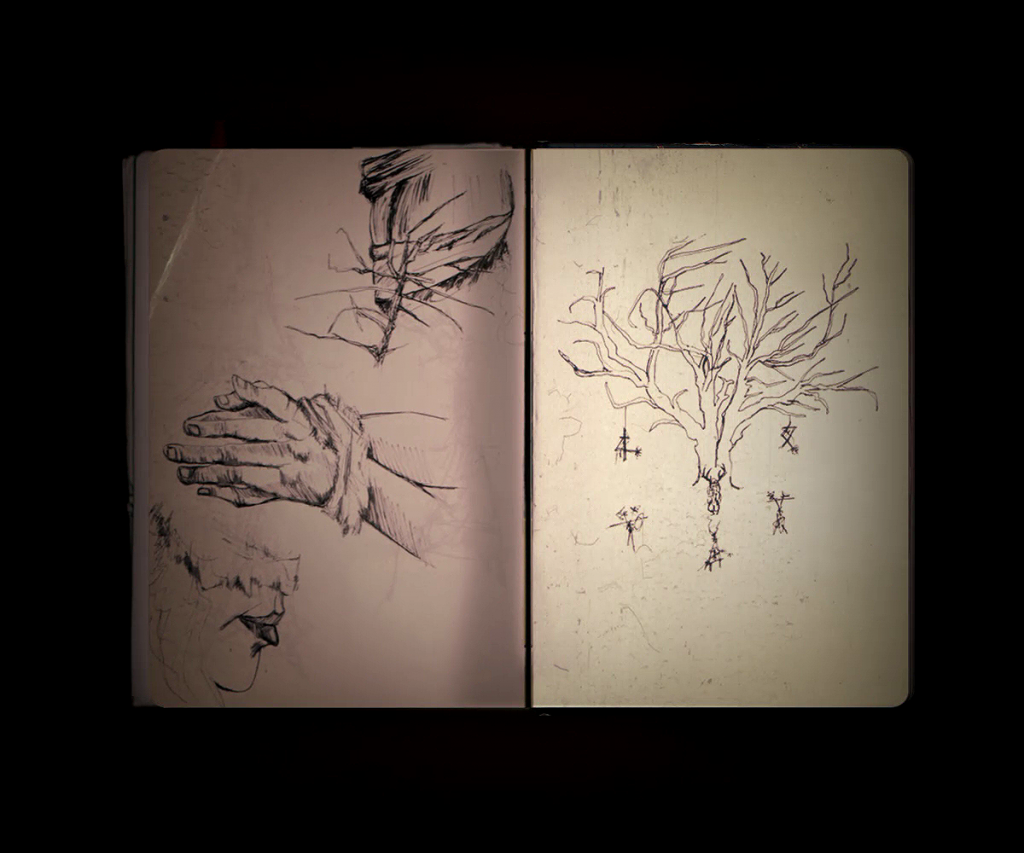

I’m not sure what that means besides the symbolic, by the way. There’s a repeated motif of five men standing around one woman:

Basically the only reason to not decipher this as some sort of gang rape analogy is that it maps perfectly to Marty, Rust, and the troopers at the crime scene.

The five beer can men around the one flat can. Rust gets it. Curiously, the five/one beer can sculpture is shown in blurry form along the bottom of the screen several times, but it’s only shown completely in this, the very last shot in the interview room.

I don’t know what it means but it does not spell good news for the woman. There are those who say Rust was doing that as a coded message to the interviewer’s bosses, so they would know he was on to them. Yyyyyyyyyeah maybe. That does make some sense. The show almost casually provides men in high places to be behind these terrible crimes, and the rigid dramatic rules of the show, where every move stands for something else, imply strongly that Senator Tuttle would be brought down by these revelations.

But Rust goes reliably mad, as he tells the tale of the Dora Lange investigation, he descends into cosmic horror and vague ranting, much like this article itself. It always happens that as you go deeper and deeper into the truth behind the truth the farther it takes you from other human shores. That’s why we try to build these bridges.

It’s not supposed to be easy.

Carcosa

I haven’t been through the whole True Detective reading list yet; I’ve yet to read Ligotti, or Schopenhauer, or anywhere near enough Bierce. I’ve read pretty much all of Lovecraft and most of the King in Yellow by Chambers.

I’m positive there’s a lot about Ambrose Bierce in this. Bierce was a veteran of the Civil War who spent a lifetime exorcising his bad dreams by pouring them into American literature. He’s mostly known for An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, the story that created the “the main character was dead the whole time!” plot point that you’ve seen so many times in [SPOILERS] and [OTHER SPOILERS], but Bierce is a pretty significant writer who wrote a lot of stuff way back a long time ago. He’s one of the founders of what would become weird fiction, then pulp fiction (where True Detective determinedly plants its roots), then horror novels and horror movies and modern horror. They’re going way back in the family tree for this show, to the root of American horror, in the American War.

It’s very interesting that the taproot goes exactly back that far and no further. There are several times in True Detective that it is implied that the “conspiracy” or the “problem” goes back to the Civil War, especially when Carcosa is revealed to be an abandoned Civil War fort. Curiously, the fort is not in the script, but it is in the final product, so it totally counts. Though Pizzolatto is the originator of this story, he’s far from the only progenitor. The color and background stuff that I’m about to get into is obviously not the product of the author, but it is essential to the story. To put it another way, he may write the song but it’s the band that plays it.

Bierce created Carcosa in this very short short story: An Inhabitant of Carcosa. It’s basically a tone poem about not much besides death, ruin, and decay. There’s not a plot, just a collection of images portrayed as a sequence of events. It’s curiously reminiscent of the poem that Howard first wrote about Conan, which is also a blank story about mist and little else.

After a hundred and fifty years, what eventually emerges from this mist is the shape of the show that we just watched. That’s an interesting process.

Bierce anchors us to the Civil War, when Carcosa was obviously the poisoned aftermath of the War Between the States. Then Carcosa became something else with Chambers, then something else again with Lovecraft, and now with True Detective all those meanings are simultaneously extracted and meshed.

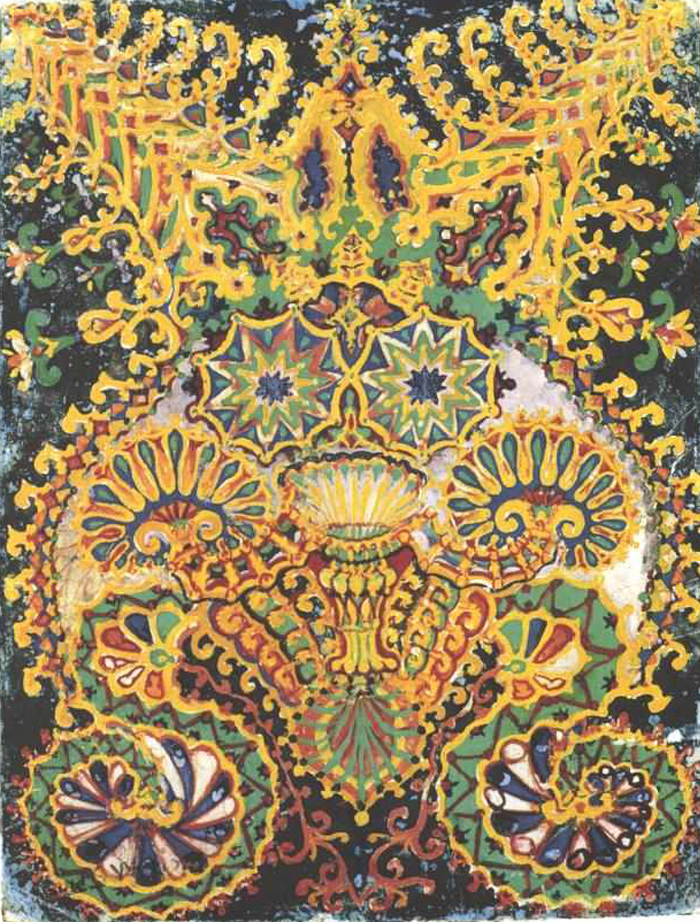

Nowadays Carcosa sounds like “carcinogenic,” which may be the point of oil refineries in the background everywhere and the “twin suns rising over the lake” at the end of episode 3:

Along the shore the cloud waves break,

The twin suns sink behind the lake,

The shadows lengthen

In Carcosa

By the way, there’s an oil refinery back behind that low rise.

“An owl on the branch of a decayed tree hooted dismally and was answered by another in the distance. Looking upward, I saw through a sudden rift in the clouds Aldebaran and the Hyades! In all this there was a hint of night — the lynx, the man with the torch, the owl. Yet I saw — I saw even the stars in absence of the darkness. I saw, but was apparently not seen nor heard. Under what awful spell did I exist?

I seated myself at the root of a great tree, seriously to consider what it were best to do. That I was mad I could no longer doubt, yet recognized a ground of doubt in the conviction.” — Bierce

I’ve yet to read Kierkegaard, and it’s only the influence of something as good as True Detective that could make me even want to. I’ve never been one to study philosophy. So, for this next part I have to lean on a different internet commentator called The Last Psychiatrist, whose article on True Detective contains some useful hints. TLP doesn’t really get TD either, but they were in conversation with yet a third internet commentator, who goes by the unlikely name of Pastabagel, and it is that which I excerpt here:

According to Kierkegaard, this resignation to the eternal is crucial. Kierkegaard was not an atheist but a diehard Christian. He believed that when a man resigns himself to the eternal, to existing in eternity, and gives up everything that ties him to this world then he becomes a “knight of faith” capable of great Christian acts (like the self-sacrifice that is almost certainly coming in ep. 8). When Kierkegaard wrote about a Knight of Faith, he contrasted the Knight of Faith to the mere Knight of Infinite, the “God botherer”–a phrase used twice in the show. What did Kierkegaard say the Knight of Faith looked like? Like this:

Why, he looks like a tax-collector!” However, it is the man after all. I draw closer to him, watching his least movements to see whether there might not be visible a little heterogeneous fractional telegraphic message from the infinite, a glance, a look, a gesture, a note of sadness, a smile, which betrayed the infinite in its heterogeneity with the finite. No! I examine his figure from tip to toe to see if there might not be a cranny through which the infinite was peeping. No! He is solid through and through. His tread? It is vigorous, belonging entirely to finiteness; no smartly dressed townsman who walks out to Fresberg on a Sunday afternoon treads the ground more firmly, he belongs entirely to the world, no Philistine more so. One can discover nothing of that aloof and superior nature whereby one recognizes the knight of the infinite. He takes delight in everything, and whenever one sees him taking part in a particular pleasure, he does it with the persistence which is the mark of the earthly man whose soul is absorbed in such things. He tends to his work. So when one looks at him one might suppose that he was a clerk who had lost his soul in an intricate system of book-keeping, so precise is he.

Back to True Detective. TLP pointed out that Pastabagel nailed it that Pizzolatto was taking Kierkegaard and bringing it to life. This may even be true.

It’s certainly intriguing that Rust is known as “The Taxman” and finds Childress by….searching tax records. It seem to me to be a fairly well informed conjecture that Pizzolatto was trying to bring the Knight of Faith to life, which makes it all the more interesting that Rust has a pronounced limp.

This ties into the most explicit “literary” allusion I’ve found yet. Erroll Childress is obviously the ultimate God Botherer — really, he bothers everybody, but in the final confrontation in Carcosa, as he has Rust spitted on the point of his knife (and what kind of knife? I’m sure if I knew it would contain some important detail), he said, “Take off your mask.”

This is of course a terrible mistake, because in a world where the ideas behind the King In Yellow are real there is only one response:

From Robert Chambers’ “The King in Yellow”

Camilla: You, sir, should unmask.

Stranger: Indeed?

Cassilda: Indeed it’s time. We have all laid aside disguise but you.

Stranger: I wear no mask.

Camilla: (Terrified, aside to Cassilda.) No mask? No mask!

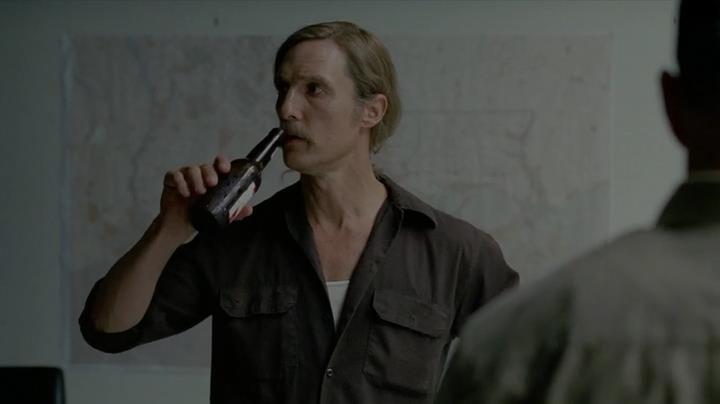

Rust wears no mask. He is in the world, and of the world. He lives a life unsheltered. Errol wears nothing but masks. Every time you see him he looks different, talks different, acts different. He is a powerful but shattered mind. Rust, on the other hand, knows exactly who he is.

So he wins. And he wins like he usually wins; by using his head. In this case he uses it to head-butt Childress a bunch of times, but it still counts. Rust’s the Big Head, Marty’s the Little Head. Even here we are in symbolism.

Shelter and Logic

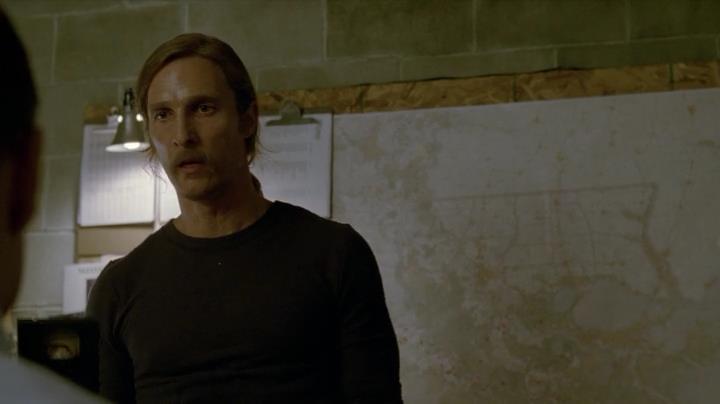

Note cross hanging above Marty, straight line dangling above Rust.

This sets up something important, deep, clever, and eminently doable. One of the main things I’m looking for in this analysis is stuff that is possible. Some things can be done, some things can’t. I’m interested in the story that springs de novo from this document, yes, absolutely, that’s my favorite part. I love to see the machine run.

But I’m also a technician, and I have a technician’s interest in the show. What is it that they did — that they could do — with their show to gets the story across in another way?

Well, here’s one thing. The show sounds like it’s dismissive of religion as “two sticks crossed together” but the show does not actually agree with itself on this question. Religion is depicted as arbitrary and inane but still helpful and useful. The bird traps are a demented form of the narratives that we us to get through our lives. The comforting shelter of narrative is fundamentally wrong but still fundamentally quite nice. It’s strange.

So the show’s an atheist’s show, sure, but it’s a critique of atheism too. If the show is fundamentally on the side of anything, it is on the side of doubt.

The shelter of religion, family life, social life, all the little lies are often depicted as a triangle.

The brute linear nature of logic and true perception of cosmic horror is depicted as a straight line.

“Translation of fear and loathing to an authoritarian vessel; that’s catharsis. He absorbs their dread with his narrative. Because of this he is effective in proportion to the amount of certainty he can project.”

Why yes it is, Rust. That is exactly what this show does.

This is not impossible to do! Let’s say you’re making a movie about two people who have a lot of quasi-religious conversations and you want to add a visual layer to the dialogue. You don’t need CGI to make this happen; all you need is a couple tent poles.

Marty is sheltered. He’s inside the structure/trap/framework depicted by religion, of which the bird traps are a primitive, debased echo.

It’s interesting that the show connects evil and debauchery to nature, barbarism, primitivism so often. These men that they chase are evil precisely because they continue to carry out their debased rituals thousands of years after they should have ceased, in a modern world that has no place for them.

And it’s also interesting that the revival church is depicted as a fairly positive place. I thought it was sinister that so many of their symbols appear throughout the story, but it turns out that it’s just the sort of story where symbols are everywhere and the preacher is one of the smartest, best people in the show. Why those nice young gentlemen even help their car get out of the mud they’re stuck in.

And later in the episode Rust meets Marty (with his red Volvo family station wagon)

Later, in 2012, Marty has his moment of brutal self-honesty in his office:

Strangely, at this moment, for the first time in the show Rust gets to dream a little bit.

Logic says there is no shelter, not really. Shelter doesn’t care, because it’s nicer inside.

The bird traps are of course the same thing:

There’s nothing wrong with this! There’s definitely something wrong with cults sacrificing children, but stacking sticks together in an attempt to make life more bearable is entirely a laudable pursuit.

“I always thought it was something for children to do. Keep them busy. Tell them stories while they’re tying sticks together.”

Childress, Carcosa and the Yellow King

Childress is the perfect serial killer. I mean, the dude has it all.

Dolls with broken faces.

Creepy pictures of his grandmother, inbred girlfriend/sister cooking breakfast for him.

Later they have gross old/ugly/fat/incest sex, which I’m sure Western society can agree is practically the worst sex.Also, notice that practically everything in the background is doubled.

He even has this awesome lair.

Oh, that? That’s not his real lair. He has an even cooler lair than that. That’s just the spare lair where he keeps his dad tied to a bed so he can torture him to death (or maybe he’s already dead, but based on the fact that you can see a pulse on him while Dora Lange looks really, really dead implies that this show will give you a corpse when they want you to see a corpse).

THIS is his awesome serial killer lair:

I’m sure you’ll agree that in depth and breadth this guy is the champion murder-monster of all mankind. Errol Childress, inbred spawn of a Southern Gothic Murder Family/cousin of a Very Powerful Politician, is all serial killers at once. He even has an awesome serial killer theme he whistles as he searches for his (young, defenseless) prey.

Some commentators have pointed out, and I’ve yet to thoroughly prove it myself but it checks out so far, that Childress is the only person called a “monster” in the story. This is in spite of the fact that the story is chock full child-rapist televangelists, methheads who kill babies, cops who cover up terrible crimes, biker gangster home-invaders, and inbred cousins who cook meth and LSD apparently out of orphans. They all qualify as monsters, but only Childress gets the title. He’s the Monster. He gets to wear the scary mask.

So Childress is the most imaginary of all imaginary monsters. He does it all. He’s a loner, he’s a cult, he’s a nobody, he’s related to the Governor, he preys on children, he fights adults with a tomahawk, he follows a code known only to himself, but he kills his dog with zero hesitation.

Childress is more Hannibal Lecter than Buffalo Bill, as Thomas Harris would be the first to point out. He’s not a real person, but an amalgamation of things we have seen in scary movies. For Rust Cohle’s Big Case he gets to fight the Encyclopedia of Serial Killers, and if Childress made a bird trap for every person he killed he’s one of the most prolific monsters since Dracula. There are many crazies in the world but he is not one of them, he is a creature directly from the imagination. Unlike the traditional meth lab/sex slave operation of the LeDoux compound, this thing has scope and range. He is the end of all serial killers, and the writer writes him like he never plans to write another one so he wants to get it all done this one time.

I respect that.

I hope you follow what I’m saying about symbolism here. I’m not saying that they’re using symbolic language to tell some impossibly complex story about bad-ass serial killers at a literary frequency that only neckbeards can hear. I’m saying they’re using really simple and universal symbols to make their story far, far more intense than it has any right to be. In lesser hands Erroll Childress would be just another movie monster. He wouldn’t be scary, he wouldn’t be deep, he wouldn’t make you think about life. He’d be just another guy who hangs out in a lair and provides entertainment.

But by actually doing their jobs as artists and creators, by actually doing everything they knew how to do and doing it extremely well, the story becomes so intense that it vibrates into the fourth dimension. This may well spell the end of a genre, because True Detective may have been The Serial Killer Movie To End All Serial Killer Movies. There are two basic types of genius HBO TV shows; those that look back, and those that look forward. Those that close the door on a ending genre, and those that frantically carve out a new one. You can call them “Sopranos” and “Deadwoods.” This show is probably a “Sopranos.” After this, Se7en clones may seem a little more silly.

But this show may be something more. True Detective appears to be of equivalent depth to the Sopranos, and in far less time.

Of course, the ending of the Sopranos was bette

Here are the other five-and-a-half chapters:

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Six-and-a-half

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_06.42_[2014.04.13_02.19.02]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_06.42_2014.04.13_02.19.02-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (3).mkv_snapshot_16.24_[2014.04.13_02.49.17]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-3.mkv_snapshot_16.24_2014.04.13_02.49.17-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_03.41_[2014.04.14_04.20.53]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_03.41_2014.04.14_04.20.53-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_03.42_[2014.04.14_04.20.55]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_03.42_2014.04.14_04.20.55-1024x576.jpg)

![TD s01 (8).mkv_snapshot_32.37_[2014.04.14_06.04.24]](http://www.unnecessaryg.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TD-s01-8.mkv_snapshot_32.37_2014.04.14_06.04.24-1024x576.jpg)

i love it,,, really a good job.

Thanks so much! I sincerely appreciate it. There’s more to come too, but it’s about time to wrap this thing up.

Excellent work, man. I am really digging this. It ties together a bunch of threads and explains some issues.

Thanks a lot! There’s so much to say that I’ll never possibly be able to get to it all — it really is a very deeply thought-out film.